One of the joys of running a solo Substack is that I get to valiantly ignore the topic du jour if I don’t think I have much especially novel to add—and so it is with tariffs, with the exception of one chart that I’ll put at the bottom of this post.

So instead, enjoy a Sunday-afternoon screed on British fiscal policy.

Lots is broken in the British economy, and there’s plenty to be breathless about (don’t get me started on VAT exemptions). But today I wanted today to write about the reverse: something which inspires endless anxious hyperventilation, but I’m increasingly convinced is essentially fine and well-functioning—Britain’s fiscal policy process and the role of the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR).

That doubtlessly sounds like the makings of a dull post: taking an already-dry topic and arguing for plodding incrementalism. So to perk things up, I’ll start with a few examples of publications and writers who disagree with me, and find the status quo somewhere between maddening and untenable.

And I’ll conclude with two problems with the fiscal framework that I do see, and suggest some tweaks that would help fix them.

Here’s Chris Giles in the FT (who, as I’ll get to later on, is half-right):

Here’s the Labour backbencher Jonathan Hinder MP (speaking, if I had to guess, for quite a few in the party):

Here’s the journalist and podcaster Lewis Goodall on Twitter:

And here’s Stephen Bush, also of the FT, in a back-and-forth with me on BlueSky when I test-drove this take a few days ago.

To an extent, everyone I’ve flagged here has a point. Virtually every budget (or quasi-budget like the Spring Statement last month) is jam-packed with absurdities. I’ve spent plenty of time grousing about them myself.

A quick primer on how Britain now does fiscal policymaking for any readers who don’t follow this stuff but—generously if inexplicably—have still come this deep into the post. If this stuff is all familiar then do scroll on.

Big tax-and-spend changes get announced at ‘fiscal events’, the tentpole one being the government’s annual Budget. Accompanying those events is a multi-year forecast from the OBR, which takes the government’s current policies, projects how much they’ll cost, projects how much tax revenue to expect and, as a result, projects how much the government will need to borrow.

Chancellors set themselves ‘fiscal rules’, publicly-stated constraints (mainly directed to keeping the bond market on side) stating how much they’ll allow themselves to borrow, based on OBR forecasts. Rachel Reeves, the current chancellor, has two:

The ‘stability rule’, currently the binding one, requires that day-to-day spending should be paid for by taxation by the 2029/30 April-to-April fiscal year (that will shift to three years forward from 2026/7 onwards, and move to allowing a deficit of up to 0.5%).

The ‘investment rule’, which doesn’t bind right now, requires that a convoluted cousin of public debt (public sector net financial liabilities—government debt and liquid financial assets or liabilities), be falling in 2029/30, but also shifting to a rolling three-year horizon from 2026/7.

Those rules bind politically (backing out of them is embarassing, and would prompt an unhelpful bond market reaction) rather than legally, unlike for instance Germany’s debt brake. Bear that in mind whenever reading anything about how a chancellor was “forced” by the OBR into doing something.

The main quantity that fiscal-watchers obsess over is ‘headroom’, how much space the government has against its binding rule—which, if it widens, gets treated like a piggy-bank for spending rises or tax cuts. Given how volatile many of the inputs into headroom are, especially market variables (gilt yields, gas prices, stock prices etc), headroom can have a slight random-number-generator quality to it.

Ample absurdities

A favourite trick of the last chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, was to pencil in big cuts at the back-end of his spending plans and jam the front-end, including the run-up to the last election, with tax cuts and other goodies.1

This time around, the back-and-forth between the government and the OBR about exactly how much its welfare cuts would save was similarly unedifying, as I narrated in a recent piece.

After weeks of rows Liz Kendall, the welfare secretary, promised Parliament that her cobbled-together reforms would save £5bn ($6.5bn) a year. Unfortunately the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), Britain’s fiscal watchdog, reckoned she had over-egged the savings by a billion-plus. Cue a hasty rejig and even deeper cuts.

