All the ways I was wrong last year (part 1)

A predictions post-mortem, plus yet more on Labour and growth

Hello again—

Thanks to everyone who read the first post and (better yet) subscribed! Watching the numbers move on Substack’s subscribers chart is surprisingly entertaining, even if the actual figures involved are still pretty humble.

For my second post, I thought it’d be productive to look back. My first article for The Economist came out a year ago last week—a piece on inflation and the Bank of England (some things don’t change…). Then, it seemed newsworthy that any rate-setter wanted to cut. Now, even former ultra-hawk Catherine Mann has flipped.

My previous employer ran a political-economic predictions contest at the end of each year (my performances tended to be middling). So I thought it’d be salutary for me, and an interesting window into what was genuinely unforeseeable in 2024, to look through which predictions in my older articles aged like milk and which, if any, like wine.

Further down, there’s also a bit about Labour’s economic growth plans, which have gotten a little less fuzzy since the start of the year, along with the usual links, thoughts, and charts. And one warning: this post ended up on the chunkier side. I’ll be briefer next time.

Where I was wrong last year

One of the perks of now having a job where my main output is takes analysis, not buy/sell views on financial assets, is being able to couch guesses with a bit of plausible deniability. But, despite my better instincts, I did make a few concrete predictions over the past year. For this post, I’ll focus on my policy calls and hit my macro/markets predictions in a later edition.

Like any at-all-impartial observer, I noted in June that taxes would have to go up regardless of who won the election. (“Taxes will in fact need to go up—whatever the main parties say and whoever is in power.”) But I took Labour at its word that raising national insurance—including employer’s NI—would be a manifesto breach. Not what the chancellor thought, as it turned out. If there was any fudging, I thought, it’d be with income tax thresholds. (“Labour has ruled out raising the headline rate of all three [income tax, NI, VAT], as well as of corporation tax (though it may have left some room in its manifesto wording to fiddle with income-tax thresholds).”)

Overall, I expected Labour’s first Budget to cobble together various smaller tax rises, inelegantly. That half-happened, but the main event was a bumper rise to employer’s NI. (“It looks likely that a Labour government would try to muddle through with a bit more borrowing, a sprinkling of tax rises and a little trimming to spending, in the hope that growth will eventually change the fiscal picture.”)

Similarly, on fiscal rules, I foolishly largely took Reeves at her word that there wouldn’t be big changes (“In a pre-election interview Ms Reeves said she would retain the current definition but recently she has sounded more open to changes”). So in August, I suggested that a nice easily-defensible tweak would be to exclude the Bank of England’s QE losses from the debt measure used. Instead, the chancellor opted for a much chunkier set of changes, to the slight dismay of gilt markets.

I did a bit better on the broader picture of where the Budget landed. Few would call Labour’s effort a serious bit of tax reform, which the British economy desperately needs—I pointed that risk out in a leader ahead of the Budget. (“Instead of signalling a once-in-a-generation tax reform, Ms Reeves has trailed a slapdash effort, cobbling together revenue-raisers while trying to wriggle free of self-imposed political constraints. … A budget of this sort would be the hallmark of an unambitious government scrambling to make the figures add up, not a radical one doing whatever was needed to pursue growth.”) A nice bellwether here is stamp duty: it’s politically excruciating to open the debate on property taxes, but stamp duty is clearly a major dampener on growth. Rather than eliminating it, the Budget raised it (for second homes).

The other surprise in the Budget was quite how borrowing-heavy it was. That I did partly point out in September (“Practically, higher headroom means more space for the government to borrow.”), though I didn’t quite anticipate the scale and correspondingly—naively, perhaps—underestimated how poorly the gilt market would react to all that extra debt. (“A shift largely within Britain’s existing fiscal rules, without high inflation or a spat with the OBR, is unlikely to raise hackles.”)

Casting ahead to the OBR’s new forecast that’s coming next month, I did sound the alarm in June on how load-bearing the OBR’s optimistic productivity growth assumptions are. A mild downward revision could throw the government’s fiscal plans into disarray. (According to The Economist’s calculations, if Britain grows by the consensus forecast of 1.5%, rather than the 1.8% expected by the OBR, the annual hole in the public finances would deepen by roughly £30bn ($38.4bn, or 1.1% of GDP).1) And, to drop one extra prediction in, I’d be surprised if the OBR goes for a radical downgrade in March, but that could be a real risk at the next Budget if growth doesn’t pick up by the autumn.

