Reading over the local election results in England, and polls since, one conclusion feels inescapable: Reform UK now has a material chance of being in government in 2029. That marks a colossal shift in Britain’s political landscape.

I want to focus this Substack, though, on policy, not politics1. There, the Westminster chatter around Reform still has serious catching up to do. Commentators are only just starting to leave behind the patterns of thinking they developed when Reform was a protest vote—that could at most shake things up (to admirers) or spew bile (to critics).

Where to next? The conversation, I’d suggest, should move towards asking: what policies does Reform want to implement, and would they be in the national interest? As I put it in last weekend’s edition of The Economist:

“Success means scrutiny. As a protest party, Reform, like earlier Farage ventures, was distinguished mainly by a penchant for scandal and an uncanny ability to nudge the Tories into unforced errors. Now, the notion that Reform could be a party of government no longer seems fanciful. Its ideas should be taken seriously.”

In that spirit, I spent last week going line-by-line through Reform’s 2024 manifesto and some of Nigel Farage’s recent speeches at local election rallies. I didn’t want to get stuck in the mire of litigating immigration, foreign aid or net zero—readers will have their own views there2. Besides, Reform’s stance on those issues is hardly news.

Rather, I focused on the basics of governance: whether the party has a credible economic plan. What I found was pretty alarming.

Specifically, I pulled out every pledge from both the manifesto and recent campaign speeches that had a clear and direct fiscal impact (i.e. raising or lowering spending or taxes). Then, I put together a generous-but-realistic assessment of how much each would cost or raise3. That produces the eyebrow-raising chart below.4

I’d highlight three things:

The numbers are colossal. Look at the tax cuts. The full set that Reform has proposed is something like 3-4x as large as Liz Truss’s mini-budget (though partway-offset with spending cuts).

Much of this has been recently re-affirmed as official Reform party policy. Just under half of these tax cuts, by my reckoning, have been specifically backed by Farage over the past few months. That includes raising the income tax personal allowance to £20,0005 and abolishing inheritance tax6. Some spending cuts have been confirmed too, especially on asylum hotels and foreign aid, but they involve far less money. Reform may eventually move on from its fantasyland 2024 manifesto, but it certainly hasn’t yet.

The sums rely on turbo-austerity to add up, and even then don’t really. Note the large grey bar on the chart: that covers the £50bn or so in “efficiencies” (excluding cuts to foreign aid, net zero, the asylum system, etc.) that Reform wants to find in the British government. That would be an austerity drive comparable to the 2010s, but imposed on a state that is already struggling to provide basic services competently. All that is baked that into these costings; if you assume that Reform loses its nerve over the scale of the cuts, the fiscal picture gets darker yet.

If anyone from Reform would like to send over their own, detailed, alternative to this costing—please do! I’d (genuinely) be interested to look through it.

Implementing this, or anything close to it, would amount to a colossal fiscal shock—and one that Britain, still stumbling out of the shadow of the Truss debacle, can ill afford.

If we extrapolate from Sushil Wadhwani’s back-of-the-envelope breakdown of the impact of Liz Truss’s unfunded tax cuts on the gilt market, this policy package would mechanically raise borrowing costs for the government by something like 150 basis points (1.5 percentage points). Throw in the possibility of a proper loss of faith in Britain’s macroeconomic stability alongside that, and you can easily get to far scarier numbers still.

To be explicit: that would be an unmitigated disaster. Government borrowing would become more expensive, probably semi-permanently. Brits would pay the cost, in higher taxes and shabbier public services. Britain’s current bleak low-growth, high-rates quandary would shift from being an aberration to a norm. I can think of few faster ways to cement national decline.

