Here’s a story that I’ve bored plenty of friends with, but never written up publicly. For an awful and surreal week last autumn, my parents’ dog was stolen1. Oreo is the sort of creature for whom “lively” is at best a polite euphemism—an energetic, opinionated and food-motivated Smooth Fox Terrier. He came into the family as a puppy while I was at university. Now he’s getting a bit grey, but age seems only really to have made him mildly arthritic, not any more solemn or dignified.

Retrieving him was a six-day saga, but I want to focus here on a specific episode that was equal parts maddening and illuminating. I’ve spent quite a bit of time over the past few months looking at Britain’s frail public services for The Economist, and will discuss some policy-level observations later on. But there’s little substitute for feeling the dysfunction close-up.

Thanks to an online informant (and the fact that the thief put Oreo on TikTok), we had identified the thief and placed her, with Oreo, at a specific restaurant in Hastings. The thief had gone to Hastings after getting spooked by the “DOG THIEF” posters we’d plastered around London, using CCTV images of her that we’d managed to wangle out of a dog-loving restaurant manager nearby. I’d slipped away from Monday work meetings to help with the search, and was in the passenger seat manning the phones while my father drove from London to Hastings.

The local police in London had been sympathetic but not vastly helpful since Oreo was stolen on the previous Tuesday. Now, though, I was more optimistic. We had confirmation from a waitress at the restaurant, which we’d just rung up, that someone matching the thief’s description, with a small black-and-white dog, was eating there as we spoke.

Next, we figured, it was time to get a hold of the Sussex police, who cover Hastings. Easier said than done. To start, I called 999 and was put through to a helpful operator covering South London, where the car was at the time. After a few minutes’ explaining the context and verifying that I wasn’t a loon, she told me to sit on the line while she dialed up Sussex. Cue a minute of waiting and a repeated faint buzz on her side of the line. Then another minute, then another. Finally, the buzzing stopped. Sheepishly, she told me they hadn’t picked up. My best bet, she said, was to dial 101, the non-emergency number, while she kept trying.

When you’re stressed, panicked, and up against the clock—we didn’t know how long the thief would stay put—working through an automated phone tree with poor voice recognition is a rare form of torture. (“Which police force are you trying to reach?” / “Sussex Police” / “Did you mean … Suffolk Police” / “No, Sussex Police” / “I’m sorry… I didn’t quite get that. Could you try again?”, and so on). Twenty minutes later, after several tries and round upon round of interminable menu options, I reached an actual person at Sussex Police.

She listened politely for a few minutes, wearily apologised, and said she couldn’t help. “We don’t have the resources to look into this.”2 She suggested that I ask the Met to send someone down to Hastings. I pointed out that this would be a two-hour trip each way and, besides, we didn’t have long before the thief left the restaurant. She remained unmoved. I tried stressing that this was a central spot, not far from Hastings’ main thoroughfare. Couldn’t a few officers in the area at least stick their head in for a minute or two? “We have no-one on patrol nearby. Anyway, what would we do then? We’d have to process the dog, and we don’t even know if it’s really yours.”

Rotely, I thanked her for her time, winced and cursed, and hung up. Eventually, the London 999 operator managed to get through to Sussex too. So, ten minutes later, someone else from the Sussex Police called. She said that they wouldn’t be able to do anything until the Met sent over a report. I offered the crime reference number but that was no good: their IT systems weren’t joined up. The Met would need to send the information through themselves and, no, Sussex couldn’t reach them to ask—I’d have to speak to the Met myself. So I did. Thankfully, the Met officer assigned to the case was around. I asked him if he could send the information over. He warned that it would take some time. His only way to reach Sussex would be through the 101 non-emergency line and that awful phone tree. I gave up. By the time the file even reached Sussex, the thief would have been gone anyway.

Later that day, we did manage to get Oreo back, in a hand-over at a petrol station on the outskirts of Hastings. Predictably, the Sussex police were not involved. A few exceptionally kind members of the public made the difference, but that’s a story I’ll save for another article3. Time, shortly, to get to the point.

