Fifteen thoughts on the Budget

A quick verdict on Reeves Round II, plus an utterly wild OBR leak

I’ve now also published a next-day follow-up to this piece, which you can read here:

The best place, naturally, for a top-to-bottom read on how to interpret Rachel Reeves’s latest offering is the pages of The Economist—you can read what my colleagues thought here, here and here.

Still, seeing as this is the first British fiscal event in a while where it’s no longer my job to write something up for those pages, I thought I’d freelance a little. So here are a few rough, day-of, impressions of the Budget, pinged over from across the Atlantic. Speed beats structure1 here, I concluded, so forgive the slightly haphazard layout.

1. What a mess at the OBR

Pretty much every quarter, pretty much every public company manages to announce its market-moving earnings without accidentally uploading them early and botching things. The fact that the Office for Budget Responsibility seemingly cannot, and managed to put out its full assessment and forecast hours before the Budget, is an utter disaster.

Cock-up rather than conspiracy, I assume, but anyone who caught it early could have made a fortune trading on the information. All rather unedifying—if helpful to those of us trying to churn out budget analysis on a deadline.

2. More spending, more taxing, more borrowing

But more important, what was actually in the Budget? After all, two landmark fiscal events, plus a messy fudge last March, should be enough to give a sense of how this government operates.

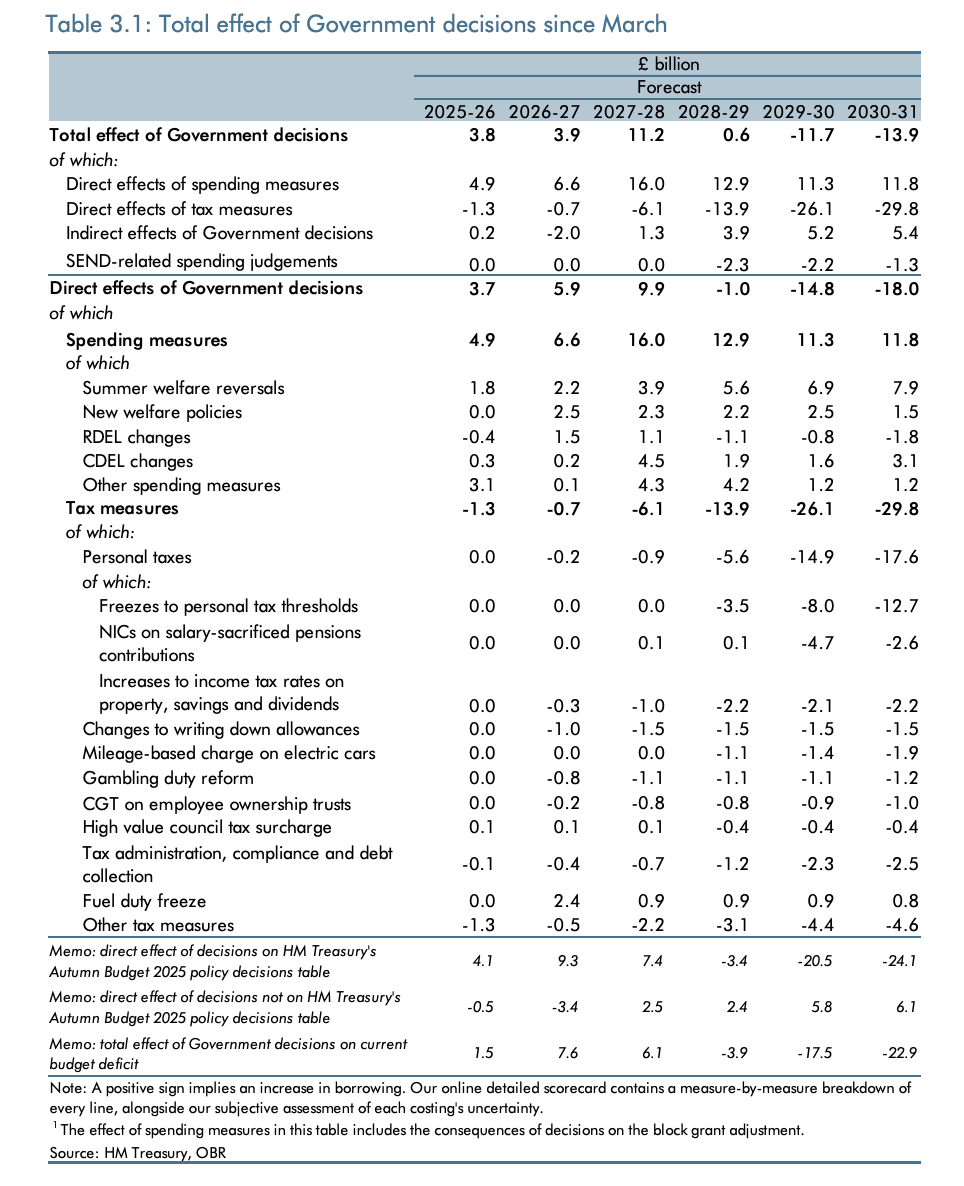

Add up everything the government has done, across all three fiscal events so far, and you get the chart below. The story is pretty clear, and this budget mostly adds to it: higher taxes, more in extra spending than those higher taxes raised, and extra borrowing to make up the difference. The totals involved are pretty vast: about £79bn (2.2% of GDP) in extra tax receipts, £96bn (2.7% of GDP) in extra spending and £17bn (0.5% of GDP) in borrowing by the end of parliament.

Big moves, for a government often criticised for doing too little2. This time around, the mix skewed more tax-heavy, allowing the Chancellor to slightly narrow end-of-parliament borrowing and build up a thicker fiscal buffer.

3. Quite the front-load

To get a better measure of this budget, though, it helps to look at the years that don’t determine the Chancellor’s fiscal margin.