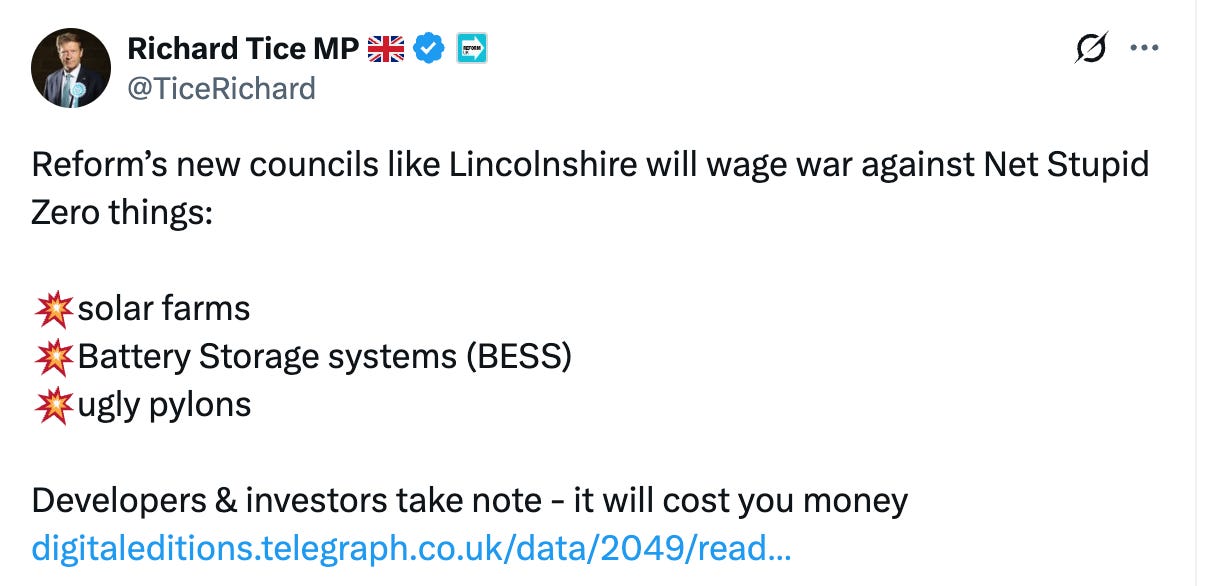

Alongside that, plenty of the rest of Reform’s economic agenda doesn’t have an immediate price tag but is still worrying. A crusade against electricity pylons would ensure energy prices stay high. An ultra-restrictive migration policy7 would jam up labour markets. There are a few better-sounding ideas in the manifesto—a nod to planning reform, for instance—but the overall package doesn’t exactly inspire.

A final troubling habit is a seeming desire to sabotage Labour’s efforts to get growth going today. I have plenty of criticisms of the current government (I aired several after the Spring Statement), but Reform seems committed not just to arguing against the government, but actively making their job harder. Temptation for this sort of destructiveness will only grow as the election gets closer.

If today’s polling holds up into 2028 and there’s a decent chance of a Reform majority, the risk premium any right-thinking investor would demand on any infrastructure project in Britain would surely be vast.

I say that not, or not only, to criticise. Reform has four years to sort this out. They should start soon. There’s nothing inherent in Reform’s core ideas—migration-scepticism, dislike of net zero policies, and so on—that requires them to also drop a fiscal bombshell on Britain. There’s a long transition from protest party to prospective party of government, but Reform also has plenty of time if it gets moving shortly.

An encouraging example, but also a cautionary one, is Giorgia Meloni in Italy. My colleagues wrote a leader on her “not-so-scary” government in January.

“People like labels, and it has always been easy to attach them to Giorgia Meloni, prime minister of Italy since October 2022. She has routinely been dubbed a neo-fascist by her political enemies in Italy and by alarmed liberals across Europe. … But 15 months in, Ms Meloni seems to be conventional rather than a wrecker.”

But one institutional detail may well make a tremendous amount of difference: the Meloni government is a coalition, spanning a range of right-wing parties, including some more moderate outfits, a result of Italy’s proportional-ish electoral system.

Britain, meanwhile, has First Past The Post. The standard argument for FPTP is that parties get few seats unless they hit a ~30% vote share (or are very regionally concentrated). That means they have to appeal to a broad chunk of the country, incentivising coalition-building and moderation. In return, victors get proper majorities and the power to make sweeping changes.

But Britain’s new five-plus party system has broken that logic. The threshold for a majority has fallen, fast, and Reform may well be past it if the latest polls hold8. So far, Reform has made little effort to turn its pile of giveaways into a credible plan for power. That could leave Britain with the worst of all worlds: a FPTP-style unencumbered majority with a PR-style wishlist manifesto. I shudder.

Since my piece for The Economist went out last week, Reform has had the chance to publicly respond. Their efforts haven’t been terribly inspiring either. Zia Yusuf, the Reform chairman, listed a series of past Economist prognostications. Bizarrely, he focuses on a cover about a 2015 market crash in China that very much did happen (and, as anyone invested in Chinese assets over the past decade will be well aware, wasn’t one Chinese markets speedily rebounded from—the CSI 300 is still 25% below its 2015 peak). Needless to say, the Chinese economy also hasn’t grown nine-fold since then.

One Reform candidate tried a similar trick but went back a little further in time to complain about our coverage of the Great Depression.9

Among the historical excavations and ad hominem swipes, glaringly absent was any serious effort to question our analysis or offer a rival set of justifications for why their fiscal numbers did make sense.