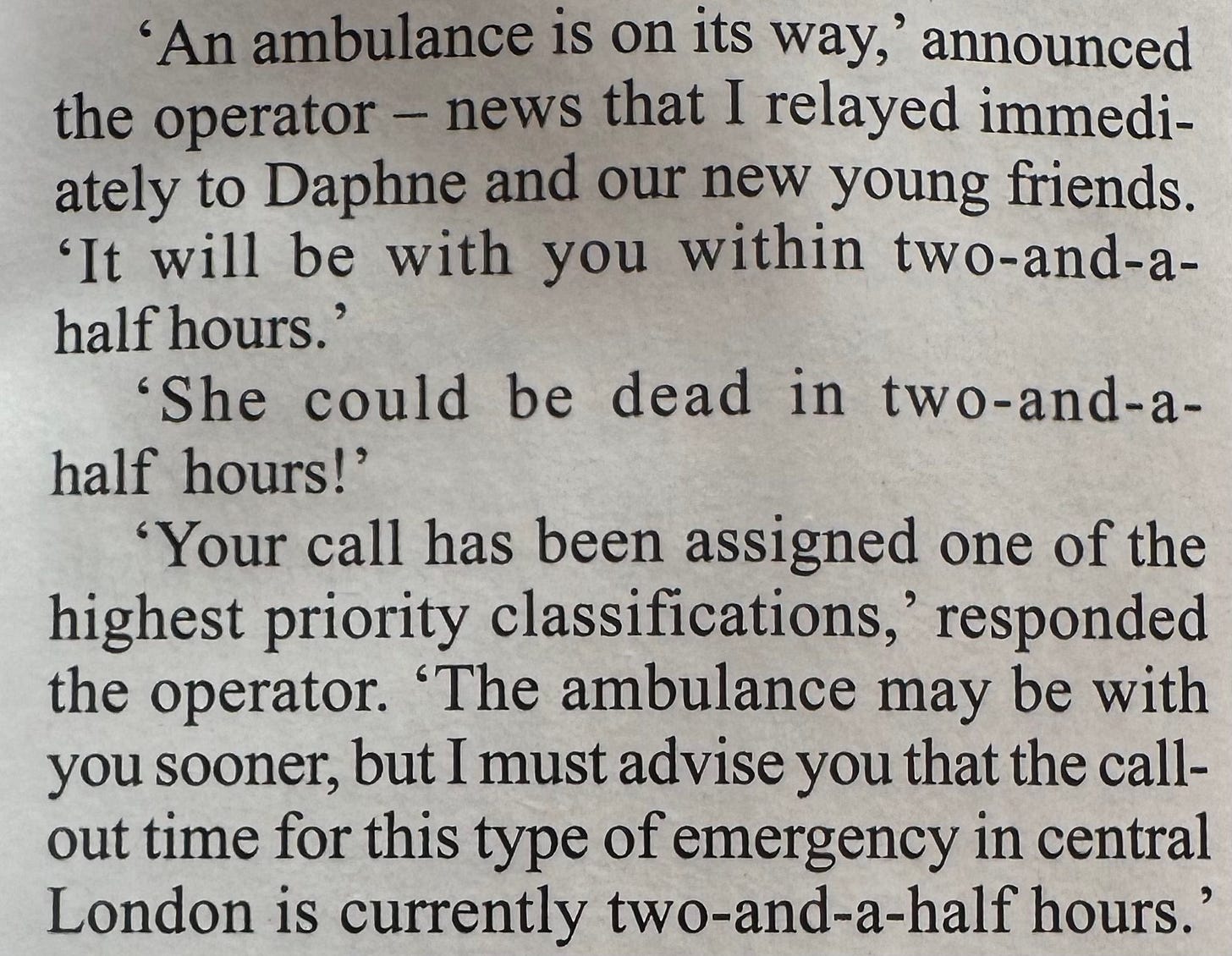

One more anecdote, though. A few months after we retrieved Oreo, I stumbled on an article in The Spectator that encapsulated exactly the same feelings of bewilderment and frustration I felt that day—the dispiriting moment when you realise that your latent expectations for how much the British state will help you are wildly out-of-kilter with the bleak reality. This time, the topic was not policing but the ambulance service.

An old lady, Daphne, had fallen on the street, knocked her head, and was bleeding. I’d encourage you to read the whole thing, but I photographed an especially shocking passage in the print copy I was reading at the time. Owen Matthews, the writer, goes through exactly my experience with the Sussex police: a gradual realisation that his standards were set much too high.

Still, it’s always tempting to dismiss an episode like this as an unfortunate one-off that just happened to be highlighted because a journalist was around. So I was especially shocked to open WhatsApp a couple months back and see this text from my father.

An 85-year-old man had taken a tumble on the street just outside my parents’ front door. Along with another passer-by, my dad called for an ambulance and—even though this was in central London, and the nearest hospital was less than ten minutes’ drive away—got nowhere. He eventually drove the 85-year-old to the A&E himself.