All that adds up to an fine-but-not-phenomenal forecasting record, I’d say. Particularly poor marks for Labour Kreminology.

At last, a growth plan?

About a month ago, during the latest set of gilt market convulsions, I made the tongue-in-cheek point that the bond vigilantes could be Britain’s unwitting saviours—if rising yields shocked the government into a more serious growth policy. That, it now seems, is pretty much what happened.

What have we gotten so far? My best go at a brief summary is: the better of the previously-canned growth ideas from the 2010s (a third runway at Heathrow, a railway connecting Oxford and Cambridge), a few ripped-from-Twitter extras (a new town at Tempsford, early hints at a nuclear push) and a juiced-up AI and datacentre effort.

Quick verdict: all round, a little piecemeal but not a bad few weeks’ effort. The loudest announcements were the new infrastructure megaprojects. It’s worth lingering a little on Heathrow, which I find a particularly excruciating example of how Britain’s gotten this sort of thing wrong in the past. (Anyone already Heathrow-ed out should feel free to skip past the next few paragraphs.)

First: the problem. Britain’s main international hub airport hasn’t gotten bigger in decades, during which time rivals have caught up. I show Schiphol in Amsterdam below as it’s the closest comparator (and partly for the chart pun opportunities), but Dubai or Istanbul would be an even more painful benchmark. Meanwhile, adding a runway has been government policy on-and-off for twenty-plus years2, without a single shovel yet meeting the soil.

I litigate the various arguments for and against expansion in the article, so won’t dwell on that too much here. But briefly: my favourite one-image distillation of the economic arguments in favour of expansion is the map below3. It shows that Heathrow and its surroundings already makes up one of the biggest hubs of economic output in London, aside from the financial centres. When part of the economy has proven it can generate growth and is visibly bottlenecked—this is a theme that recurs in Britain—policymakers would be wise to double down. Bring on the fourth runway!