Over most of the next five years, the budget leans lighter on tax and more on spending. Clear echoes, here, of the “fiscal fictions” with which Labour so vigorously criticised the last few Tory budgets. Few can resist the eternal temptation to kick the can down the road and borrow more in the short run.

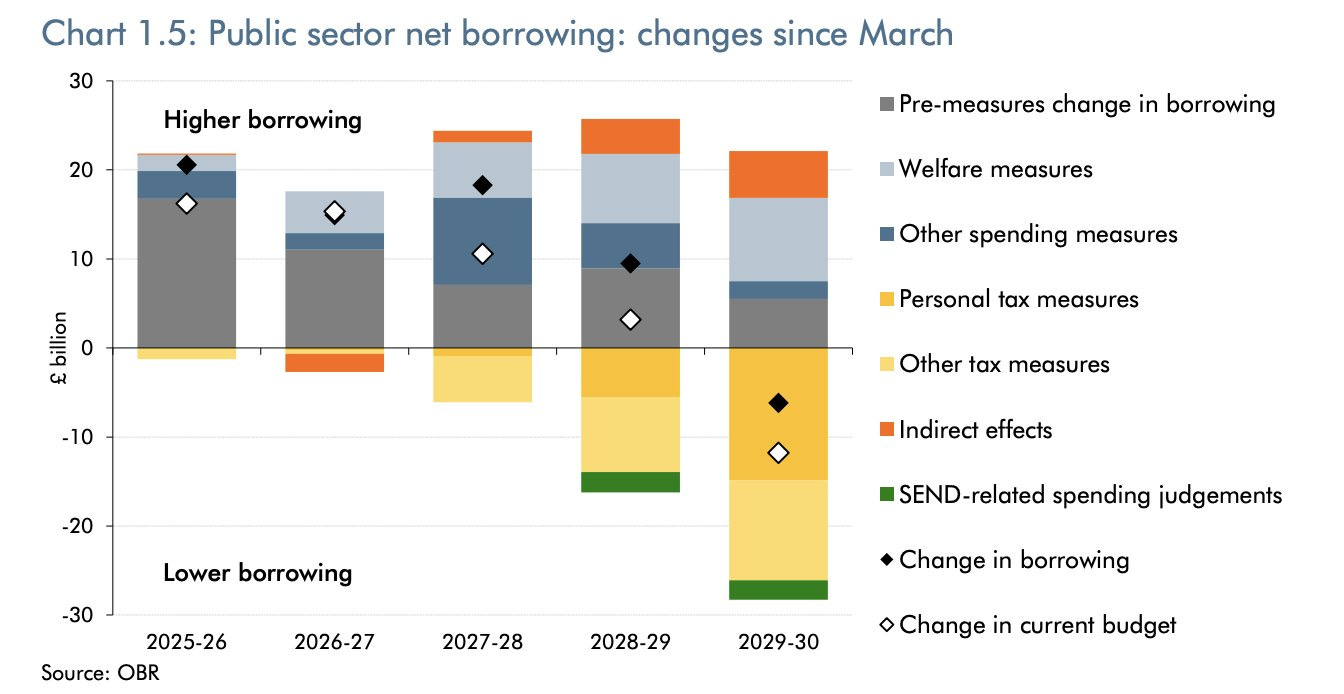

The result is this quite entertaining chart from the OBR. £20bn in extra borrowing for three more years, before tax rises swing in just in time to rescue the Budget’s compliance with the fiscal rules. A rather entertaining definition of “borrowing falling as a share of GDP in every forecast”, as Reeves boasted in her Budget speech.

Governments have, of course, been playing this game forever. Here’s a chart the IFS put together a few years ago showing that, come rain or shine, the first three years of a forecast period get a spending boost. Chancellors then fiddle with the last year to ensure fiscal compliance. No wonder that, if you talk to folks actually involved in gilt trading, they pay far more attention to new issuance over the next few years than any tenuous claims about what the government will do in five years’ time.

To give the chancellor her credit, she is gradually moving towards a three-year fiscal horizon, which ought to help with this dynamic a little. But in the mean-time, she is happily capitalising on the room for fudge that the fiscal rules leave.

4. The bond vigilantes’ verdict

The fact that every fiscal event in Britain is now conducted with half an eye on the same-day reaction of the gilt market is a pretty remarkable cross-party failure. With that said, where did the vigilantes land?

This time around, the verdict appears to be merciful—at least relative to the rather-glum expectations that had already been priced in. Gilt yields are down marginally, and actually down especially relative to the US. So far, a much more reassuring market reaction than the last budget. It helps that the wider headroom margin that Reeves has bought for herself should prevent any more messy corrective fiscal events like the one in March.

It’s become increasingly popular to say that the importance of the bond market reaction to a budget has become a democratic problem—see Andy Burnham a few months ago, and Zack Polanski more recently.

Two quick thoughts on that, one uncontroversial, one rather more provocative. To start: having to pay attention to whether people are willing to lend you money is hardly an unusual condition. Running big deficits is a policy choice, and one plenty of governments have opted against in the past. Then needing to pay attention to whether the people lending the government that money expect it to be paid back is simply the straightforward consequence of that action.

But also—I’d venture that bond vigilantes are essentially a good thing. Both politicians and voters have obvious temptations to spend now. For governments, dealing the ultimate consequences will probably be left to their successors and they can get a popularity boost in the meantime. For voters, the lack of popular memory of any real fiscal crisis in Britain (outside the somewhat disanalogous currency issues in the 60s and 70s) makes it easy to simply keep pushing for more spending.

A mechanism that prices in the consequences of running unsustainable fiscal policy now, rather than when it’s too late to fix, strikes me as a pretty desirable thing to have in a system of government. And that is, in effect, all the bond vigilantes do.

