The day after a Budget always has a strange air to it—bleary-eyed think-tankers present the results of their all-night analysis, with the look of overworked junior investment banking analysts. The gremlins buried in the annexes of the official documents begin to surface. And the initially vague public conversation starts to settle on a narrative.

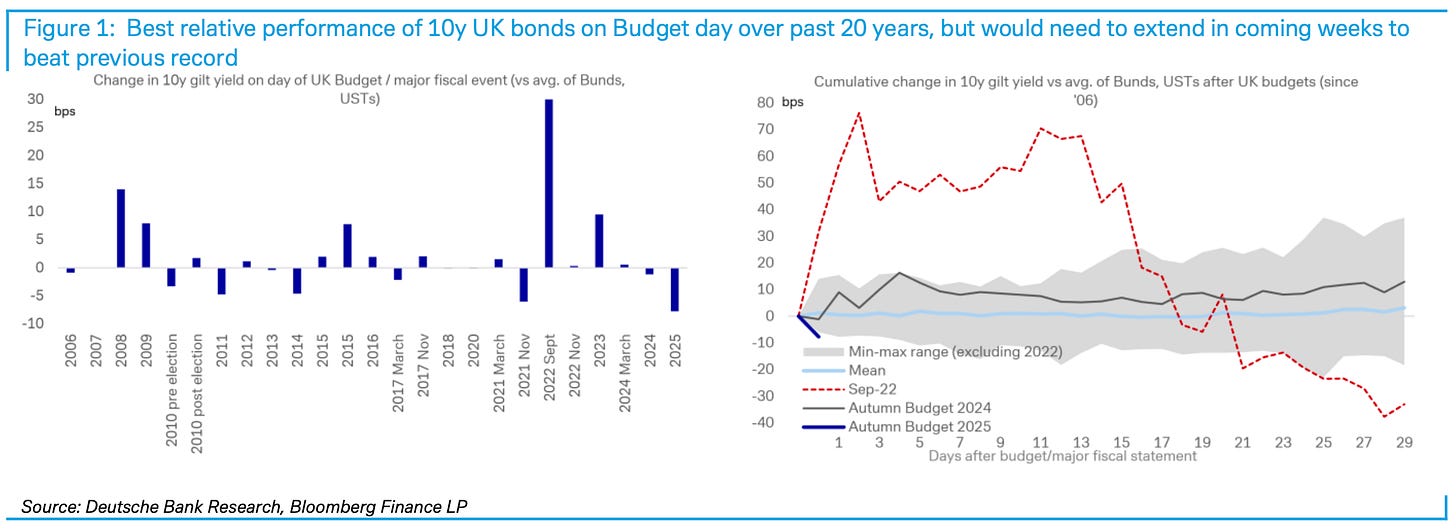

After fiscal events, I tend to keep a running list of what I missed, or under-emphasised, the first time around. Last year it was the brutal bond market reaction, which I nodded to briefly in my initial writeup, but ended up one of the dominant themes of that cycle.

This time around, the economic story was (I think) fairly clear. Not much in my thinking has changed since what I wrote yesterday, linked below. But there’s certainly more to say than I did on how politics interacts with the economics, as well as a few interesting ancilliary points that stuck with me while reading others’ analysis. I figured I’d lay that all out here.

The best way, I’ve decided, to think about this Budget was that there were really two of them. The “first Budget” covers the three years between now and 2028. Its audience was the Labour back-benches and the party faithful. Spending went up, by about £15bn (0.5% of GDP), largely funded with more borrowing. Money for welfare, a bit more capital spending and a few other pots of cash here and there. A Labour government being Labourish.

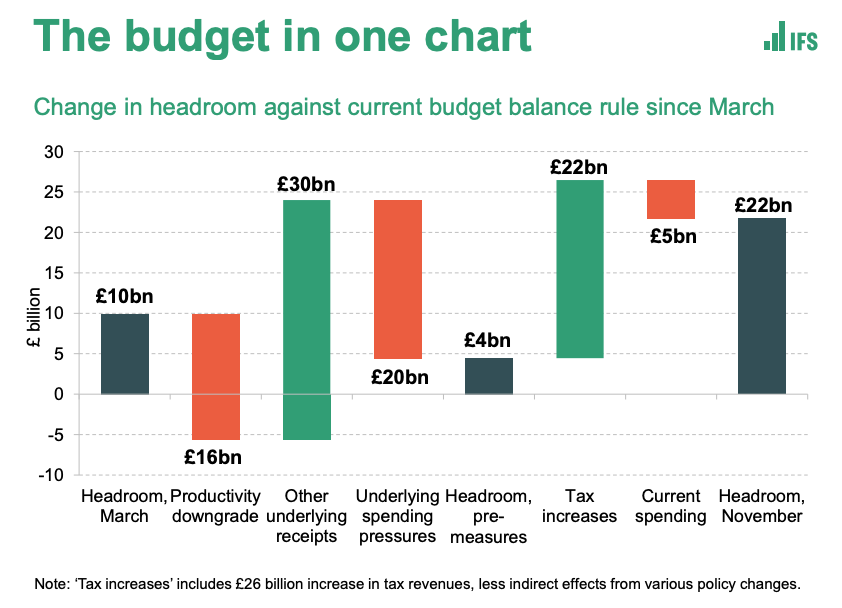

Then there was the “second Budget”, which covers the end of this parliament and into the next. The audience there was the bond market. There, tax rises dominate, mainly via frozen thresholds. Those lift taxes by letting inflation push more people into higher brackets. In total, the extra taxes are worth £22bn (0.6% of GDP) in 2029/30, outweighing higher spending and pushing borrowing down1.