Richard Hughes, the OBR’s boss, is quietly scathing. “Agreed deadlines were missed,” he says. “It wasn’t accompanied by the usual kind of economic analysis that we would expect.”

Rachel Reeves has also continued some of her predecessors’ worst habits, like forcing the OBR to base its forecasts on a never-to-be-delivered rise in fuel duty. (Governments repeatedly promise the yellow/blue lines, then deliver the black line).

Indeed, the entire pantomime of the Spring Statement, initially billed as a low-drama Spring Forecast, came about because higher interest rates squeezed away the chancellor’s fiscal headroom and forced a round of spending cuts. Or, in other words, because the OBR’s forecast boxed Reeves into delivering a set of cuts that she hadn’t previously seen as necessary.

Altogether, none of that screams stable and functional.

And yet…

A pretty common disease in British economic commentary—and one I’ve succumbed to fairly frequently myself—is to conflate aesthetic problems with substantive ones2.

Wrangling over an effectively-random margin of headroom looks and feels like an unprofessional way to run fiscal policy. So does building castle-in-the-sky sets of tight fiscal plans which never actually get delivered, blooming the deficit instead. And, from the perspective of someone who writes about this for a living, complaining about this sort of thing also makes for tremendously satisfying copy. (An incentive not to be underrated…)

But, zooming out from the micro-level silliness, does the system as a whole spit out reasonable decisions?3 The key test, for me, is whether the system adequately encourages politicians to belt-tighten if circumstances demand it, for instance if interest rates rise appreciably.

To start, we can see how politicians have responded to changes in OBR forecasts since its founding in 2010. Have worsening, or improving, background conditions prompted sensible shifts in behaviour?