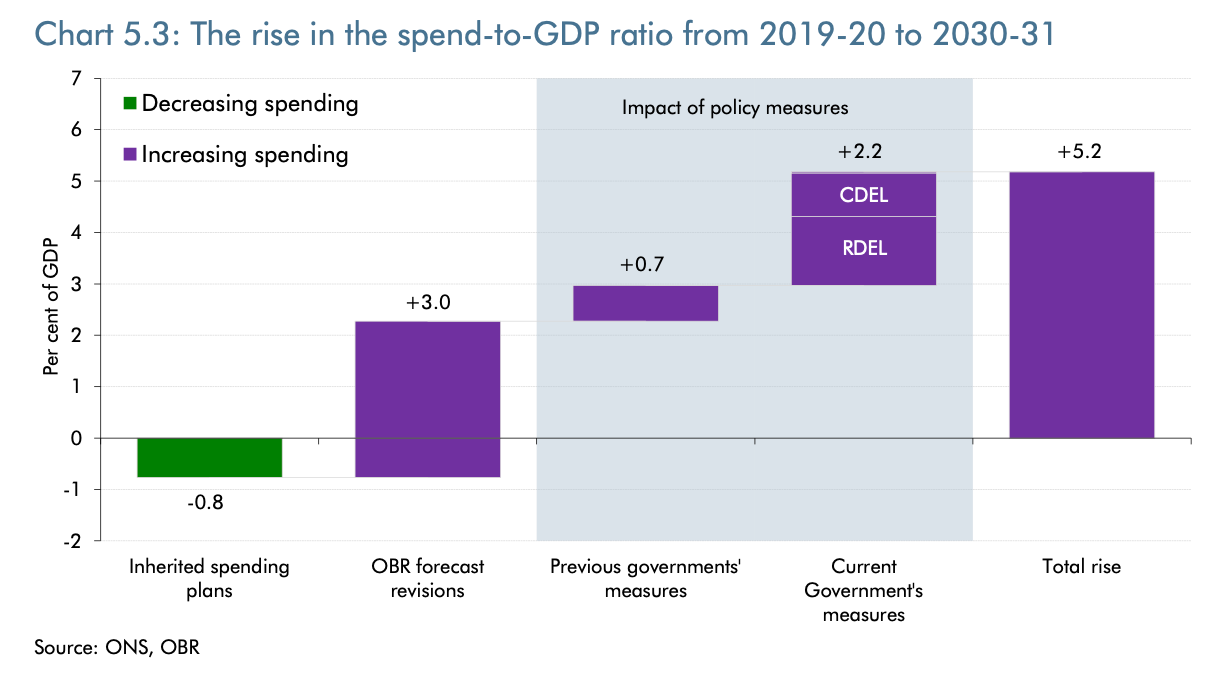

5. A bigger state…

So the sum total of Labour’s fiscal choices has been to expand the state. Over the last ten years, on average state spending was 41.6% of GDP. That has now risen to 44-45%, reflecting more spending and a higher debt interest bill. The chart below shows just how appreciable that shift is.

The OBR also put out its own chart, making a similar point on the rise in spending and disaggregating the causes.

6. … but so far, without much to show for it

People can disagree philosophically plenty about what the right size of the state is. The question for Labour, though, is what that boost to spending is achieving. In my Budget verdict last year, I wrote.

“Across taxes, borrowing and spending, the government is betting big: that tens of billions in extra NHS spending will make a difference, that Britain’s workers and firms can bear ever-higher taxes, that markets will support a big fiscal expansion. Those bets will come good only alongside equally ambitious reforms to the tax system, to public-service provision, to the planning system and more. On that, this heavyweight budget was alarmingly light.”

So far, there still isn’t much to see. The Chancellor had few concrete improvements to public services, aside from a small decline in NHS waiting lists, to point to. Certainly, one can argue that delivering visible change takes time. But pushing almost £100bn a year extra in state spending ought to show up, somewhere. Time to start asking questions if the government isn’t capable of pointing to where, exactly.