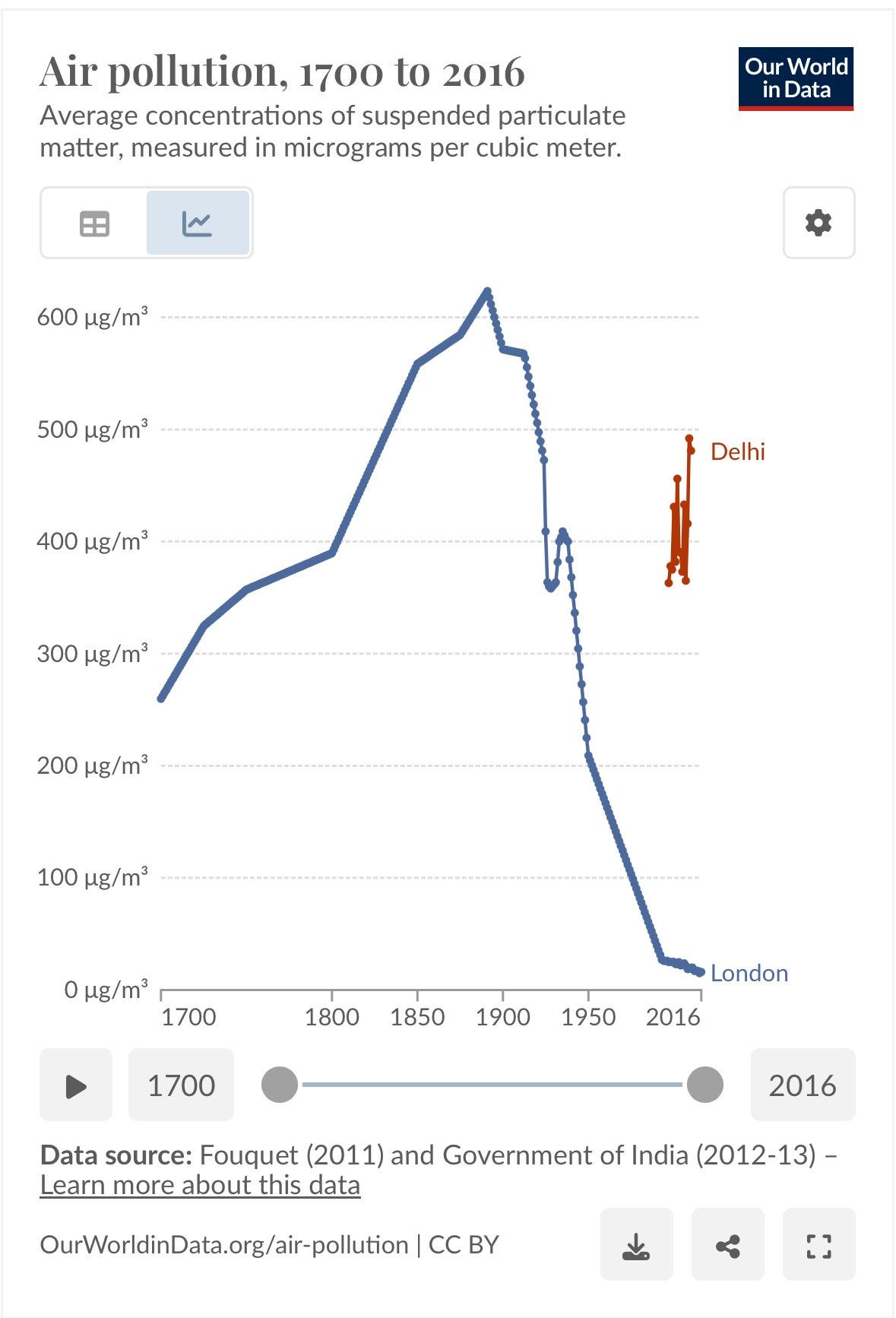

Hopping through the counterarguments, the trickiest are environmental. Lots of the plans for low-carbon aviation rely on some dubious assumptions about advances in sustainable fuels. Expansion strikes me as a highly sensible place for the government to spend its carbon budget, though, and appears to be net-zero-compatible. More provocatively, if the government’s environmental commitments have genuinely made a third runway impossible, that feels like a good litmus test suggesting those commitments need to be rethought. I’ll do some more writing soon, hopefully, on energy, climate, and growth in Britain. (Bad thinking on the topic abounds!) Air pollution is a simplier one. There, a historical perspective is quite illuminating.

What of the rest? The other eye-catching announcement was a revived plan to substantially expand Cambridge, Milton Keynes and Oxford into a rail-connected tech cluster. Not new, but highly sensible. Like Heathrow, the approach seems to be to find a screaming bottleneck (here, in housing and lab space) and tackle it. Worries about over-focusing on the richer areas of the country seem now to have taken a decisive back seat.

Broadly, the announcements on growth so far seem to be:

Highly focused on physical investment and building Britain’s capital stock. (Good!)

Reliant on continued pressure from the top of government. Much softer on self-sustaining reforms that could, for instance, keep a building boom going even with future, less-sympathetic political leadership. (Bad!)

But—some more progress there may be coming in the yet-to-be-detailed planning bill.

Mostly pulling growth levers that won’t make a perceptible difference until after the next election. The urgency to get projects moving swiftly doesn’t, yet, seem colossal. (Politically risky!)

Largely silent on the trading relationship with the EU, Britain’s other big growth millstone. (Bad!)

Still too light on improving Britain’s high-skilled migration offer. That should, in principle, be straightforwardly separable from the government’s goal of getting overall migration numbers down. But in practice the two seem to be getting muddied. (Bad!)

More to say on all of that in due course, and despite all those worries I still net out in a cautiously-optimistic place. It would be disheartening if the government stopped here, but the past month has been much more promising on growth than the previous six.

I also wrote a quick piece last week trying to debunk one of the less-persuasive arguments against the government’s growth plan: that Britain will run out of construction workers.

The history of past building booms shows that, when demand is strong enough, work gets done. Construction in Britain surged during the housing bubble of the 2000s, pulling over half a million workers into the industry. Many left after the financial crash of 2007-09, and have stayed out. After the second world war, Britain’s physical landscape was remade on a vast scale. Further back, in the 17th century nearly the entire City of London was rebuilt within a decade of the Great Fire, and to a much higher standard. Labour markets can quite effectively shuffle workers round when a sector has more capacity and can offer higher wages.