The prickly response speaks to the deepest worry I have about Reform: they are treating basic questions about their plans for the country as political volleyballs, not real challenges to be grappled with.

Few responsibilities are more momentous than running the world’s sixth-largest economy, taking decisions each day that will affect tens of millions of lives. The stakes, complexity, and consequence of governing should weigh uncomfortably on anyone seeking high office—doubly so now, when Britain is already in a bad way.

For me, that above all is what makes their shallow glibness so distasteful. Proper patriots would meditate on the enormity of the job ahead, not lash out at those pointing out where they’ve gone astray. The last thing the country needs is more chancers.

For a look at the politics of Reform’s upswing, I cannot recommend my colleague Matthew Holehouse’s recent podcast on Nigel Farage highly enough—it perfectly captures the peculiarity, and flux, of this political moment. Matthew followed the Farage show around the country in the months leading up to the local elections, just as a Reform UK government began to stop feeling like an impossibility.

Net zero is a topic I do want to write more about soon, and am in the process of stress-testing my views. Do feel free to shoot my way any interesting reading or people to speak with.

I used a mixture of ‘ready reckoners’ from HMRC and the IFS, plus my own back-of-the-envelope calculations and some of Dan Neidle’s—and also cross-referenced the largest numbers with outside experts. Given the scale of some of the changes Reform is proposing, all of this is necessarily rough. But on quite a few occasions, most notably on Reform’s plan to tier reserves at the Bank of England (which they claim would raise £35bn/year), I went just to the limit of what was realistic in granting them the benefit of the doubt.

Gratifyingly, our analysis helped catalyse a news cycle on Reform’s bad ideas. Dominic Lawson, for instance, leant on it in the Sunday Times.

An aside, but I wish more political figures had the courage to argue that a broad tax base is civically healthy—lifting people out of income tax (or any other tax) sounds appealing, but undermines the sense that governing is a shared project, to which all Brits contribute. To be clear, this is a cross-party affliction: Labour’s national insurance changes in the October Budget played the same trick, the Tories ran on eliminating self-employed national insurance contributions in 2024.

Here, the giveaway has actually gotten more generous since the last election—back then, only estates below £2m would get away tax-free.

Reform has held off on offering details on how it’d define “essential” migration but plans on a cap of some variety, one assumes not a very high one. My colleagues have a good primer on the “new nativism” of modern anti-immigration politics, walking through the main arguments and where they do or don’t hold water.

Now could well mark a high-point in Reform support, and we could all look back in a few years and find articles like this breathless and premature. But the latest polls are the best guess we have.

The closest to a substantive criticism we get here is asking why The Economist didn’t similarly scrutinise the fiscal cost of Rishi Sunak’s furlough. A few issues with that:

First, most obviously, The Economist did run a cover entitled “After the disease, the debt” in April 2020 on precisely that question, applied to governments across the world.

Second, I’d gently suggest that a one-off cash injection during a global pandemic is not quite the same as a recurring set of unfunded tax cuts done outside a crisis (but potentially creating one).

Third, one’s attitude towards big new government borrowing probably should differ when interest rates are near-zero, versus 4-5%.

I have just stumbled across this super piece, and have promptly subscribed. To take up your request on net zero, people I find well worth reading/talking to include Dr Simon Evans who produces detailed, sourced analysis on it for Carbon Brief (and was environmental journalist of the year in the British Journalism Awards a couple of years ago) and James Murray, Editor of Business Green, who - for my money - is the best envronment/energy commentator writing at present (much, though not all, of his stuff is behind a paywall, alas). I'll shortly send links to a few documents to the email you give below. Best, Geoff

I'm Reform-curious, in that I want less immigration, less crime, less "net zero"*, and more freedom. And I've lost faith in the Conservative Party. But . . .

Farage is an admirer of Donald Trump, which I find a bit worrying

Their cloud-cuckoo-lander economic ideas

Their deputy leader, Richard Tice, is a dimwit

What I really want is a political party led by Matthew Syed, the Sunday Times columnist. I want all the same things he wants.

*By "net zero", I mean environmental policies that will cost a lot of money, or inconvenience a lot of people, but won't actually make any noticeable difference as far as global warming goes. For example, subsidising the wood-burning Drax power station. Policies that are performative, rather than effective.

I expect you've already seen this:

https://www.samdumitriu.com/p/reforms-very-expensive-pylon-plan

Relevant to net zero:

https://unchartedterritories.tomaspueyo.com/p/we-can-already-stop-climate-change