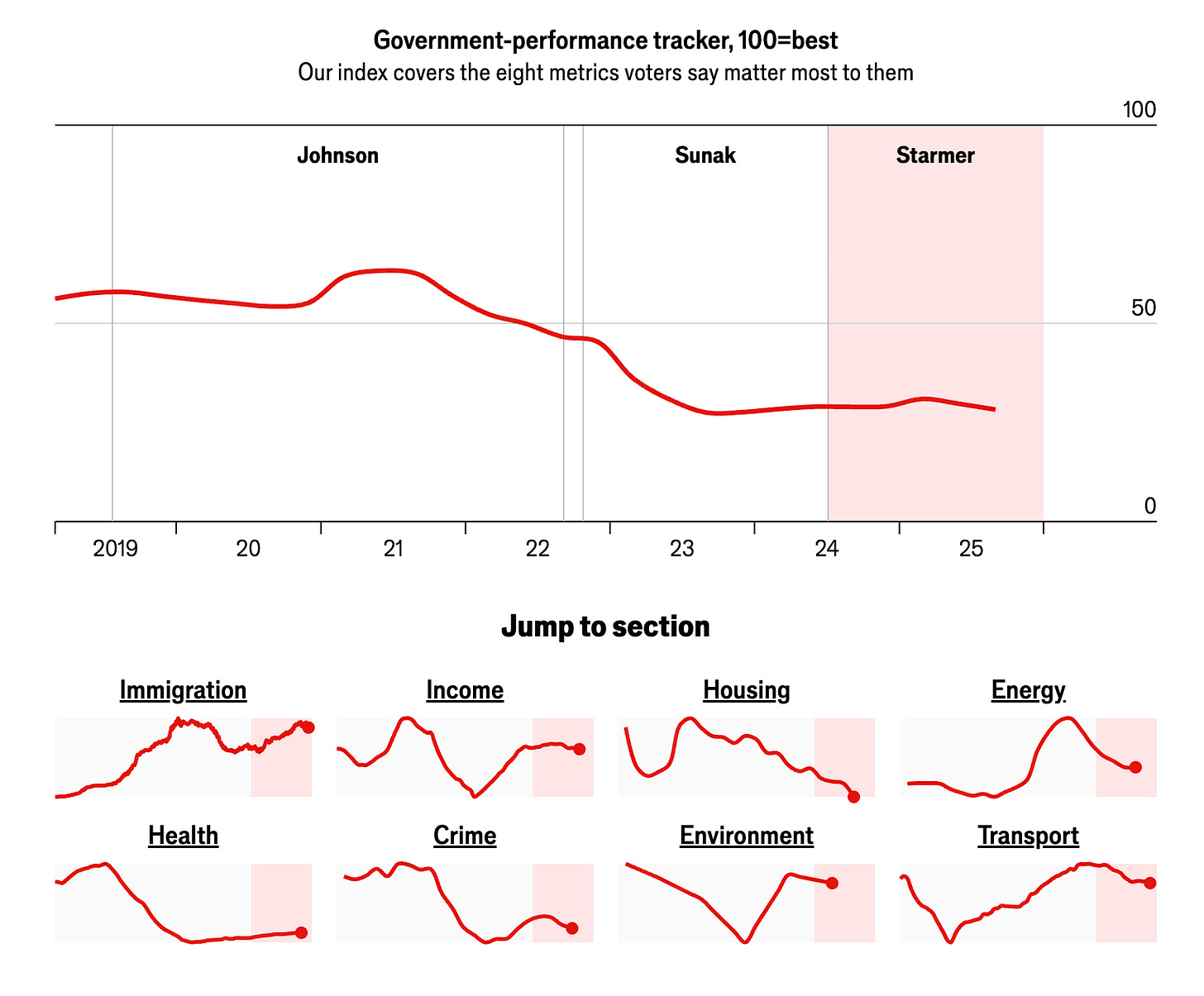

One slightly more systematic tracker of this is run by some of my colleagues at The Economist. We’ve pulled together a range of quantitative measures that voters, when polled, say they care about, like small-boat arrivals, A&E wait times, energy bills and more. Overall, there has been no perceptible improvement so far this parliament.

The government needs a better answer to that disjunct—a sizeable boost in state spending and little improvement in state outcomes.

7. That growth downgrade

The other hefty change this budget was one which was looming for a while, a downgrade in growth expectations by the Office for Budget Responsibility. The Chancellor is right to say that this is mostly a verdict on the past decade, not this government. (I wrote a long look at the issue of over-optimistic OBR forecasts before the last election.)

Even now, though, the OBR has moved from vastly out-of-consensus on growth to only mildly so. It remains among the most optimistic forecasters of growth out there, as the chart below shows. (The OBR points out that the BoE is now, also, on the optimistic end compared to the private sector.)

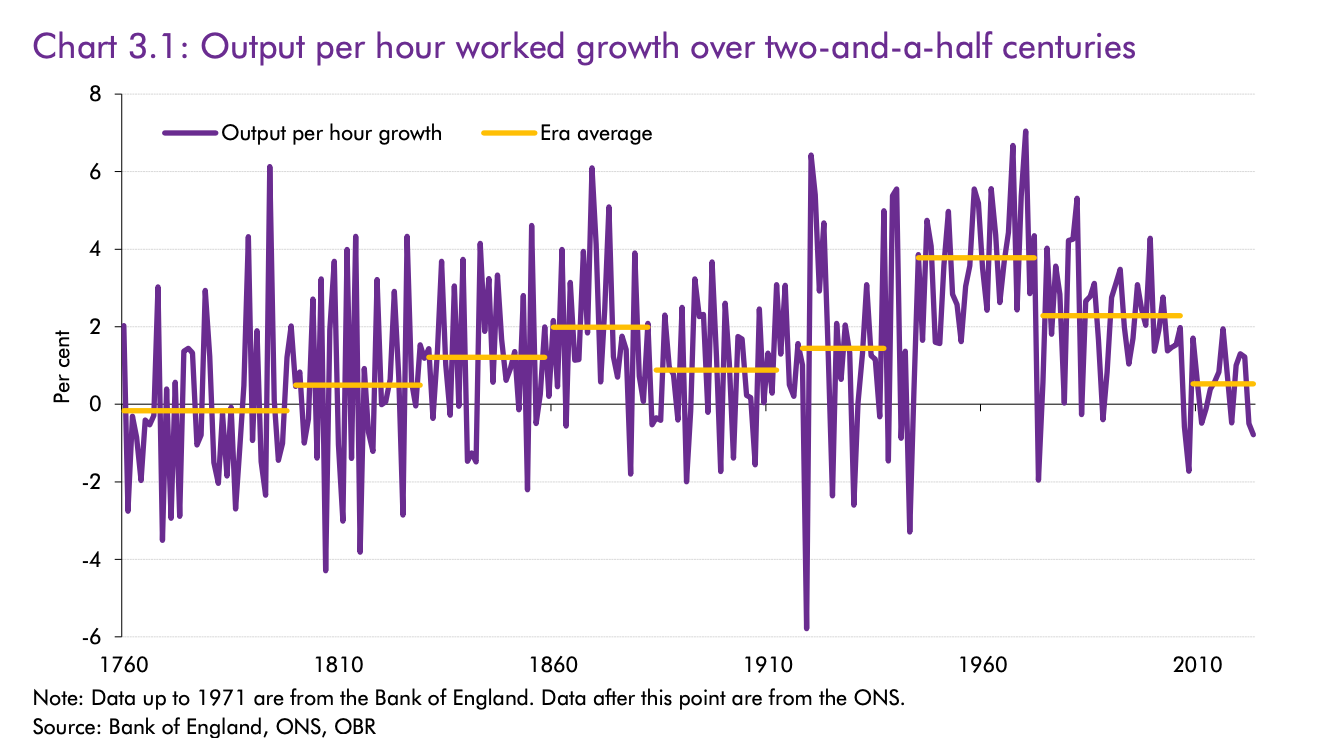

And I did enjoy this longue-duree chart from the OBR in their supplementary productivity note. It makes the point, which is worth repeating when one gets too pessimistic about Britain, that no era lasts forever. Today doesn’t look great, and is about as poor any point since the growth slowdown of the late Victorian era on this chart. But at any given point, the right mix of policy and technology can turn things around.

