Pick any blue state in America. Massachusetts, maybe. As a rough approximation of the British economy, you could do a lot worse than just thinking of it as Massachusetts with worse GDP growth.

The analogy isn’t perfect—Massachusetts didn’t do Brexit—but lots of the themes are pretty similar: increased reliance on high-value services, well-meaning but heavy-handed governance, disproportionate influence of a superstar city (that may be a charitable way to describe Boston), and a painful reliance on generations-old housing and infrastructure that’s getting more rickety by the year.

So British readers ought to pay attention to the post-mortems about Democratic governance in America that have started to emerge after November’s election. Plenty of lessons should be able to quite straightforwardly cross the Atlantic.

A few weeks ago, I reviewed two books in that vein for The Economist, ‘Abundance’ by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson, and ‘Why Nothing Works’ by Marc Dunkelman. That piece (you can read it here) focused on how the books were intervening in the American policy debate. On that, I landed in a pretty positive place.

On economics as well as politics, therefore, the left must work out what has gone wrong. Two new books—“Why Nothing Works” by Marc Dunkelman of Brown University and “Abundance” by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson, a pair of journalists—suggest an answer: that excessive regulation has hurt America by blocking housebuilding, infrastructure and innovation.

…

Nowadays “You could have Robert Moses come back from the dead and he wouldn’t be able to do shit”.

The argument that excessive regulation has choked housebuilding, ruined public transport efforts, and jacked up electricity prices is hardly a novel one in Britain either. Britain’s current government (over-generously, I think) argues that tackling such issues is its animating theory of economic growth.

But there are some instructive differences in how Abundance as a political and economic agenda works in Britain compared to America, and I thought it’d be valuable to parse those out.

One note: Here, I focus on ‘Abundance’. But I really would recommend Marc Dunkelman’s ‘Why Nothing Works’, and reckon it’s, if anything, the more interesting of the two books. Much like how the evolutionary pressures of the ocean floor favour crab-like anatomy so powerfully that the crab’s body plan has emerged independently at least five times—the failures in American liberal governance are sufficiently striking that Dunkelman, who starts with quite different intellectual and historical influences to the ‘Abundance’ crowd, alights on a similar-ish diagnosis. But by taking a different route to get to a nearby, though not identical, destination, ‘Why Nothing Works’ carries a refreshing novelty.

Britain’s Politics of Abundance: A National, Not Partisan Failure

A striking feature of ‘Abundance’ (the book) is quite how explicitly party-political Democrat it reads. Partly, that’s a deliberate over-compensation. Proposing an agenda of deregulation to American liberals will inevitably raise hackles; leaning hard into the progressive language helps sweeten the pill. Besides, Klein and Thompson are themselves on the left, as they stress repeatedly, and see their role largely as taking a side in the intra-Democratic debate. The passage below, from early in the book, was pretty forceful in that respect.

We are both liberals in the American tradition. The problems we seek to solve are mostly problems that exist within the zone of liberal concern. We worry over climate change and health inequality. We want more affordable housing and higher median wages. We want children to breathe cleaner air and commuters to move easily on mass transit systems.

…

There are people seeking complementary reforms in that [right-leaning] coalition, such as James Pethokoukis, author of The Conservative Futurist; the economist Tyler Cowen, who has called for a “State Capacity Libertarianism”; and the array of policy experts organized in the Niskanen Center. We wish them well.