That does require politicians to be flexible. London was rebuilt so quickly in the 1660s and 1670s only because occupational licensing rules were loosened and restrictions relaxed on imports like Scandinavian timber. (“The Norwegians warmed themselves comfortably by the fire of London,” went a saying at the time.) Access to European workers speeded construction a great deal in the 2000s; Irish workers were important in the post-war years.

What else I’m thinking about

First, an open ask to any especially-dedicated readers still reading this far in. I’m compiling data (and anecdote) on the coarsening of day-to-day life in Britain: less-responsive public services, a deteriorating physical environment, an uptick in some petty crime, and so on. Please do shoot over anything worth looking at on those themes, which I hope to write on soon.

And a few more things I’ve been wrestling with:

AI and knowledge work. I spent a chunk of last week playing around with OpenAI’s new Deep Research tool (having decided that $200 was a price worth paying to see if I was soon to be automated). I came away a bit less wildly impressed than some boosters on Twitter, though that may speak to my poor prompting abilities. Still, it’s a phenomenally good aggregator of data and will get a lot better whenever the licensing issues for paywalled news, scientific papers, and copyrighted books get fixed. Lots of compilation work (think tank primers, literature reviews, etc.) will pretty clearly get swiftly commoditised. What I find most immediately interesting is how it shifts the evaluation of knowledge work—lots of shorthands for effort and erudition, like an aposite-but-obscure historical reference, just got a lot cheaper.

How to distinguish between policies that genuinely block growth, and those that mainly just aesthetically offend. One of the more bizarre recent bits of economic news in Britain (well-covered by my colleague Millie Wood) has been a proliferation of equal-pay cases between classes of workers doing manifestly different jobs—the latest involves shop versus warehouse workers at Asda. The substance is a pretty bizarre denial of markets (see below). Certainly, this stuff isn’t doing Britain any good and merits proper reform. But I also wonder if its sheer visible absurdity outweighs its economic impact and can distract finite attention from what matters most. Some—but not all—of Britain’s tax idiosyncrasies (wonky income tax schedule, perverse VAT exceptions) might also fall into this category.

The court left no aisle unscrutinised. Judges weighed up the relative pitfalls of dealing with muttering customers or impatient lorry drivers. Ms Ashton regularly mopped up spills. Mr Opelt had to learn how to operate a hand-held scanner. Both Ms Hutcheson and Mr Ballard used a forklift for some of their work. Rival experts were hired. Precise timings were calculated (Mr Devenney spent 3% of his time tidying). Points for knowledge, communication and “emotional demands” were awarded. Detailed job descriptions submitted for the judges’ consideration spanned over three times the length of the complete works of Shakespeare.

The best things I’ve read recently

The Post-Neoliberal Delusion—Jason Furman

Hard to not enjoy someone thoughtful saying things you agree with. But this was a particularly interesting salvo in the intra-liberal fight over what the Biden era’s turn to economic heterodoxy got wrong.

I was especially glad to see Furman slaying the all-too-prevalent view that supply chain strains during Covid were mainly indicative of impaired supply, rather than overheating demand (for goods): a superficially-appealing but misleading take with astonishing staying power.

Supply chains, meanwhile, were less a source of strain than an underappreciated success. Real consumer spending on durable goods in the United States rose nearly 30 percent above pre-COVID levels in 2021, with no equivalent bump in countries that did not provide continued stimulus checks. Global supply chains were mostly able to accommodate the U.S. increase in spending, in part through large increases in imports. U.S. ports processed 19 percent more cargo by volume in 2021 than they did before COVID, an unusually large uptick that was responsible for the lineup of ships at U.S. ports that many apologists incorrectly attributed to supply chain slowdowns. Ports simply could not keep up with American consumers’ increased appetites for spending. These were not supply dislocations but a huge demand shock stemming in part from the Biden administration’s decision to provide another round of stimulus checks.

On DeepSeek and Export Controls—Dario Amodei

DeepSeek feels a little like old news now, but I thought this—admittedly from a highly partial actor—was one of the more level-headed treatments of how America should process and respond to Chinese AI advances that I’ve seen. I do still struggle to see how any non-frontier AI model maker can justify a decent valuation, though, in a world where open-weights models are only months behind.

