12 Thoughts on the Spending Review

"Don't tell me what you think, show me what's in your portfolio."

Naturally, I am contractually obliged1 to say that the best place to go to understand Wednesday’s spending review—where the British government decided what to fund through early 2029—is what I and colleagues wrote for The Economist in the hours afterwards.

But with a few days’ distance, and the benefit of also reading others’ analysis, I thought it’d be worthwhile to pull together something a bit more detailed (and wonkier) for here.

The best way to think about the spending review, I think, is through the finance-world line “don't tell me what you think, show me what’s in your portfolio.”2 The government has had almost a year to tell voters what it cares about. But doling out cash forces choices, and makes clear where priorities really lie.

So, here’s that piece in—God forbid—listicle form.

Let’s begin with what to ignore. I’d pay pretty close to zero attention to Rachel Reeves’s actual speech.

Here’s what I wrote about it at the time.

“For almost an hour on June 11th the House of Commons felt like a bingo hall, or perhaps an auction house. Rachel Reeves reeled off a dizzying list of wildly varying numbers and time horizons, covering programme after programme funded in Britain’s spending review. … All that razzle-dazzle served a purpose: to pull eyes away from the harsh trade-offs the government had actually made in allocating money across departments.”

More than most British fiscal events, I also thought this was one where much of the press coverage largely missed the point.

Lots of outlets (not that I’d ever name names) seemed to get a little taken in by the government’s strategy of announcing exciting-sounding projects, promising a generational programme of investment and so on—without realising that money was tight and the fact that one railway or power plant was funded said little about the more significant question of what happened to overall transport or energy spending.

There is one exception. Rhetorically, that was the most protectionist speech that I’ve seen Reeves give since becoming Chancellor, by some margin.

Take the passage below.

“I have long spoken about what I call ‘securonomics’:

The basic insight that, in an age of insecurity, government must step up…

…to provide security for working people…

…and resilience for our national economy.

Put simply: where things are made, and who makes them, matters.” (emphasis mine)

I’m hardly an expert Labour-whisperer, so won’t dwell long on the internal politics of that shift, but clearly the Reform threat and the feeling that momentum is with Labour’s “soft left” seem to be having an impact.

From a policy point of view, I never found Reeves’s cod-Bidenomics “securonomics”—which was all over Labour’s campaign materials in 2023 and early 2024, before mostly getting canned3 ahead of the election—to be vastly convincing. Whatever one thinks of a government-funded push to reshore production in America4, Britain’s smaller scale and more limited fiscal firepower would always make that especially tough here.

The actual policy shifts accompanying that change in rhetoric so far don’t look vast, but a few details look troubling. Pushing Heathrow to only use British-made steel is exactly the sort of everything-bagel nonsense that Britain needs to be moving away from. Nor should governments be putting price controls on school uniforms, as Reeves also proposed.

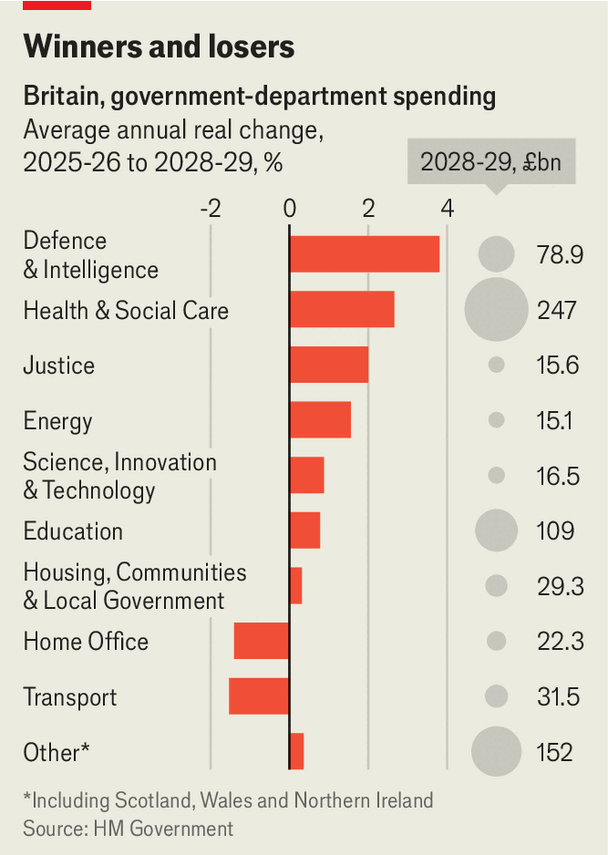

Money-wise, there were two clear winners: defence and health.