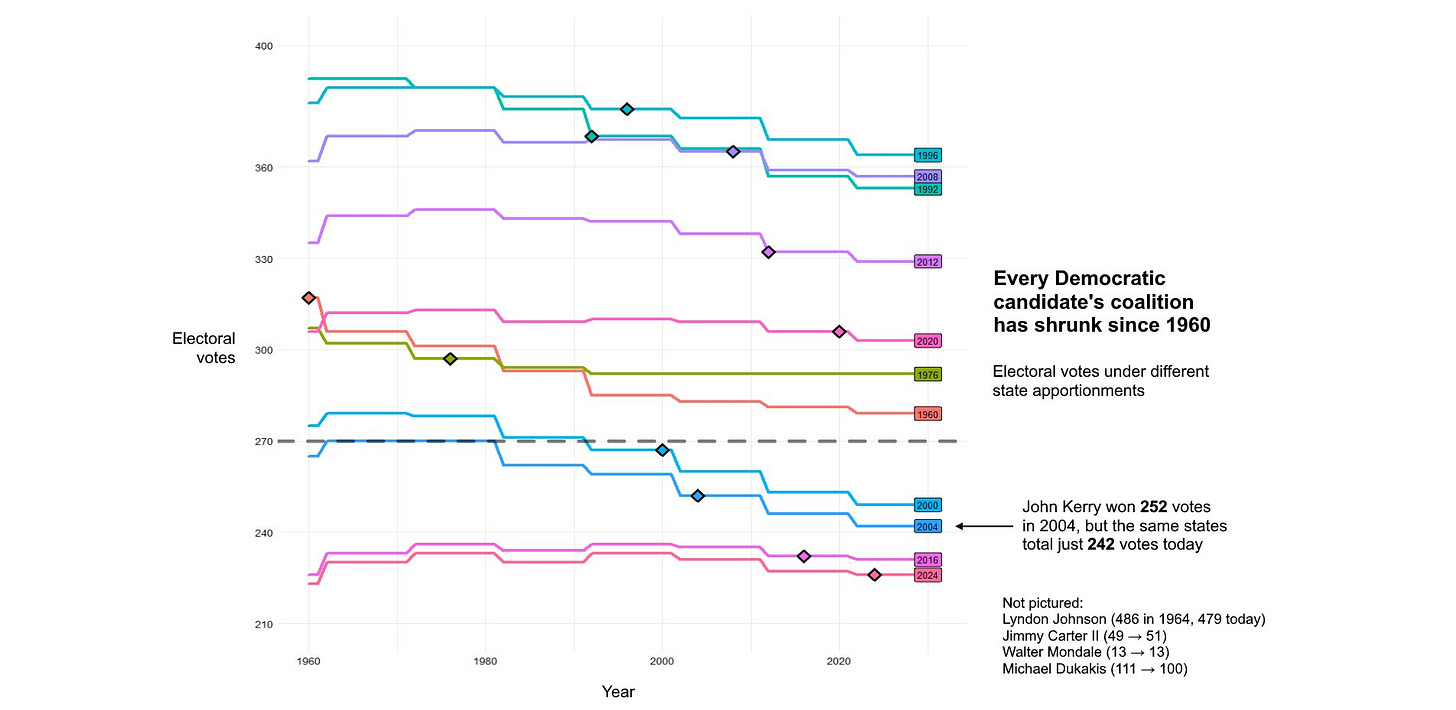

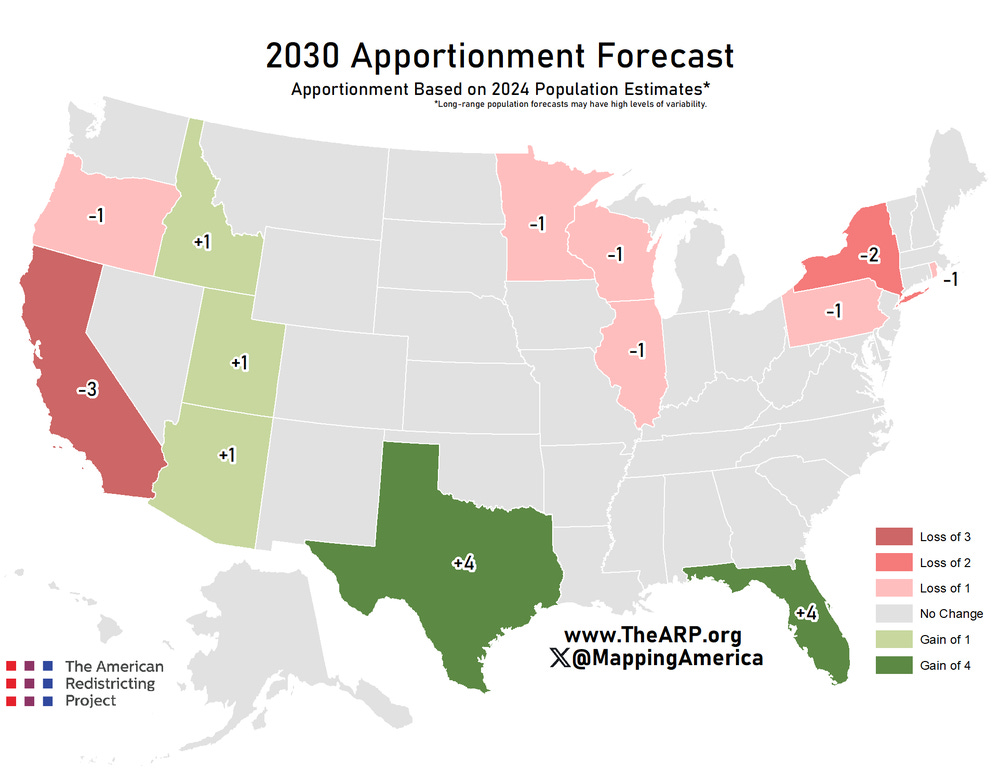

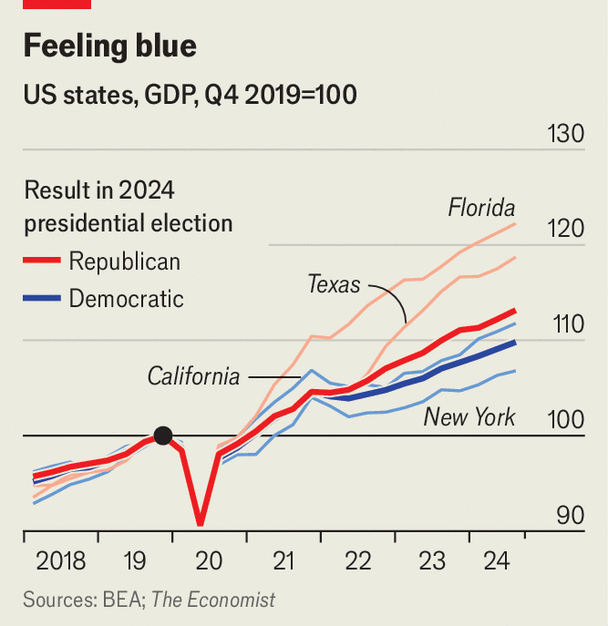

But there’s a deeper reason, I think, why the politics of Abundance so often feel left-coded in America: the stakes are different. If blue states get something wrong, they certainly suffer. At the same time, red states can take a different path, and on issues of housing and energy construction they often have. That dampens the nation-wide economic fallout of constraining the supply-side—housing units that couldn’t get built in Manhattan end up in Austin or Atlanta instead.

The political fallout, though, gets accentuated. If red states out-grow blue ones, both in economic and population terms, that makes issues with progressive governance harder-to-avoid. And internal migration literally saps the power of blue states by reducing their representation in Congress and the electoral college. Most likely, the just-about-possible route to 270 electoral votes that Kamala Harris had by winning Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin will be inaccessible within a few cycles.