I sent the Spectator piece over to him. They matched almost beat-for-beat.

A few weeks later, I dug around the ambulance callout time data for England, which you can see in the chart below, split out by category: C1 is a life-threatening emergency (e.g. serious heart attack), C2 is an emergency (e.g. stroke), C3 is urgent (e.g. most sorts of broken bone) and C4 is less urgent (e.g. minor burns).

Two patterns stood out to me. Both would keep recurring as I started looking into woes facing British public services. First: the “Covid hump”—everything got worse during the pandemic, and then never fully recovered. Second: the triage—thankfully, the data suggest that life-threatening emergencies still mostly get seen to quickly. But everything else, seemingly including pensioners bleeding into the flagstones, now gets deprioritised.

The chart also reminded me of two others that I’d made for earlier articles. One was about Britain’s driving-test backlog, which shows a quintessential Covid hump. When I wrote that piece last September, my back-of-the-envelope estimate was that the backlog would take something like five years to clear at the present rate. In the meantime, hundreds of thousands of young people would be denied the freedom, independence and financial opportunity of being able to drive. Last I checked a few weeks ago, the latest data are pretty much in line with that trend—just four and a half years to go, then!4

The other was a chart I made—or, more accurately, procured from the Resolution Foundation—on Britain’s rising working-age benefits bill. Here, you can see the triage effect in action. Spending is up across the board, but the key driver again is the most acute, expensive stuff: health-related benefits, reflecting (roughly equally) more mental health claims among under-50s and more physical health claims among over-50s.5

Why nothing works: a few ideas

Each of these anecdotes or data-points seems to be circling around the same point: that the British state seems to have gotten markedly less functional, and that this deterioration has happened surprisingly quickly.

That leads, again and again, to a saddening dynamic. People’s hopeful expectations, formed by recollections of how the state used to work, or maybe just folk-memory from TV detective shows, slowly grates up against what actually exists.

Wounded pensioners or stolen Smooth Fox Terriers are the sharper end of that, but the same thing happens in a smaller way every day too, as people drive down pothole-ridden streets or have to ring the door to enter their local Tesco and buy a pack of chicken breasts with a security-tag. Shoplifting, incidentally, is another chart that looks like those ambulance callout-times. There is one difference, though: since the pandemic, shoplifting has just kept getting worse.

In this weekend’s edition of The Economist, I took this topic on. I opened my leader article on Britain’s fraying social contract with one more anecdote.

“Lodged incongruously on the metal cladding of an office block in the City of London, a blue plaque marks the birthplace of Thomas More. In 1516 he published “Utopia”, sketching out a vision of free hospitals, compulsory schooling and full employment—a forerunner of sorts to the welfare state. Nearby, blue plaques of a different kind are spray-painted on the flagstones of London’s pavement. A cack-handed publicity stunt by the local police, each commemorates a spot where a Londoner’s phone was recently stolen.

The competing plaques capture the gap between aspiration and reality in Britain. Eventually, More’s intellectual descendants brought some of his better ideas to fruition, building modern welfare states across the rich world. But underpinning the ever-higher taxes this arrangement demanded was a deal: the state would provide a safe, orderly public realm and run broad, universal services to a high standard. Increasingly, the British state is reneging on its half of the bargain.”

The good news is that the City of London Police’s awful spray-painted blue plaques are now fading (I took the second photo on Friday). The bad news is that Thomas More’s commemoration continues to be attached to a bleak office-building alcove, a few feet up from a fire exit sign. Surely the man has already been through enough.