I should add, too, that I did think Reeves approached the forecast downgrade, philosophically, in exactly the right way: by promising to beat the forecasts. “We beat the forecasts this year and will beat them again.” That, not whinging about the unkindness of the OBR, is the right way to deal with this sort of challenge.

And, as I’ve also written about before, it still strikes me as silly that the OBR produces an entirely de novo macroeconomic forecast, rather than being forced to anchor to market consensus for concepts like GDP growth, inflation, and so on where there exist entire industries dedicated to forecasting those measures well. That would have sidestepped this problem altogether.

8. Back to fiscal drag

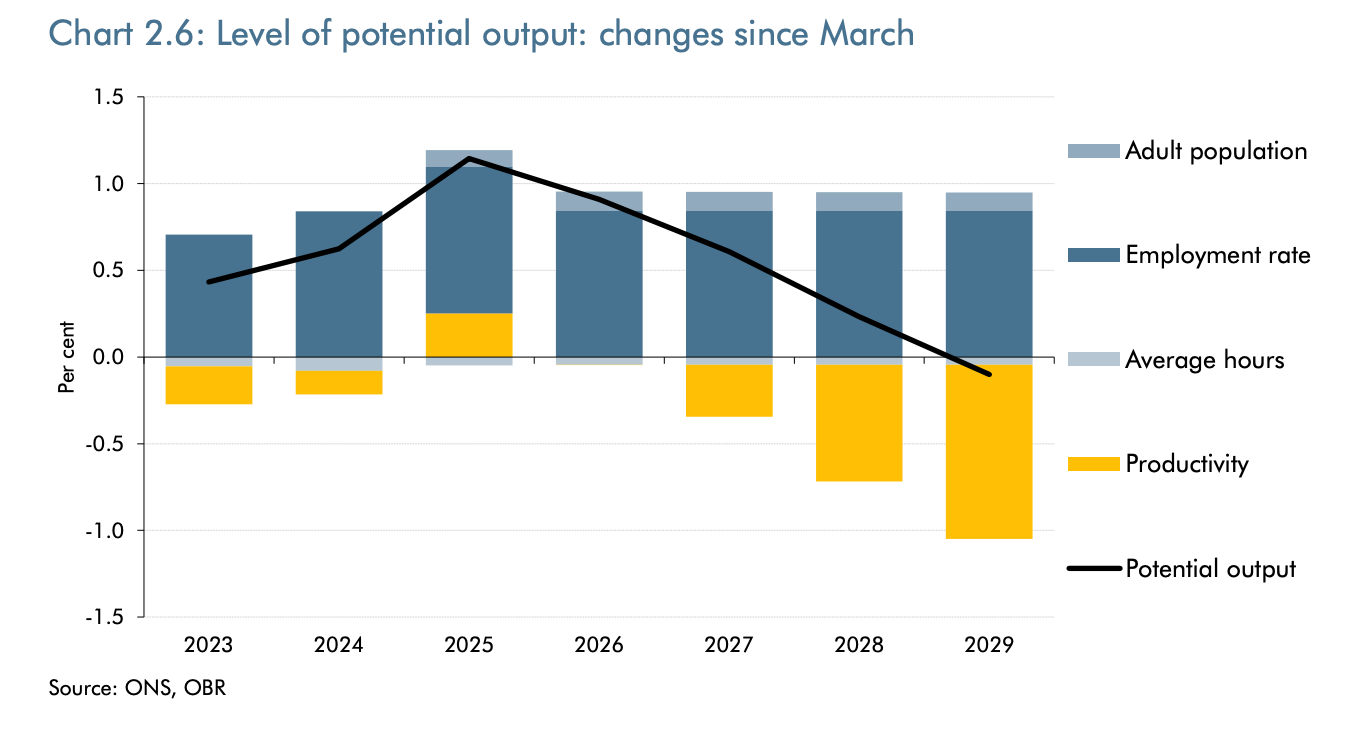

It certainly helped, though, that the overall impact of the OBR’s macroeconomic forecast changes wasn’t as damaging for the government as widely expected. Part of that came from changes to expected employment levels.

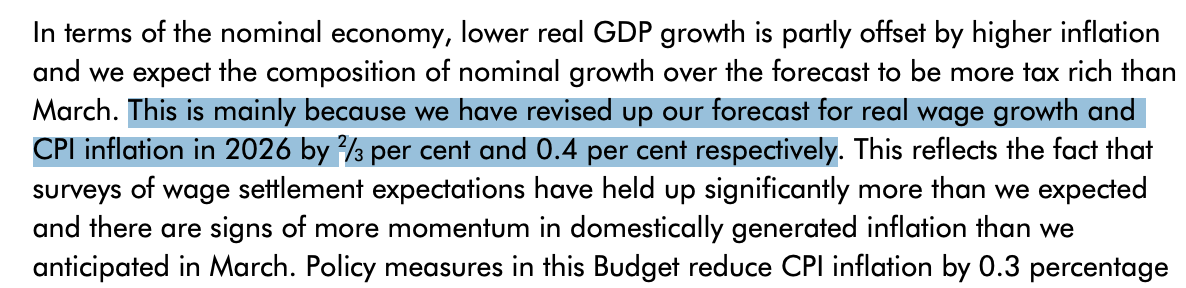

But also, like Jeremy Hunt in 2023, Reeves paradoxically benefitted from higher expected inflation and wage growth, pushing more income into higher (frozen) tax brackets—a dynamic called “fiscal drag.” The OBR uses the diplomatic language of more “tax rich” nominal growth when discussing it.