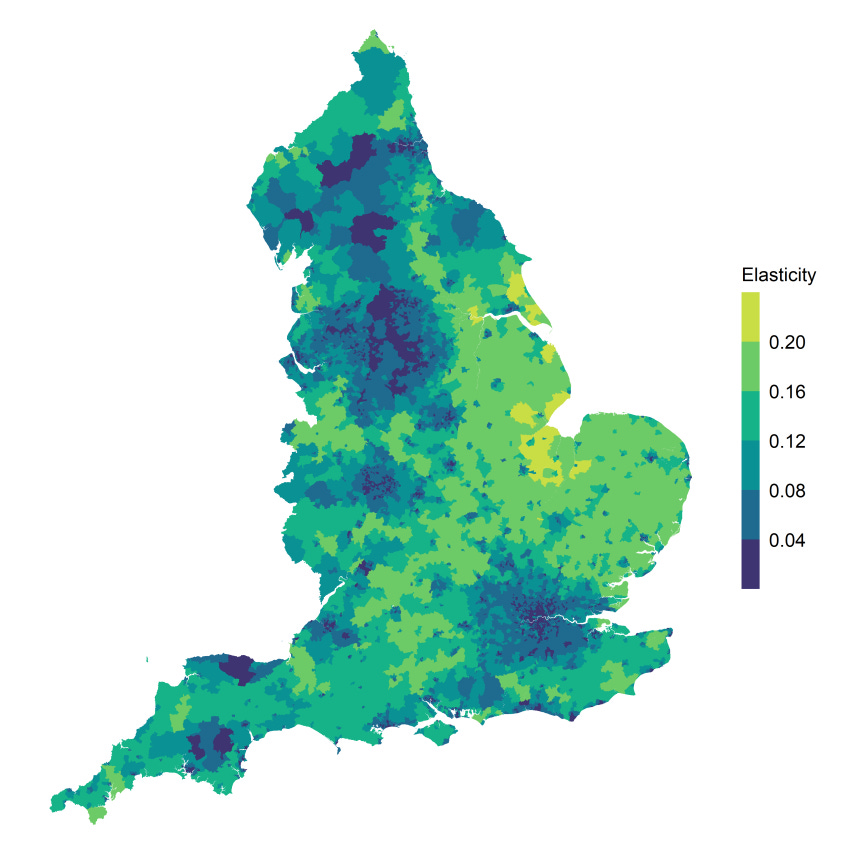

The dynamic is reversed in Britain: the economic trumps the political. Local government certainly has some powers over permitting, but is more constrained (especially on infrastucture) than American states. And the incentives for different regions to act differently are narrowed, too—extra tax raised would largely flow back to the Treasury, but local politicians would still have to face off with angry NIMBYs at the next election. So, the political consequences of anti-Abundance governance are less glaringly visible.

Meanwhile, economic activity that is choked off by overregulation in one place isn’t just displaced to elsewhere in the country, but doesn’t happen at all (or is displaced to another country entirely—witness the legions of Brits decamping to Dubai).

Long-term, I’m pretty persuaded that American-style fiscal devolution to something like the metro-area level (and there is plenty of historical precedent for empowered local government in Britain too) would be sensible. Letting mayors levy taxes to get infrastructure built, rather than going with a begging-bowl to the Treasury, and letting them keep more of the tax receipts from densification, would be an unalloyed good.

But in the meantime, Britain is left with a rather different sort of Abundance politics. The forcing mechanism to start facing down the NIMBYs is less political and more economic—the painful reality of slow growth, which has at last started to bite hard enough that the voting public has noticed. The plus side, potentially, is that the overall Abundance/YIMBY agenda manages to get a little less politicised in Britain, though that may be a fornlorn hope.