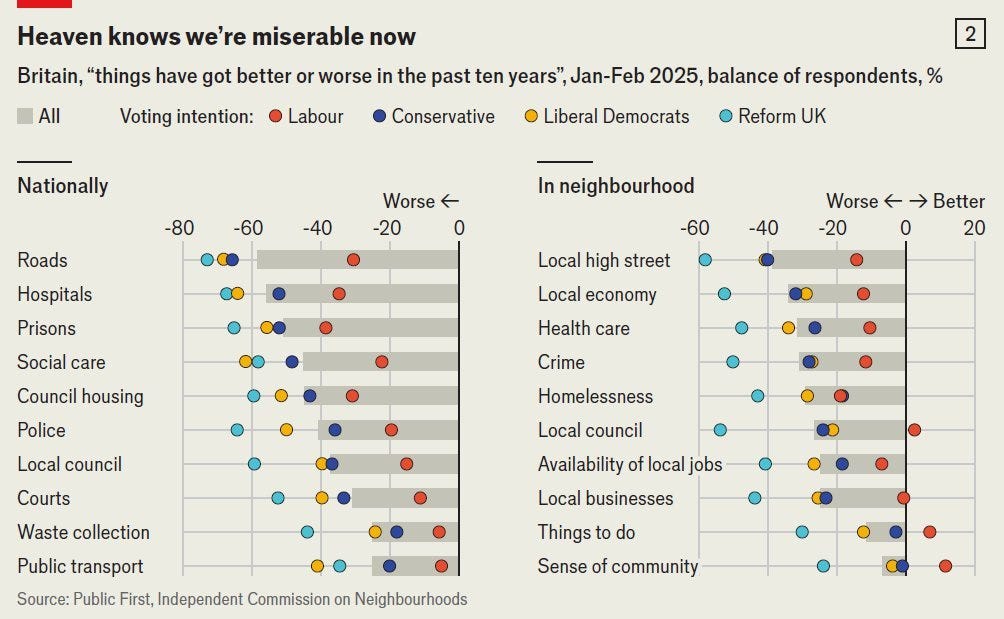

Nor am I unusual in feeling this way. Public First kindly ran some polling for me, and shared some other polling they’d already done for the Independent Commission on Neighbourhoods, showing shockingly widespread agreement that something is awry in Britain today.

So what’s caused this mess? After all, the pandemic is now almost five years ago and taxes are set to hit postwar highs. Surely there should be plenty of money to go around?

Answers differ across arms of the state. I’m also certainly not totally satisfied with any of these explanations—and would be interested in what readers think I’m missing6. But there are some themes that did seem to come up repeatedly. I mainly focused on the first two in my Economist articles this week.

Acute need has worsened, and the state is awful at cost-control

If I think of the places7 where state spending has grown most over the past decade or so, a common theme seems to be that spending on a narrow group of some of the worst-off seems to have exploded. One example is working-age health-related benefits, which I mentioned earlier. Almost a million extra people are now out of work due to poor health compared to 2019, a major slug of that seems to be young people with mental health issues.

Another is local government spending, which these days is mostly social care for vulnerable children and adults, as the chart below lays out.

Much of the rest is special-needs schooling, now a colossal cost centre, or temporary accommodation for the homeless. Few can fault spending money on helping the neediest (hence money still being spent), but the way that’s been approached is pretty shocking. The the scale of the increase in spending on special-needs schooling and transport over the past few years is pretty remarkable.

Or take the asylum system, where progress at getting people out of extraordinarily expensive hotel accommodation seems to be moving at a glacial pace.

Those are just the areas I’m more familiar with—I expect there are plenty more that are similar.

The double-whammy of Covid and austerity has shredded state capacity

There would be something pleasantly reassuring if the problem with public services was just that the state had been cut back too far in the austerity years, and now was working on an unviably slim budget. All it’d take then would be a few well-judged tax rises (VAT broadening, anyone?) and the problem would go away. On parts of the further-out left, my sense is that a version of that view (swapping VAT for wealth taxes) basically holds.

The more troubling reality, though, is that even in the parts of the state that are a little smaller than pre-austerity, the difference isn’t huge. Here’s spending8 on public order, for instance, which covers police, courts and prisons9—among the most dysfunctional parts of the state at the moment.

Clearly, the cuts in the 2010s were part of the problem. But mostly-undoing them doesn’t seem to have helped much. A lot of the problem seems to be staffing churn, and hiring less-experienced officers10.

Something similar, though with Covid as the breaking-point shock, seems to have happened with the NHS. There, spending isn’t even down compared to pre-Covid, but again a public sector bureaucracy that’s had a difficult few years is struggling to mend itself.

Bottlenecks are bottlenecking each other

Chaos in one part of the system often compounds itself elsewhere. Courts are blocked and slow-moving, but does that matter if the prisons are full? Hospital beds are full of patients who don’t have any medical reason to be there, but social care is such a problem that there’s nowhere else to put them. Patients are stuck in ambulances because A&Es can’t take them, which then means there are too few ambulances. Police—at least until recently, there have been some efforts to address this—were spending a pretty troubling amount of time dealing with non-crime-related mental health episodes, because no-one else would. Blockages in A&E wards left police officers stuck in queues too, unable to hand patients off to medical staff and get back to stopping crime.