I framed this earlier as Britain getting closer to becoming “a hospital with an army”. Emily Fry from the Resolution Foundation helpfully refined that to “doctors and nurses with a lot of jets and tanks”, since the boost to health came in day-to-day spending and the boost to defence came in capital spending.

You can see that pretty clearly in the chart below, which I made on the day. This pulls together both day-to-day and investment spending. Purely in percentage terms, health and defence already visibly come out best. That is even more pronounced in cash terms given how big the two are, especially health, which is getting a budget of nearly £250bn by the end of the spending review period.

The government has doubled down on the bet that fixing the NHS is its route to re-election.

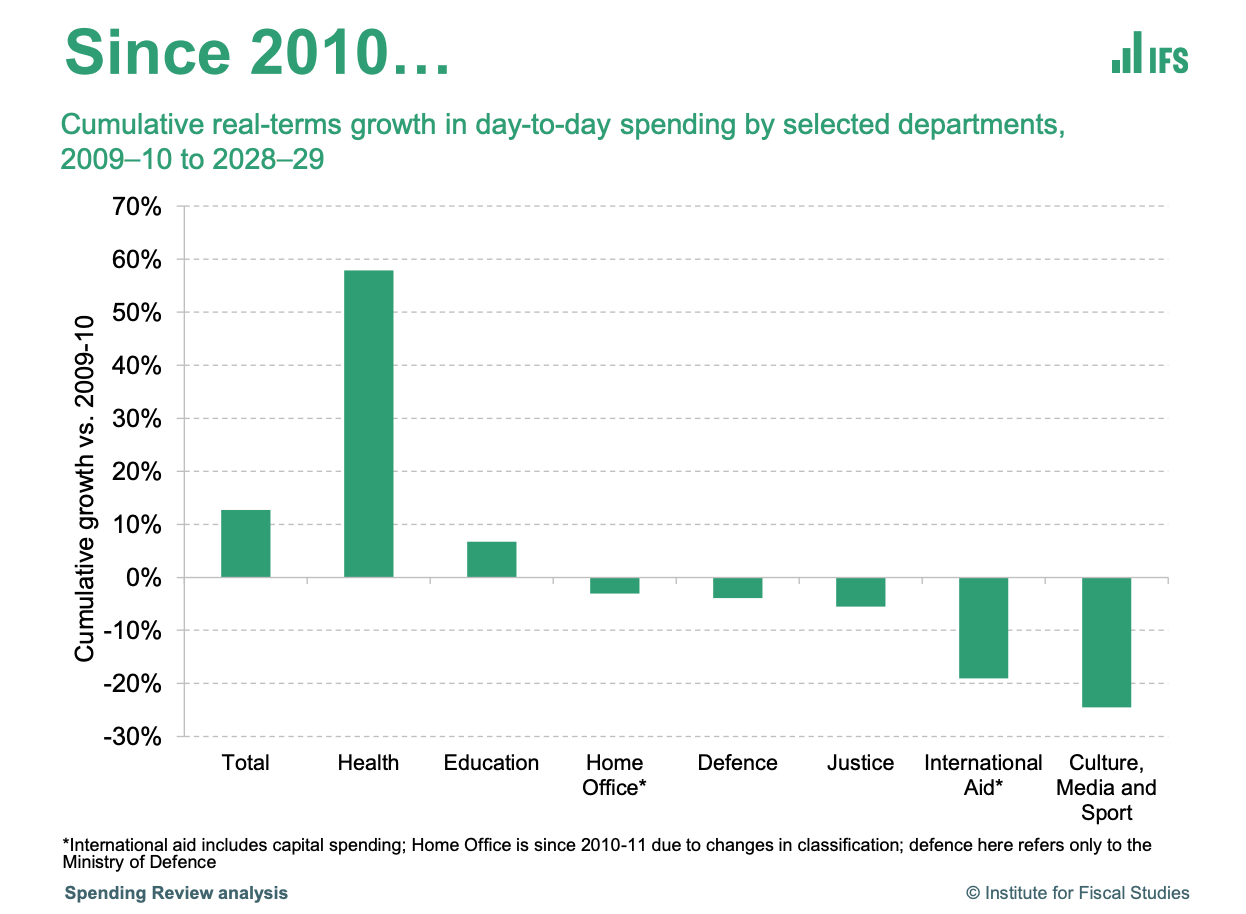

That actually marks a striking continuity with previous Tory governments—which were generally much happier squeezing the rest of the public sector than the NHS.