Each side, the chancellor seems to have hoped, would appreciate their slice: Labour gets more social spending, bond vigilantes get a thicker (if back-loaded) fiscal buffer.

But all that was crisis management, keeping the wolves away. And the crisis being managed was political, not economic. After all, the Office for Budget Responsibility’s much-vaunted productivity downgrade turned out to have rather less bite than feared: the nudge down in forecast growth was counteracted (in its effect on tax receipts) by higher projected inflation, real wage growth and employment—meaning more earnings, sitting on average in higher tax brackets.

In simple economic terms, the government could have done nothing and still (narrowly) complied with their fiscal rules2: March had left a £10bn buffer, and yesterday’s underlying forecast changes would have shaved £6bn off, leaving a slim-but-positive £4bn left. You can see that in the left half of this chart from the IFS.

Remarkably, even though the government had much more freedom-of-movement than was signalled, there was virtually no affirmative agenda of any sort. I, of course, would have wanted to see some pro-growth tax reforms. No joy there3. But even last year’s budget had a theory of a sort: that a big boost to state spending, especially capital spending, could mend public services and somehow (the mechanics never entirely convinced) lure in private capital too. The government even persuaded the OBR that all that spending would appreciably boost the supply-side of the economy through capital deepening, albeit more over ten years than five.

This time around, there was really no theory or narrative at all. My colleagues at The Economist framed that gap as “party over country”: delivering another year of inertia that a stagnant country can ill afford. Political survival beat sound economic policy.

And that “second Budget”, the later years of fiscal prudence to keep markets happy, also coincides with the next election. I worry that it would take the self-control of a saint not to—with Farage at the gates of No 10—hand out a few pre-election goodies and delay any restraint by a few more years. The lack of market backlash to that obvious fiction speaks, I think, to rock-bottom expectations. Goldman Sachs, diplomatically, wrote in its post-Budget note that “the backloaded nature of the incremental consolidation … could lead investors to question whether it will ultimately be fully realised”4.

What else?

Having now read through plenty of the overnight analysis on the Budget, I thought I’d also highlight a few more themes that I didn’t fully get to the first time around:

The intergenerational unfairness of the threshold freezes is truly remarkable. Student loan thresholds will be frozen for three years, raising £400m or so a year5. And then the big freezes on personal taxes, of course, mainly hit labour income—earned by people of working age. (Putting a £2,000 cap on salary sacrifice pension contributions whacks that same group too.) Meanwhile, the state pension rate, far from being frozen in cash terms, continues to ratchet up in line with the Triple Lock: the highest of inflation, wages, or 2.5%. This government was voted in with fewer pensioner votes than just about any British government ever, but is still far, far more comfortable raiding the young than the old6.

The markets’ sigh of relief after the Budget was appreciable. By Deutsche Bank’s calculations (see below), it was the biggest differential fall in gilt yields after a Budget in decades. Note, too, the contrast with Labour’s last budget (black line on the right panel below), where there was less focus on the bond market reaction in the lead-up, but a worse reaction later on. My read is that this mainly speaks to the credibility of the OBR, inadvertent early release of its forecast aside. The OBR concluded that the government’s fiscal hole was a bit smaller than widely expected, and that explanation was broadly accepted. Good news for the perceived credibility and competence of at least one important British economic institution.

The limits on salary sacrifice interact unpleasantly with the odd kinks in Britain’s marginal tax schedule (high rates around the withdrawal of child benefit, the personal allowance taper and the withdrawal of subsidised childcare hours). Salary sacrifice at least makes it more painless for earners near those cliff-edges to cram money into their pension to stay on the right side. Credit to Dan Neidle for pointing this out.

Paradoxically, the government’s own sluggishness in delivering its Employment Rights Bill bailed it out. The OBR initially planned to score the growth impacts of the package, which would almost certainly be sharply negative, at this budget, but has judged that there still isn’t enough detail. That could well be a landmine, though, at the next fiscal event.

The decision to levy the new surcharge on expensive homes in “slabs”: from £2,500 per year when a home hits £2m in value, up to £7,500 when it hits £5m, creates lots of unpleasant discontinuities of the sort that tax economists hate. One smart take from Josh Bailey of the EIU is that this may have been done to reduce the number of valuation challenges. Perhaps deluded optimism, but I also hope that getting any sort of regular tax on the current-ish value of a home is one step towards normalising the stamp-duty-for-property-tax swap that Britain obviously needs. (See proposals on that from Tim Leunig and from the Centre for British Progress.)