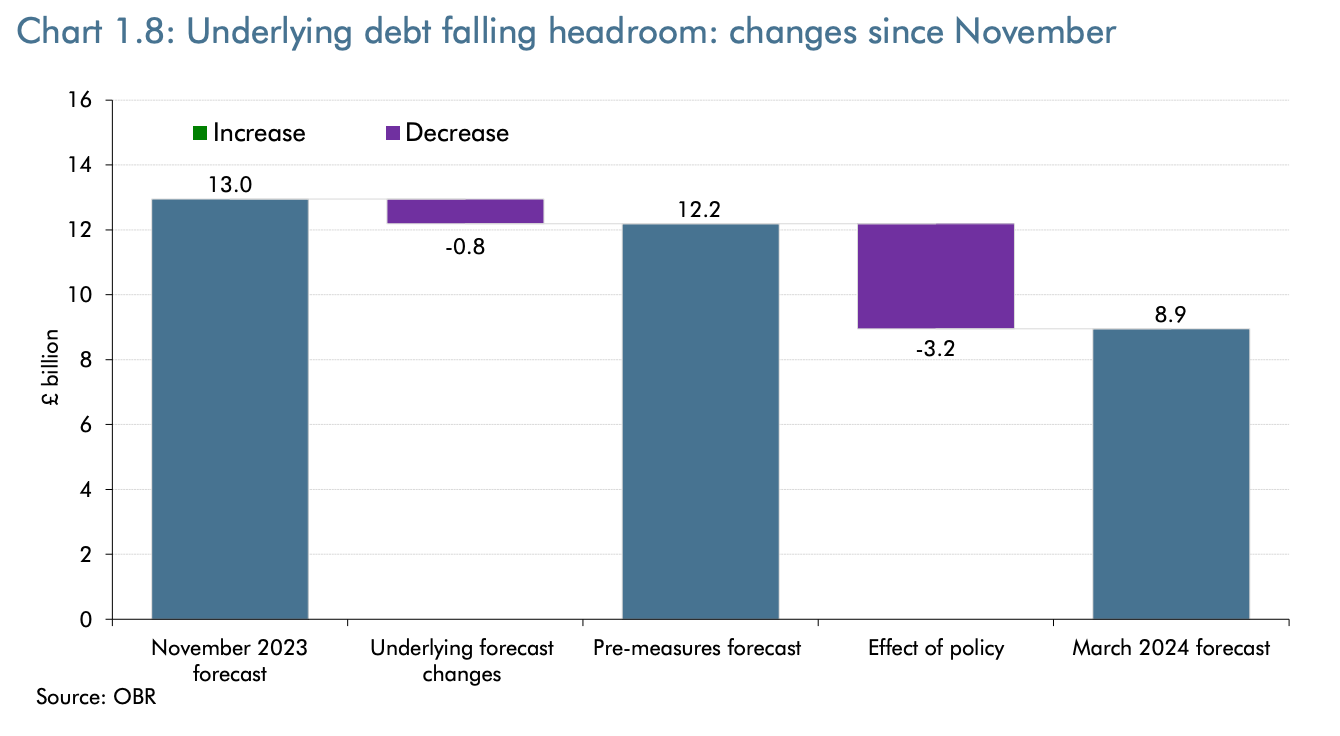

I’ve tweaked a chart that the OBR produces on this below, which I find pretty useful in laying out what’s going on—you can see that when forecasts shift, the politicians’ response is almost always at least in the right direction (i.e. tighening policy when forecasts worsen, the red box, and loosening it when they improve, the green box). Unsurprisingly, particularly with worsening forecasts, the policy response tends not to fully offset the forecast move (nor, given the uncertainty in these forecasts, is it clear that’d be desirable).

That perspective is a pretty charitable one, to be fair. A different presentation of the same data from the IFS reveals some deeper issues. Proportionally, politicians under-respond more to worsening forecasts than improving ones (i.e. they’re happier to bank the gains than feel the losses—that’s the relative size of the black and green bars). And there is a real issue with Hunt-style promises of future restraint that never actually materialise. Even when forecasts deteriorate, the response is often to loosen fiscal policy for at least the first few years.

So clearly, the current system does leave some bias towards running deficits. But eliminating short-termism in fiscal policy altogether is something that’s pretty much impossible to crack. And to a more-realistic standard of keeping that deficit bias partly in check, the current fiscal framework seems to perform decently.