Britain’s Economics of Abundance: Socialising the Cost of Scarcity

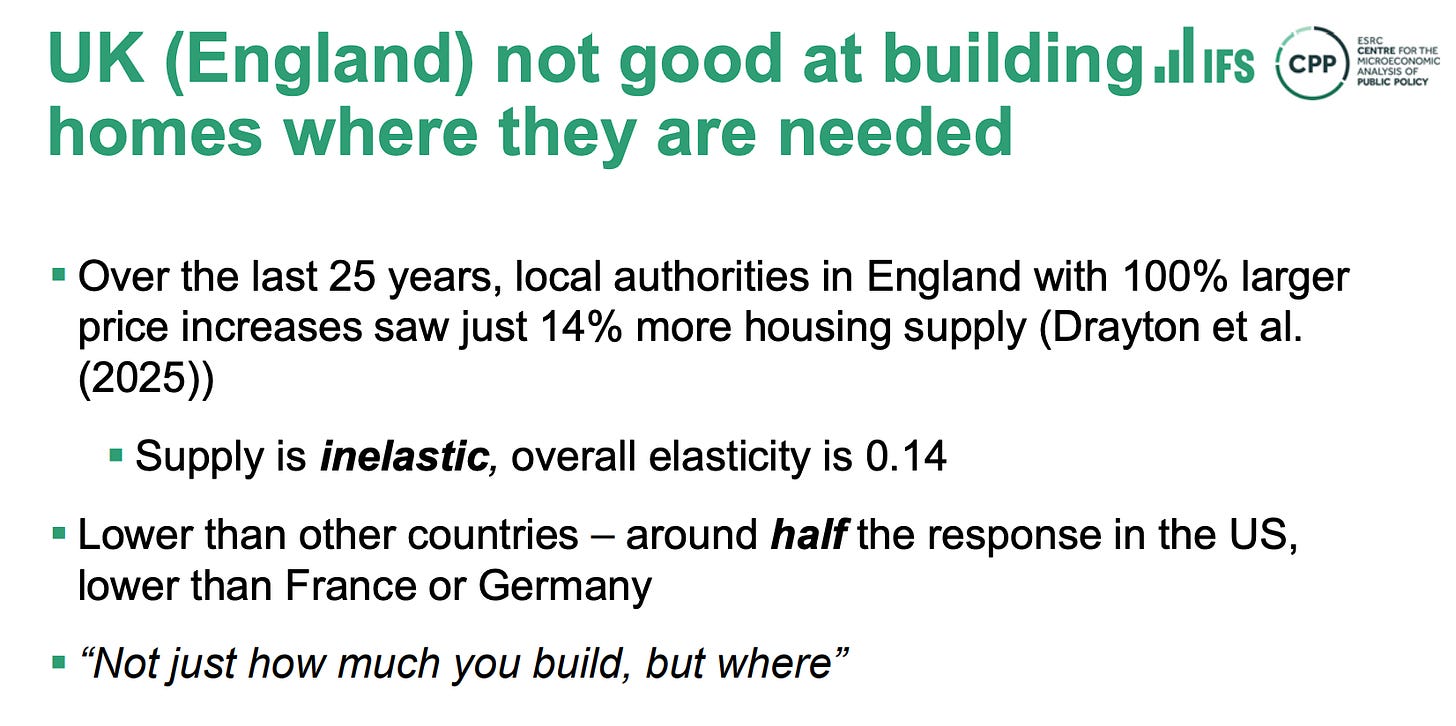

Plenty of the core Abundance alarm-bells of too-high housing and energy costs are going off even more strongly in Britain than America. See, for instance, this great bit of analysis the IFS presented a few days ago (No, wait, come back!). But that’s well-trodden territory, so I wanted to focus on something else.

The core symptoms that Abundance types fret about—high and rising costs of essentials like housing and energy—can have quite painful consequences for government finances in a country like Britain that has a thicker social-safety net than America.

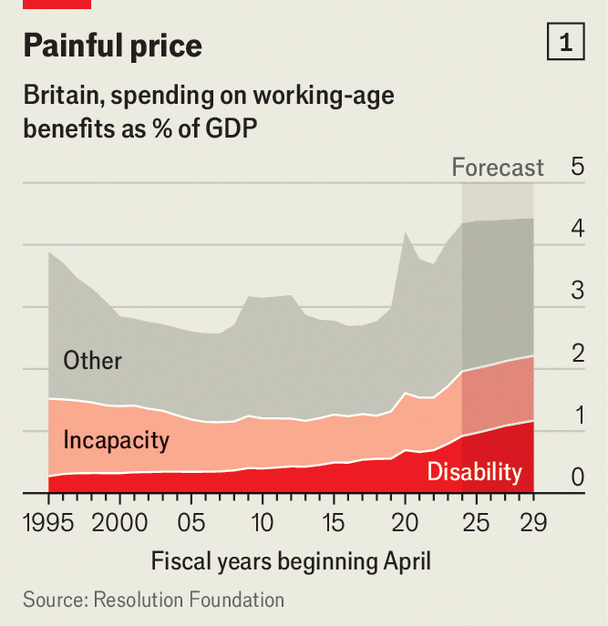

Take the welfare system. Britain is trapped in a particular perversity at the moment where overall spending on benefits (even excluding the state pension) is at record-highs and living standards for the worst-off are still painfully squeezed. (And unemployment is not that far off historic lows). Partly, that’s because of a separate set of issues to do with the over-assignment of health-related benefits.