9. What was in it?

But what did the Budget actually do, at a policy level? The table below is the key summary, for the real geeks. I’d pull a few key bits out.

On the spending side, by a distance the largest single change was the reversals on previously-announced welfare cuts, plus the removal of the two-child benefit cap.

On the tax side, there’s more going on. I’d highlight:

Personal tax rises, mostly back-loaded freezes to thresholds (meaning inflation pushes more people into higher tax brackets) but also applying national insurance to salary sacrifice pension contributions and charging higher income taxes on property, savings and dividend income.

A range of other smaller bits, most notably new electric car taxes (good, better to get them in before there’s a bigger group of EV-owners to lobby against them), higher taxes on online gambling (good, I think), more money from better tax compliance (a classic fudge, I’ll defer to the tax lawyers on how credible that looks) and a few smaller soak-the-rich measures (which I’m less sure about).

10. The fingerprints of the Resolution Foundation

Torsten Bell, who formerly ran the Resolution Foundation think tank, was reportedly closely involved with this budget. RF often does great work, but—reflecting the 2010s era when it really came to the fore—leans very heavily into worries about inequality.

You can see quite a few measures in this Budget where that worldview is at play. Rather than reform property taxes entirely, for instance, we got a fudge to add a special extra surcharge to expensive houses (and do so with an inelegant wedge that is sure to cause distortions). Tax on property and savings income was singled out to be raised; narrowing the gap between the taxes on labour income and assets is a longstanding RF focus. The £2000 cap on salary sacrifice pensions had a similar focus.

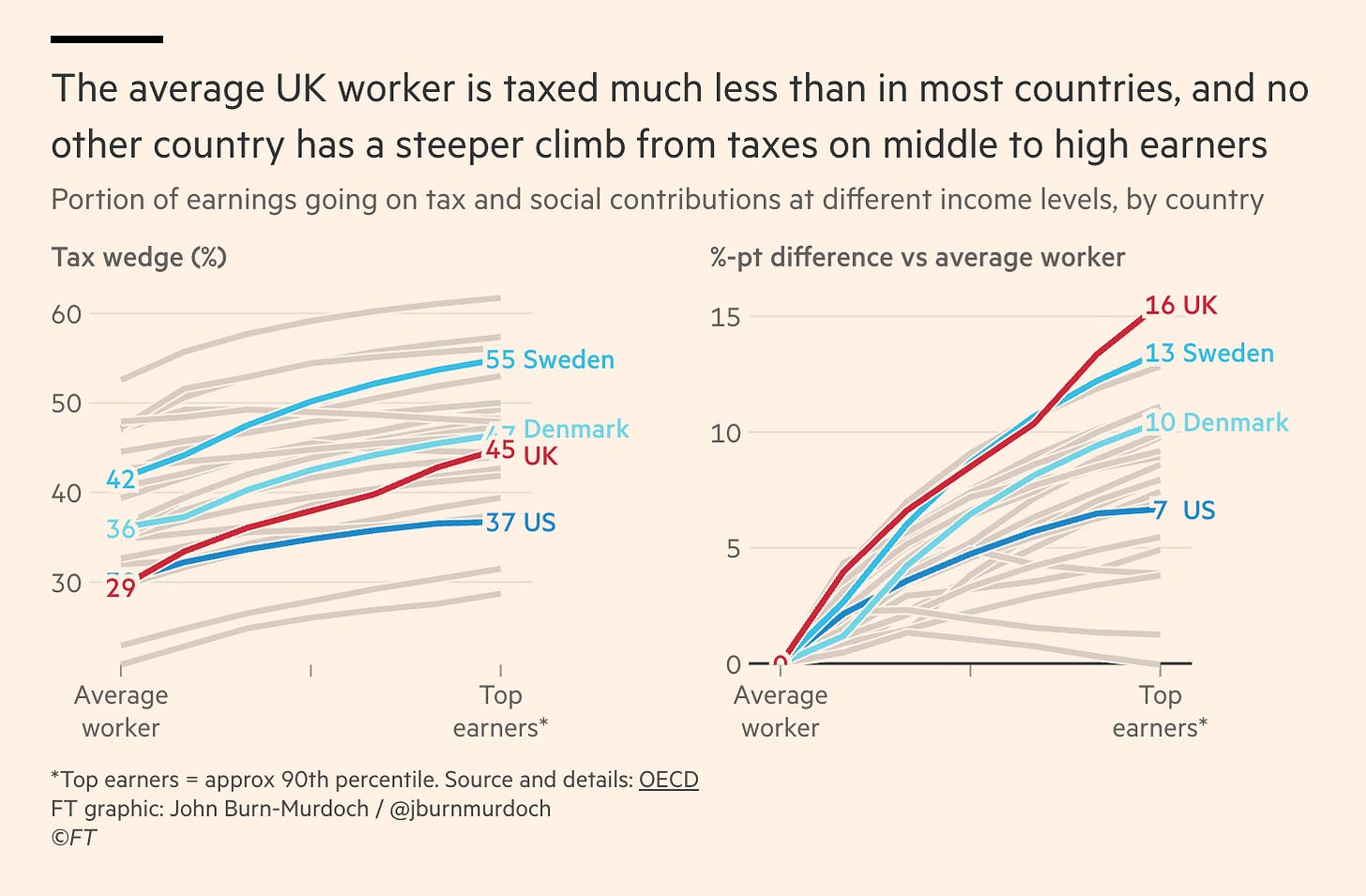

One worry I have with that sort of approach is that, as the FT’s John Burn-Murdoch laid out in a great pre-Budget piece, Britain actually already has a tax system that, if anything, under-taxes the middle classes and over-taxes the rich. (At least compared to other similar countries.)