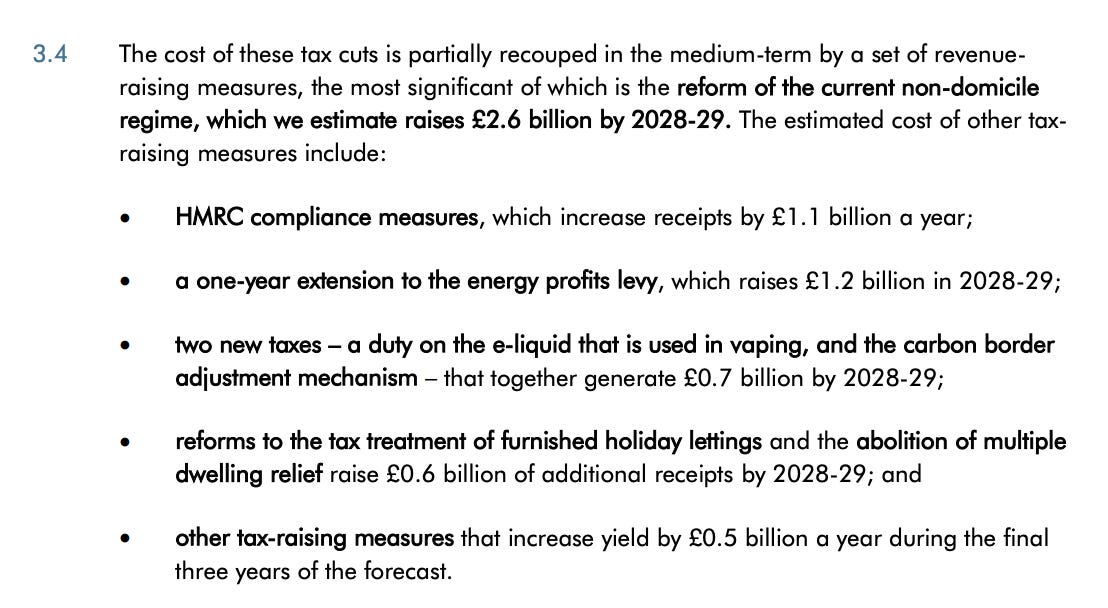

One helpful worked example here is the final budget before the last election. Jeremy Hunt had already delivered a big dose of tax cuts (2 percentage points off national insurance) at the previous fiscal event, the Autumn Statement in 2023. 2024 was clearly set to be an election year, and so the political logic for another round of tax cuts was pretty airtight. Sure enough, that’s what Hunt delivered, cutting another 2 percentage points in the March 2024 budget, delivering a total of £20bn/year or so in tax cuts.

But, his fiscal headroom turned out to matter rather a lot. Because the underlying forecast hadn’t changed very much and he was already running close to the limit of what his fiscal rules would take (gilt yields had been on a long round trip between the two fiscal statements, ending up in a similar-ish place), those cuts ended up being mostly offset by tax rises elsewhere.

The OBR lays that out in the bullet points below. Even when the political logic for tax cuts was overwhelming, the fiscal framework forced a reluctant chancellor to mostly offset them with increases elsewhere.

And, of course, Hunt’s 2023/4 National Insurance cuts were de facto reversed (albeit in an inefficient and distortive way) by Reeves’s post-election increase to employer’s national insurance. In an ideal world, cutting taxes before an election and raising them right afterwards would be verboten full stop. But as a second-best solution, having a framework that rewards backpedalling on that sort of silliness works well, too.

So on the big-deal questions of how much the government borrows and spends, despite a spectacularly ugly mechanism for arriving at its decisions, Britain’s fiscal framework seems to split out plans that are at-least-OK.

One of the biggest outstanding issues in the fiscal setup is also soon to get mostly-fixed by some changes that Labour has already made. The fiscal rules are moving towards binding on a three-year horizon and the government has committed to running spending reviews more regularly, meaning that the implication of those further-out forecasts will actually get spelled out for departmental budgets. That should make it appreciably tougher for chancellors to indulge in the Hunt-style fiscal fiction of cramming spending cuts into forecast years four and five while offering bread-and-circuses in years one, two and three.

OK rules, bad policies?

There is a second critique that’s also worth spending some time on, though: that even if the aggregate outputs of Britain’s fiscal system are OK, that it incentivises bean-counting policies that are calibrated to keep the OBR on side, not actually deliver the best outcomes. The latest example of this is the welfare cuts that I touched on above, which had to be deepened at the last minute because the OBR was sceptical of how much they would save. (The less-thoughtful version of this claim is just to assert that the “OBR is too powerful”, because government is altering policy in response to its forecasts.)

At some level, even if that is happening, it’s probably fair just to blame the government of the day. Those fine-margin calls only matter if, irresponsibly, they leave too little headroom—as Reeves has at the moment.

On the specific issue of the welfare cuts4, there was also a basic governing competence question: no-one forced Reeves, Liz Kendall, and co to wait until the last minute to hash out their plans5. Britain’s issues with a spiralling working-age health-benefits bill have been apparent for a while, as I ranted about in a leader article for The Economist a few weeks ago.

The noblest traditions of modern British policymaking were followed. First came dithering: worklessness from ill health rose sharply after the pandemic, but it was 18 months before Rishi Sunak’s government took a stab at tightening benefits in response. By then, around 1m people of working age had fallen out of the labour force since 2019, mostly because of supposed poor health. His changes ended up being blocked by the courts—the consultation was deemed insufficiently thorough—though not before a looming election gave an excuse for further delay. Labour won, and chose to procrastinate with a new long-term target: to get the working-age employment rate to 80%, a level Britain has never hit.

Eventually, two things concentrated minds: a genuine need to make room for higher defence spending, and an artificial crisis. Rachel Reeves, the chancellor, had left too little fiscal leeway in her budget in October. What was supposed to be a routine economic-forecast update on March 26th has turned into a scramble for cash. Because Ms Reeves was in danger of breaking her self-imposed fiscal rules, finding money from welfare cuts suddenly became urgent. At last Britain decided to take a proper look at worklessness and the welfare system.