But another part of the story, I think, is that the high, rising and unavoidable cost of rent and electricity mean that welfare generosity can increase (even in inflation-adjusted terms) without it feeling more generous, since much of the uplift gets eaten up by unavoidable essentials.

That sort of thing sometimes get framed as a broad complaint about the “cost of living”. But those sorts of gripes tend to wind up as ill-directed complaints about inflation in general, or focus on places like food prices, where the issues are different. (On food, competition is doing a good job at keeping prices as low as they can be; the challenge is more about exposure to choppy global commodity markets).

Stepping back, effectively what’s going on is that the higher cost of land and energy is getting socialised across the country by the tax system. And that isn’t just a welfare system story—think of the talented civil servants that the government loses because public-sector salaries can’t match London housing costs; how scarce and expensive prison places now are because of under-building; the scandalous prices that government is paying to house asylum-seekers, and so on.

The effect is a double economic choking. Taxpayers’ own disposable income goes down as a higher share of their spending gets eaten up by essentials, and then their taxes go up too as those same essentials become so expensive that the state ends up subsidising access for a decent chunk of the population.1

All that should, though, make the benefits of housing and energy abundance in Britain even more pronounced, too. Supply-side reform might be the rare policy that not only boosts growth for free, but lowers government transfer spending too.

But scale and ambition matters. And there, I still worry Britain’s current government isn’t being as brave as it could be—as I explained, cribbing a bit from ‘Abundance’ for the Josh Shapiro example, in a leader article this week.

So far, Labour’s best idea for growth has been to build more infrastructure and housing. But flagship projects, like Heathrow’s third runway and a railway between Oxford and Cambridge, will not be finished until the mid-2030s. Contrast Labour’s insouciance with Josh Shapiro, Pennsylvania’s governor, who in 2023 marshalled the full forces of his government to fix a collapsed motorway in 12 days, instead of the expected 12 months or more.

Time for Labour, and indeed British politicians of all stripes, to take the Abundance pill.

Kudos (and thank you!) for getting this far down—I’m playing around with format, and am curious if readers prefer deeper-dive pieces like this one or wider-ranging ones like my last post more. Do send over any thoughts!

I’d love to see some sort of quantification of this effect—something like “how much lower would state spending be if land and energy costs had been flat in real-terms since 1990”, but I imagine it’d be rather difficult and I certainly don’t have the appetite to take it on myself. But, my vibes-based sense is that it probably does matter.

Well, FWIW, to your question, I loved the piece- this "deep dive" is what I am in substack for. It was extremely interesting and information dense. I agree that Labour needs to see that increasing significantly the level of ambition of its currently timid growth agenda is not just right for the UK, but right for itself, narrowly, politically-- a matter of survival. If they let these next 4 years drift similarly as year 1, the UK will be in trouble and they will be wiped out. This "Shapiro timeline" is the one possible path for success they have- the sooner they realize, the better. The UK is centralized enough that taking the relevant decisions is actually feasible. The current timelines are simply ridiculous- and the costs do not come from any law of physics, but from regulation upon regulation that is for the government majority in the Commons to remove if it so chooses.

By the way, on similar notes (concluding instead on how EU politicians SPD/Green should get into the Abundance agenda) our review on Silicon Continent of the book and the agenda. https://www.siliconcontinent.com/p/book-review-abundance-by-ezra-klein

Interesting post. Three, rather boring points reflecting my training as an economists before physics envy took over the profession . First, abundance as the opposite to scarcity (which is how it often seems to be presented) is an economic nonsense: you always need to make choices, the questions are about which ones. Second, fiscal devolution is highly desirable (indeed essential if you want to preserve local government as an independent tier, which I’m not sure this administration does) but doesn’t address the path dependency of regional inequality. Finally, I’m not sure that you can keep land prices down because, unlike capital and labour, it’s fixed in supply by location and is released on a market driven basis. If you own a greenfield site near a big town/city you’re only going to see its value increase if you hold onto it so you’re not going to release it cheaply. You can build more houses this way but it won’t have a significant impact on prices. See the OBR comments for an illustration.