All of this is to say that DeepSeek-V3 is not a unique breakthrough or something that fundamentally changes the economics of LLM’s; it’s an expected point on an ongoing cost reduction curve. What’s different this time is that the company that was first to demonstrate the expected cost reductions was Chinese. This has never happened before and is geopolitically significant. However, US companies will soon follow suit — and they won’t do this by copying DeepSeek, but because they too are achieving the usual trend in cost reduction.

And a few of my favourite charts

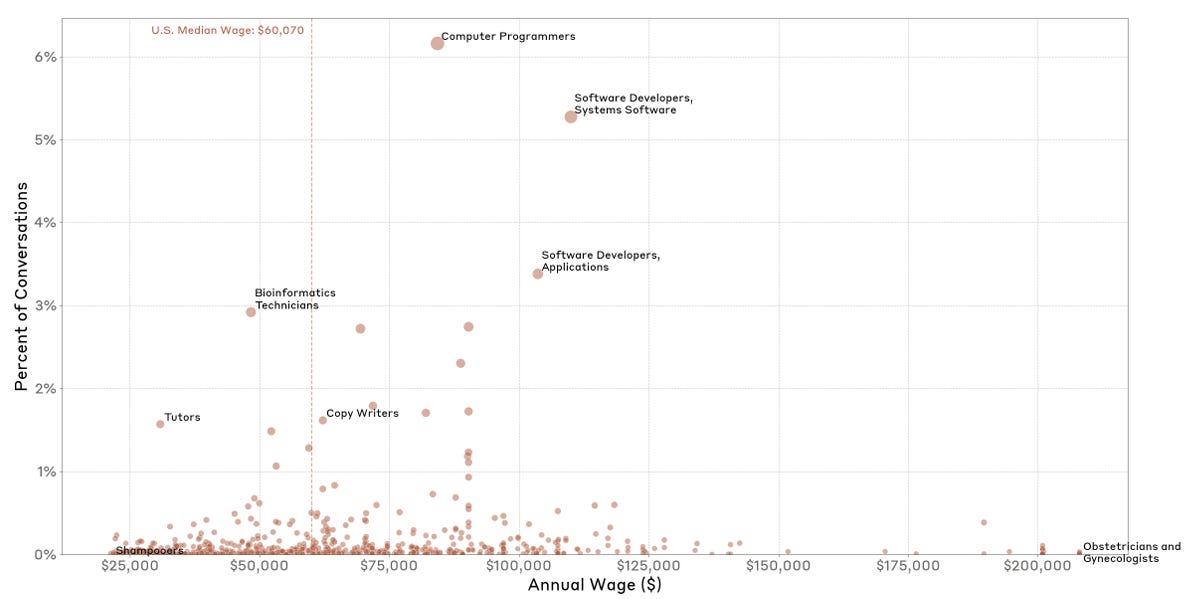

So far, it looks like the only people seriously using LLMs for work are coders, tutors and copywriters. (via Anthropic)

The British government’s price shock to low-wage employment looks even more striking if you fold in the impact of the coming minimum wage rise—shown here in purple. (Via the BoE)

And the crash in British housing starts doesn’t bode vastly well for the government’s plans to sharply ramp up housebuilding over the course of this parliament. (Chart mine)

Finally, it was gratifying to see Happy Days’ The Fonz and/or Arrested Development’s Barry Zuckerkorn taking an appropriately robust stance on Heathrow back in 2013.

Those precise numbers no longer apply, since the fiscal rules have since changed. But the broad principle stands.

Heathrow’s actual passenger capacity has increased over this time period, since planes have gotten bigger. But people better-informed-than-I about trends in aviation tell me that new designs are no longer getting bigger and, on some routes, smaller planes are getting more popular. Without a third runway, passenger capacity could easily fall.

This map shows raw GVA by lower layer super output area (a small census subdivision). A better version of this map would do some sort of explicit population size adjustment—forgive the roughness!

“…if the government’s environmental commitments have genuinely made a third runway impossible, that feels like a good litmus test suggesting those commitments need to be rethought.”

It’s this kind of scientific illiteracy that commits us to the path that risks the collapse of global civilisation.