Still, blaming the government entirely is probably one notch too harsh—after all, governments make decisions on headroom in response to the incentives that the current system creates. Right now, those incentives are mostly to squeeze out as much borrowing as possible while staying just on the right side of the fiscal rules.

But criticising policy changes made to “please the OBR” also ignores the counterfactual risks on the other side. I see several. To start, having an OBR analysis insulates the government from wishful thinking. Many Tories probably overestimate the growth benefit from tax cuts, many in Labour likewise overestimate the impact of public investment. Governments can (and probably should more often) lay out their disagreements with the OBR, but without that layer of accountability, the temptation to over-egg how beneficial a policy was likely to be (and thus miscalibrate its scale) would be vast.

Another is to avoid being blind to tradeoffs. Take, again, the health-benefit cuts. Perhaps parts of that reform were intended more to save money than to tackle Britain’s worklessness problem. But the right comparison is not against not making those cuts at all, but—in the context of the government’s fiscal envelope being constrained by largely-reasonable fiscal rules—against whatever would have been cut instead. Having a flinty-eyed OBR that forces the government to crystallise those tradeoffs is a good thing.

And, one final point that’s worth stating explicitly. Britain’s choice is not about whether government borrowing gets hemmed in at all, but whether that happens inside the fiscal-policy process—through something like the OBR—or implicitly through a complaining gilt market. Pretty much everyone who has issues with the current setup would be far more horrified if the bond vigilantes were at the wheel.

A few fixes

That’s not to say that everything is perfect. I see one big and one medium-sized problem with how Britain does fiscal policymaking.

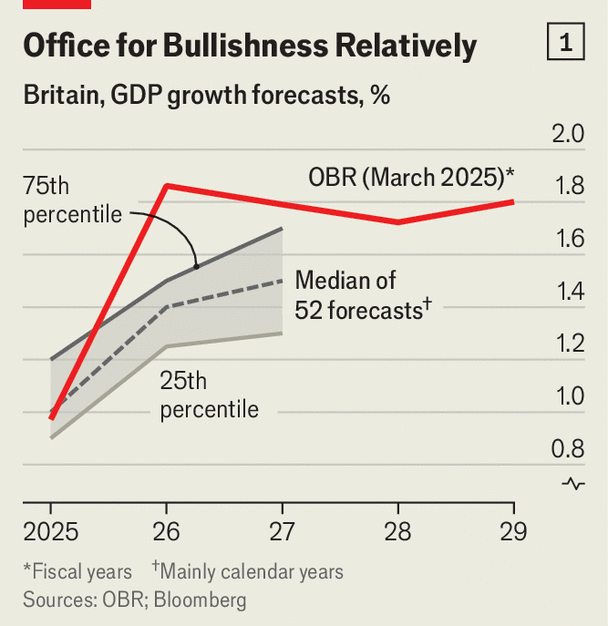

The big one is the OBR’s macroeconomic forecasts, especially of GDP growth. These are ultra-influential for the government’s overall fiscal position (small tweaks could easily block or open up tens of billions in borrowing), so any moves downward tend to be extraordinarily controversial. The result, unsurprisingly, is that the OBR’s forecasts have consistently been too optimistic.6

That remains the case today—at least compared to other forecasters (who, in fairness, generally tend to look over a shorter horizon than the OBR).

The obvious problem is that this leads to fictitious forecasts, where even if governments stuck to their promised fiscal stringency—which, of course, they never do—slow growth would ensure that debt-to-GDP keeps creeping up.

But the still-bigger issue, which Britain is confronting now, is what happens when the forecasts need adjusting. The political incentives for the OBR will always lean against downgrading, given the risk of an unpleasant backlash. That means that whenever a downgrade is actually mooted, like today or in 2017, it’s already happening much too late and can’t be gradually eased into. That gives the fiscal process an unnecessarily sharp jolt.