Britain’s public sector seems to be extraordinarily brittle, and the past decade has clearly had a few shocks too many.

Low esteem and lower pay have led to talent attrition in government

Compounding all of this is the false-economy of having poorly-paid staff steward vast budgets. The appeal of public service, plus career stability and good pensions, ought to be enough to keep a steady trickle of bright, high-energy people in government.

But I’ve come across enough disillusioned ex-civil-servants recently that I really do worry the pay differentials have got too acute. One ex-Treasury type I met recently, now in finance, just said: “I decided I wanted to be able to afford a house in London one day.”

And the flip-side of low quality frontline services is that working there becomes unappealing too—no-one becomes a police officer only to repeatedly disappoint crime victims by failing to help them.

Government has strangled civil society in red tape

If the state steps back, one natural response is for civil society to step up. (Another, less inspiring, vision is that a parallel privatised state emerges for those willing to pay—which is already the case in parts of health, policing and more.)

But one anecdote from a councillor that I spoke to for my most recent piece, Alan Connett, a Devon Lib Dem, stuck with me.

“There’s a residential road, with two small areas of grass: two triangular areas about 8 foot by 4 foot. The council doesn’t cut them because they’re not cutting the grass anymore. The resident opposite says: ‘I’ll cut the grass’. Years ago, he wouldn’t have needed to have asked. Everyone would have been happy, it would have improved the street scene. The council says ‘You need to go on a training course, have you got public liability insurance?’. The chap says ‘I don’t know if I’ll bother’. The grass doesn’t get cut. …

People feel that they are not regarded as able to contribute, actually we should be embracing them.”

The new Martyn’s Law, which imposes hefty security requirements on venues, and already seems to be prompting at least some events to shut down entirely, raises similar issues.

Tolerance for social disorder has risen

One rather troubling dynamic in America has been a growing desire—most prevalent in parts of the big-city left—to treat concern about disorder and crime in public spaces as hand-wringing and moralising. (The past year or two seems to have been a real tipping point against that attitude.)

Britain never had it quite so bad, but there’s a certain “grin and bear it” attitude inscribed pretty deep in the national psyche, which tends to mean people don’t complain. The Liberal Democrats’ unexpected proposal of fines for people playing loud music on public transport struck me as encouraging. Perhaps the dam is breaking here too.

Politicians were simply too distracted

Another argument that used to come up a lot in the Brexit years was that, abstractly, it seemed worrying that Westminster was monomaniacally focused on Brexit trench-warfare, and not on tackling the country’s many other problems. Covid paused usual government business for more understandable reasons, but had the same effect.

With the benefit of hindsight, we can now see the consequences of some of the slow-boiling domestic issues that were left largely undiscussed (and so also unaddressed) between 2016 and 2022: the housing crisis; a population getting older and sicker; energy scarcity; decaying public infrastructure, and so on.

Many of the challenges Britain faces today might be looking a lot better if the country had paid attention to them from 2016 on11.

There’s certainly a lot more going on that just those seven, and I’ve deliberately steered clear of the most obvious high-level fixes—like improving productivity growth or rolling out AI in the public sector.

The first dynamic I mentioned, rising need and poor cost-control, is something that feels particularly pervasive, and yet near-absent from public commentary on the state of government finances. Given how hard it is to measure, and that the direct implication of nearly any effort to change it would be to take money away from some of society’s neediest, that widespread silence is hardly a surprise. But the problem remains.

The politics of making places nice

There’s a story to be told about how a crumbling public realm and dysfunctional public services breed dissatisfaction and populism. I’m enough of a cold materialist that I have quite a lot of sympathy with that view. I wrote up a soft version of that argument in a recent piece:

“The politics get harder-edged for those unable to pay [for privatised state alternatives]. Reform UK voters are especially angry about the public realm. Meanwhile, promises to fill potholes have become a tired political cliché. The last government’s “levelling up” plans represented a similar impulse on a grand scale, and met a similarly disappointing end. High-minded aspirations struggle to survive contact with cash-strapped realities.

That’s a pity, says Rachel Wolf, a political consultant who co-wrote the Tory manifesto in 2019: politicians need places where they can deliver quick, visible and cheap change. “There aren’t many areas where they can do that; one of the few is the public realm.” Setting the streetscape right could, she says, be “a version of [the] ‘broken windows’ theory for politics”. Mr Giuliani’s unlikely fan club is growing.”