11. The motor-tax landmine

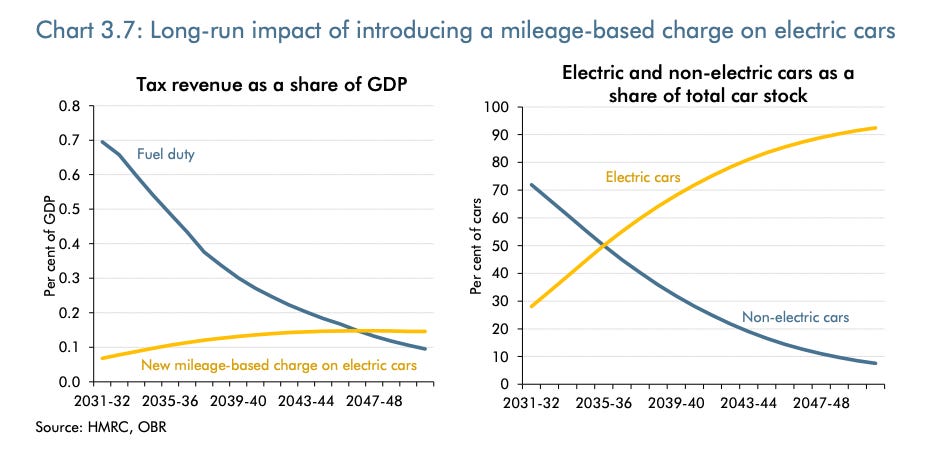

The new tax on electric cars was, as I mentioned above, good news. But Britain still has a huge issue coming: fuel duty is actually a decent-sized tax, despite this and prior governments’ habit of constantly promising to un-freeze it and then failing to deliver.

As EVs proliferate, that tax base goes away, and motoring in general will get cheaper relative to other forms of transit. The new tax will need to be quite a bit higher to make up that gap, and stop the appearance of an inadvertent subsidy for driving (perhaps a fair one, since EVs are less polluting than gasoline cars, but one that should be discussed and not happen invisibly.)

12. The wrong way to discusss inflation

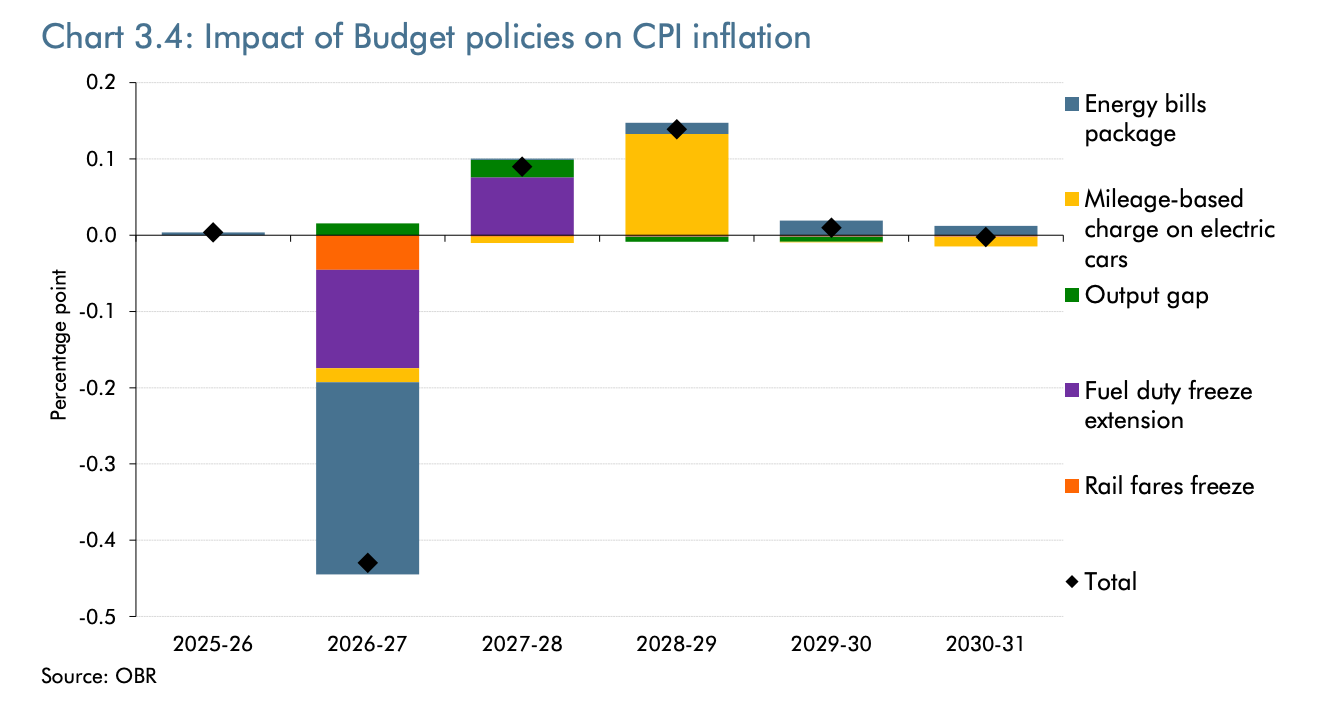

Another complaint of mine that extends well beyond this Budget is how British politics discusses inflation: far too much focus on one-off bodges to administered prices to manipulate the headline rates, far too little on the overall stance of fiscal and monetary policy—which actually determines where inflation lands in the long run.