Instead, the OBR’s should operate under a strong presumption that its core macro forecasts track market consensus. Financial markets are the best social technology we have for generating predictions about the future, we’d be silly not to use them more. Given the OBR’s goal is to make the government’s fiscal plans credible to the market, operating off the same macro baseline would be a helpful move in that direction. Removing discretion from core growth and inflation assumptions also prevents the sort of counterproductive Westminster guessing-game we’re in at the moment over whether the OBR will pull the trigger on a forecast downgrade.

Practically, what would that look like? I’ll hopefully write more at some point on precise specifics, but on growth for instance that’d mean some combination of: tracking consensus 2-3 year forward GDP growth from a panel of market forecasters (which the BoE already does), issuing GDP-linked bonds or similar securities that would explicitly price out an implied path for growth at different tenors (like the linkers market already does for inflation—that’d be the most compelling approach to me), or proxying out implied long-run growth from the pricing for earnings growth of domestic-facing equities.

There would still be some space for discretion, and the OBR’s models would still be needed to split out a headline GDP growth number into productivity growth, population growth, labour utilisation and so on. The OBR would also still need to evaluate the growth implications of not-yet-announced policies and fold them into the forecast, at least for one fiscal event before the market has time to digest them. But for the most part, the process would be much more mechanical.

You could imagine something similar on inflation, using inflation-linked bonds (which now have 40+ years of data on in Britain), perhaps alongside inflation-expectations surveys. There’d have to be some adjustment for the long-running distortion to UK breakeven inflation numbers from the scale and inelasticity of pension-fund demand, but making and monitoring that tweak should be far easier than generating a full inflation forecast.

Shifting towards that setup right now would be akin to a sharp one-off forecast downgrade (given how far above consensus the OBR now is), but there’s no reason that couldn’t be phased in over five or ten years to smooth over the shock.

(Another option, which the FT pitched a few days ago after rightly flagging the OBR’s macro views as a problem, would be just to hand the macro side of forecasting back to politicians. That strikes me as bonkers—all the same incentives for over-optimism will be even stronger, and any time the forecast needed to be downgraded the chancellor would be accused of ‘doing the country down’. Having politicians own a problem isn’t much consolation if you also make that problem bigger by handing it to them.)

Then, the medium-sized problem: a mismatch between the number of forecasts and fiscal events. Having a system that boxes the chancellor in to delivering a budget purely because of forecast shifts is clearly foolish. That wouldn’t be a problem if Reeves had left more headroom, but the system should be resilient even to chancellors like her who skirt the edges of their rules.

There are two pretty straightforward solutions. The first would be to get rid of the requirement for there to be two forecasts a year at all. If the chancellor wants to commit to only holding one fiscal event a year, accompanying that with a single forecast seems entirely fair—perhaps with an added provision for a forecast re-run in the case of genuine emergencies.

The second would be to simply let the chancellor look through minor fiscal rule misses outside of set-piece Budgets. Could Reeves not, as Tom Pope at the IfG among others has suggested, simply have said that if headroom was still a problem in the autumn that she’d fix it at the Budget then?

Fixing both issues would knock out the most obviously-perverse features of Britain’s fiscal system.

It still wouldn’t be perfect; politicians will always be tempted to over-borrow. But what Britain has right now, for all its visible absurdities, works much better than its many critics admit. Don’t call it ‘world-beating’, but compared to America’s spiralling deficits or ‘superbonus’ mess in Italy, Britain could have it far, far worse.

And on tariffs…

Grasping the sheer number of strands in the tariff story—crashing global stock-markets, the dollar’s retreat as a safe-haven asset, recession fears, etc.—is tough.

But there was one that I did want to pull out: the human welfare implications in low- and middle- income countries. The most-tariffed countries pretty much all have a GDP per capita of $15,000 or below.

Lots, like Bangladesh or Cambodia, are prototypical manufacturing-development success stories (hence running a goods trade surplus with the US, and hence falling in the crosshairs of the White Houses’ dubious tariff calculation).

Trump II proving a disaster for the US is disappointing, but not hugely surprising. The sheer extent of harm to the world’s poorest has been, though.