Peculiarly, the OBR will still produce two sets of economic forecasts per year, but only assess the government against its fiscal rules in one of them. That will lead to the slightly strange outcome of every wonk doing their own DIY arithmetic on the OBR spreadsheets to work out for themselves how much headroom the government has, given pretty much all the necessary underlying information would be there. But perhaps that dials down the political heat if the government is close to the line, and certainly Britain needs less fiscal fine-tuning, not more.

The government was disappointingly non-commital in its response to the Fingleton Review, an excellent set of proposed reforms to nuclear power. One to watch, where a bit of boldness could go a long way.

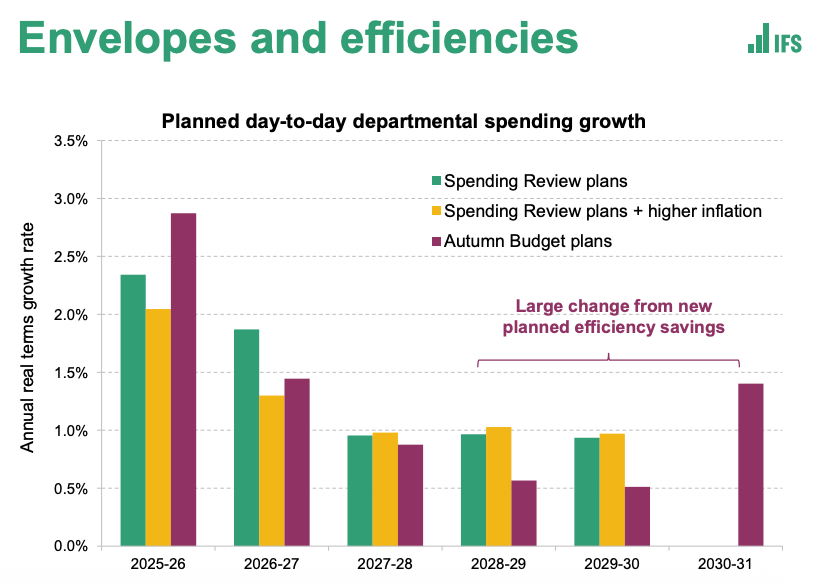

Day-to-day spending growth towards the end of parliament has been pared back from about 1% per year to 0.5% per year. The government has promised “efficiency savings” will drive this, but re-opening 2028/9 spending after it was notionally finalised in the spending review over the summer isn’t a great look. More from the IFS’ Bee Boileau.

The government will start absorbing special-needs education spending pressures later on this parliament, rather than continuing to dump them on local councils. That is a good thing, and should align incentives well to reform the current unworkable system. But the prospect of a nearly 5% decline to per-pupil spending in mainstream schools when that happens, as the OBR forecasts, is pretty hair-raising.

The two-child limit is a parable of how to get unpopular things done in this government: a concerted campaign of pressure from within the Labour party. Stephen Bush notes in the FT that:

“But compared with the two-child limit, very few of those unpopular policies have enough power brokers and organisers within the Labour party to campaign for and drag the government into taking action. There is no equivalently powerful Labour caucus saying “for goodness’ sake, stop putting more cost pressures on to businesses if you want growth and you want action on the cost of living”.

There is no equivalently powerful Labour caucus for NHS reform. And there is no equivalently powerful caucus for putting the public finances in a sustainable position. Given that, it seems unlikely that this government will be dragged towards meeting even its own objectives, let alone anyone else’s.”

And, to wrap up, I would have loved to sit in on a Budget lesson7. Ailbhe Rea in the New Statesman reports that in the lead-up to yesterday, “there were “Budget lessons”, aiming to teach MPs how debt interest works and why borrowing more would result in more money going to US hedge funds”. I would add that, if those hedge funds do their job well, most of that money should eventually go to US public sector pension funds and the like. But perhaps the California teachers aren’t quite as convenient a bogeyman.

That’s, at this point, I suspect truly more than enough Budget parsing for all but my most fiscally-obsessed readers. I do plan to return to a slightly more regular posting cadence on here (with a mixture of US and Britain-focused writing) over the next month or two, though. So please do subscribe for that, if you haven’t already.

Forgive my recycling of a chart from last time, but I think it’s the cleanest way to show how different the two Budgets are.

The pain of leaving a narrow fiscal margin will also be less going forward, since the OBR is now only formally scoring the government against its fiscal rules once per year, at a major fiscal events when governments would be expecting to make policy changes anyway.

I do think the EV tax changes are a good thing (though could have been better targeted at congestion), and hopefully open the door to proper reform of road taxes down the line, as Dan Tomlinson MP has pointed out. But the good news on reform pretty much stops there.

The best counterpoint I’ve heard from the Labour side is that threshold freezes are much lower salience than spending cuts (the bulk of the consolidation that was put off under the Tories), so will be easier to stick to. Of course, one could stick to them and then undo the consolidation by adding extra spending as well.

Plus, thanks to the odd accounting norms of Labour’s debt rule, “reducing” capital spending next year by increasing the discounted value of the student loan book as a whole.

One partial exception is the new, higher rate of income tax specifically for property income, which I would guess is pretty skewed towards older people. Plus the high-value property taxes.

Next time around if No 11 wants to invite me to stop by one, I promise to be well-behaved!