There was plenty of that in this budget, but I just wanted to highlight this peculiar chart. Conveniently, the inflation impact of this budget is highly negative in the immediate future when some energy bill giveaways land. I’m sympathetic to the notion that the politics of affordability are difficult, and politicians need to be seen to be doing something. But entrenching the notion that inflation can and should be dealt with by the government fiddling with prices is a real problem.

13. The absences

I won’t re-hash my tax policy wish list. As it happens, it is (boringly) not too far off from this joint report from a range of think tanks (and several friends of mine) laying out a cross-party agenda for tax reform.

Safe to say, like last year, there was pretty much nothing in this budget in the way of meaningful growth-boosting reform. I’m a touch more bearish than the consensus in Britain on how central tax problems (vs wider regulatory problems) are to holding back British growth, but the lack of effort is pretty unforgiveable.

Labour could, maybe just, have argued last October that they had a big fiscal hole to fill and didn’t have time to take stock of the right reforms before their first budget. More than a year later, they have no such excuses.

14. “Unprotected departments”: Jeremy Hunt redux

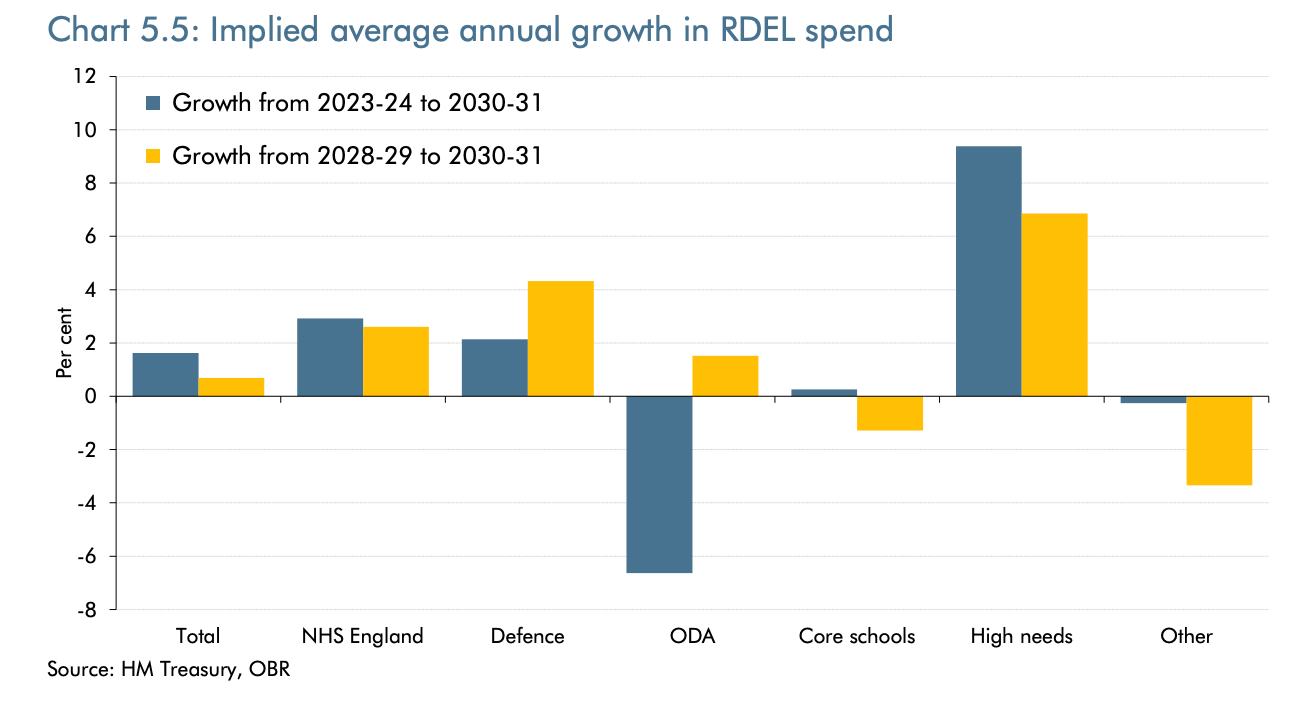

Another bit of Jeremy Hunt nostalgia in the budget was the return of cuts to “unprotected” departments. Because department-by-department spending is allocated less frequently and less far out than the overall “envelope” of total spending planned by the government, opportunities arise to pencil in long-term cuts to flatter the aggregate numbers. Those then, almost invariably, get massaged away before they really happen by raising short-term spending and pushing restraint further into the future.

The last few OBR reports on Conservative budgets always had charts like the one below, making the point that if once you incorporated all the government’s department-by-department commitments, there was not enough money left to fund everything else (unsexy bits of spending like policing, courts or local government) without cuts. We’re now seeing the same dynamic from Labour, with probably-undeliverable spending cuts now provisionally laid out for some departments after the next election.

15. Under-the-radar squeezes

And finally, the OBR has helpfully called out a few of the most potent fiscal landmines affecting the British state. Getting a grip on the cost of asylum and special-needs schooling in particular is tough but vital. Expect those issues to recur.

Another corollary of doing this quickly: I’ve endeavoured to get things right, but may well have botched something. My error bounty stands if you do spot anything.

Two bits of pedantry to note: (a) those numbers are vs Jeremy Hunt’s prior spending plans—and the OBR’s extensions thereof—which have been fairly criticised for being unrealistically tight further out, (b) the tax receipts column also includes the extra tax that comes indirectly from unambiguously good supply reforms e.g. on planning, but the bulk by far is direct effects of tax rises.

Something I would've added is that this Budget refused to allow over65s/Pensioners receive any kind of hit to their finances

Excellent analysis.