Add up the tariffs, all-but-abolishing USAID (and—though Keir Starmer is mainly the one to blame here—leading Britain to similarly gut its bilaterial aid function), and the global health implications of pulling so much scientific research funding, and you end up in a pretty ghastly place for global poverty. Outside wartime, I can’t think of another American presidency that’ll have quite so explicit a death toll attached to it.

A slightly more nuanced version of that trick is a kind of reverse version: yanking tax from the far future into the nearer, fiscal-rules-relevant future. Hunt pulled that one in the March 2024 budget, by cutting capital gains taxes on second homes and claiming that it was Laffer-compliant—a tax cut that actually raised revenue. But that was only true because it pulled forward tax revenue from the future into that critical 5-year point for Hunt’s fiscal rules, and actually reduced aggregate receipts from the tax overall.

This is everywhere—think, for instance, about all the bits of insanity (like wacky marginal rate schedules) in the British tax system. But, and I’ll write more on this soon, I worry that this sort of thing gets somewhat over-covered relative to the actual economic damage it causes because it’s so aesthetically infuriating. (And conversely, that the economic damage of logical-but-bad taxes like stamp duty, which back-of-the-envelope feels much greater, gets underplayed. Plus, of course, the fact that poor tax design, annoying as it is, surely has only a middling rank on the list of things holding back the British economy overall.)

Of course, during moments where you may want fiscal policy to be activist—for instance in stimulating during an especially-deep recession—the sign flips, and a worsening forecast may actually mean you want government to borrow or spend more. You get a version of this critique from Anatole Kaletsky (from this paywalled piece).

But:

During the serious growth scares that have started while the OBR has been around, Covid and the ‘22 energy shock, governments have been demonstrably pretty willing to pull the fiscal lever.

This is precisely why fiscal rules tend to be much more flexible about next-year versus steady-state borrowing.

This underplays the value in maintaining stable and restrained fiscal policy during normal times (and under those circumstances using the monetary lever to manage the economy cycle), especially for an economy like Britain’s which relies so heavily on borrowing from foreigners.

I disregard here the actual most common reason for complaints about the OBR’s role in the process, which are just sublimated objections about the fact that welfare is getting cut at all—especially from Labour-sympathetic types who would rather pin the cuts on an unaccountable Quango than a Labour government. My own view is that worklessness had become a slow-motion disaster and delivering much less in cuts than what the government eventually did would have been vastly irresponsible. More on that from me here.

I put the question of “will the £5bn/year in savings that Kendall has announced fall afoul of the OBR” to a couple fiscal-policy wonks the afternoon after the announcements. The tenor of response generally was that “there is no way they’d have announced those figures without getting the OBR fully on board first”. That, as it turned out, ended up being rather too generous a read of how well the process was run!

There’s a genre of response to the OBR’s forecasting issues, like this report from UK Day One, that are simultaneously full of good ideas and missing the point. UK Day One argues that the OBR needs more cash (agreed!) and deeper connections with frontier academic macroeconomics (agreed!). That’s totally sensible, but mistakes the OBR’s forecasting problem for a technology one (they need better models) rather than an institutional one (the political costs of a downgrade are higher than the costs of an upgrade). The right answer here needs to tackle, or hive off, those skewed incentives.

Great article, thanks for sharing.

I'd be interested to know more about the extent to which the gilt markets sensitivity to increased borrowing at recent fiscal events is independent from the govt. fiscal rule / OBR forecasts interplay. I.e. did gilt yields go up at the autumn budget because Reeves had little 'headroom' against the OBR forecast, or because the gilt market fundamentally reassessed UK sovereign risk.

Also, I'd be interested to hear your thoughts on how the govt. could incorporate more public sector net worth metrics in statements / if you think that is worthwhile. It strikes me that while not a silver bullet PSNW ideas are sorely neglected at the moment, considering issues like the public sector pension liability, infra investment contributing to deficits w/o being captured as assets etc. etc.

Thanks

Leo