But—as I hope to write more on soon, I’m also wary of ‘false consciousness’-style attitudes that project motivations onto people who are perfectly capable of explaining their voting choices themselves. If Reform UK voters say that they’re unhappy about immigration, there’s value in just believing them: not everything is sublimated economic anxiety.

The good news is that (contra a recent piece in the Times), Britain is still a functional, high-trust society. But the warning-signs are flashing. Politicians that ignore them will struggle.

He’s safely home now and has recovered well. The thief pleaded guilty last week and is serving a few weeks in prison—less, my sense is, because of the severity of this particular offence, but because it came on top of a colossal number of prior ones.

All this is paraphrased since, unsurprisingly perhaps, I wasn’t taking notes at the time. The thrust, though, I promise is entirely accurate.

I’ve been putting off writing something proper about all this until I had time to get a bit of mental distance, and once the formal legal processes had run their course. Hopefully I’ll do that over the next few months, though. If any commissioning editors happen to be reading this Substack and are interested, do get in touch.

I should add that DVSA has since announced plans to hire 450 new driving examiners to help clear the backlog. Hopefully that will help, but it’s not shown up in the data yet—and the government’s now had almost a year to sort this out.

This chart doesn’t reflect the government’s cuts to working-age benefits, which were announced the week after I did the piece. But that only changes the forecast, not the outturn data. Also, given the estimated savings are ~£5bn by the end of the decade, but the projected spending increase by then was ~£25bn extra, the differences even there wouldn’t be all that huge.

In a lovely expression of the proclivities of the two platforms, the most common hostile response I got on Twitter was that I was underplaying the impact of immigration, especially the post-2021 wave; on BlueSky it was that I was overplaying the issue altogether and, besides, retailer survey data on shoplifting might as well be made up. Neither strikes me as quite right.

On immigration, I worry particularly about monomania—thinking that +800k/year in net migration was unworkably high is an entirely reasonable position, as is worrying about the fiscal impact of the asylum system—but the “immigration theory of everything” mentality that seems to be getting increasingly popular on the right (and in parts of Blue Labour) feels like it substitutes a convenient bogeyman for the harder work of analysing why governance in Britain has become such a mess.

Putting aside debt interest, the single largest category.

Incidentally, the IFS tool this screenshot is taken from is really worth playing around with.

If you can tolerate a pretty unremittingly grim read, this piece by my colleague Tom Sasse on prisons post-Covid is excellent.

Onward has a great report on staffing issues in the police, and staffing is also something that comes up a lot just speaking to people in that world.

The Conservatives deserve most of the blame here, but you can fault Labour too—most of those years were spent in Corbynite solipsism, pushing an agenda that was as detached from Britain’s genuine public policy problems as hard Brexit was.

I've had many experiences which showed me how little I can rely on the state, but two which stick out were my bike being stolen then two or 3 weeks later the police rang and asked if I had heard anything and more recently I was driving with my wife and spotted a man lying in the road down a side street, I turned the car around and went back to find a young man, probably 30, so drunk he couldn't sit up or speak, sleeping with his eyes fully open and his pupils two different sizes (which can indicate head trauma). Called 999 and requested an ambulance only to be asked "does he want to go to the hospital" and I explained that as I had already stated he was not conscious and was not responding to any stimulus.

They told me they didn't want to send an ambulance if he would refuse to go to the hospital and I ended up arguing with the dispatcher and demanding her name because if I left and this man aspirated his own vomit I would not be held liable for his death. He couldn't refuse to go to hospital because he was unable to speak. Thankfully someone local who knew him arrived and relieved me and told me they would wait with him for the ambulance.

Like if a man being totally unresponsive with a head injury isn't enough to get a blue light ambulance what is?

Utterly utterly depressing. Hardly the point but I found strange comfort from this bit:

"When you’re stressed, panicked, and up against the clock—we didn’t know how long the thief would stay put—working through an automated phone tree with poor voice recognition is a rare form of torture. (“Which police force are you trying to reach?” / “Sussex Police” / “Did you mean … Suffolk Police” / “No, Sussex Police” / “I’m sorry… I didn’t quite get that. Could you try again?”, and so on). Twenty minutes later, after several tries and round upon round of interminable menu options, I reached an actual person at Sussex Police."

I've always best myself up on this for not making the effort to develop a 'British accent' after a couple of decades living here (in my own home I stand out alone on this) and put any struggles with automated systems down to that. Turns out the systems are equal opportunity rubbish to everyone.