The conversations around whether Labour was delivering “austerity” were always a distraction; calling an October budget that raised planned annual spending by 2% of GDP “austerity” is clearly foolish. But the government’s fund-the-NHS-at-all-costs strategy has more in common with its predecessors than either side would probably be willing to admit.

The chart below from Bee Boileau at the IFS lays that out well. Those cuts to departments outside the NHS would also look even bigger in per-person terms, taking into account population growth5.

Regular readers of this Substack, insofar as those exist, will know that I’m a bit uncertain about that strategy, and tend to think there may be cheaper and easier wins by putting cash into things like basic local government services, rather than putting every electoral egg in the NHS basket.

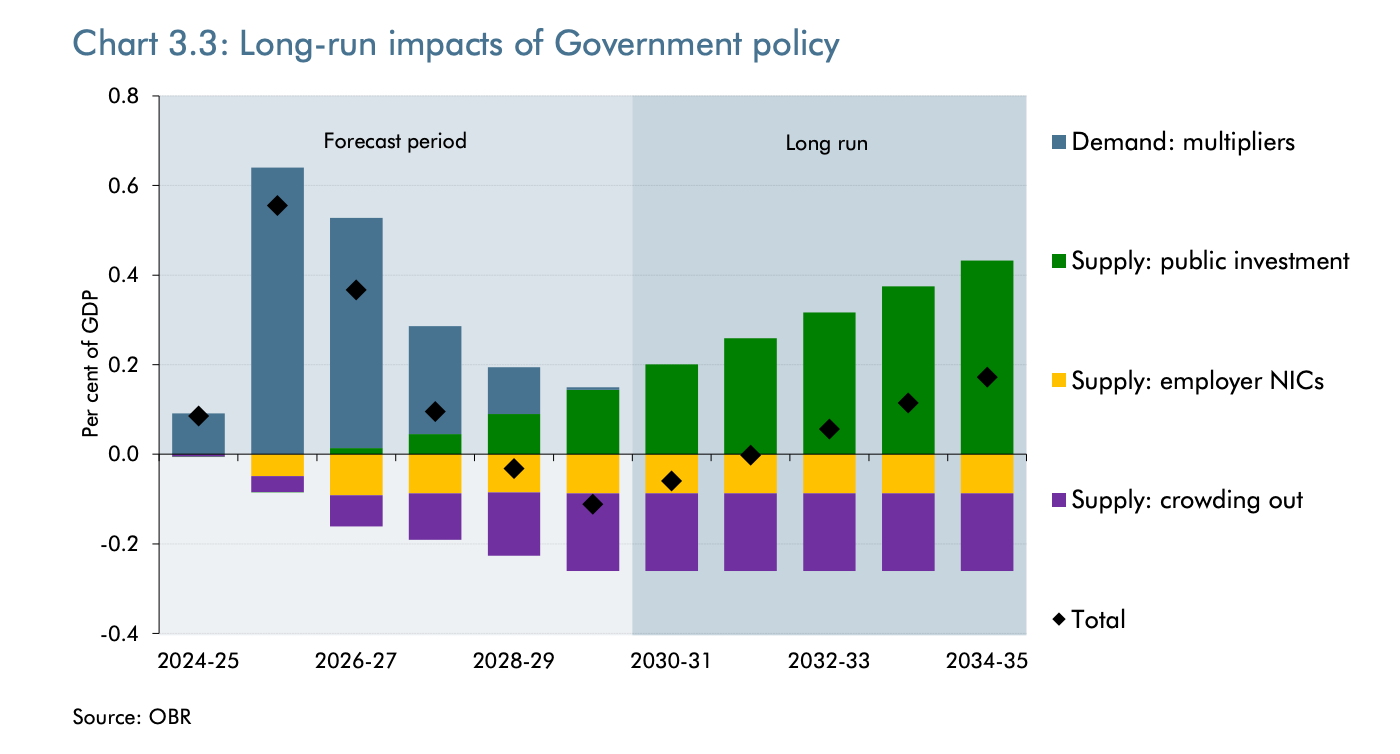

“Invest-to-grow” has become mostly a mirage.

Coming out of October’s budget, the narrative from the government was that it was dialling up investment to grow the economy. The OBR was persuaded to produce charts like the one below, going beyond its usual five-year forecast window to show how an uplift in investment would have big supply-side implications further out.

Then, Donald Trump was elected and focus shifted to defence spending. There’s a long literature in economics on what spillovers defence spending has to the rest of the economy, which I’ll largely elide here. But suffice it to say that growing the economy is clearly not the point of defence spending (nor should it be), and that tanks and munitions clearly boost Britain’s productive capacity by less than roads, railways and power stations.

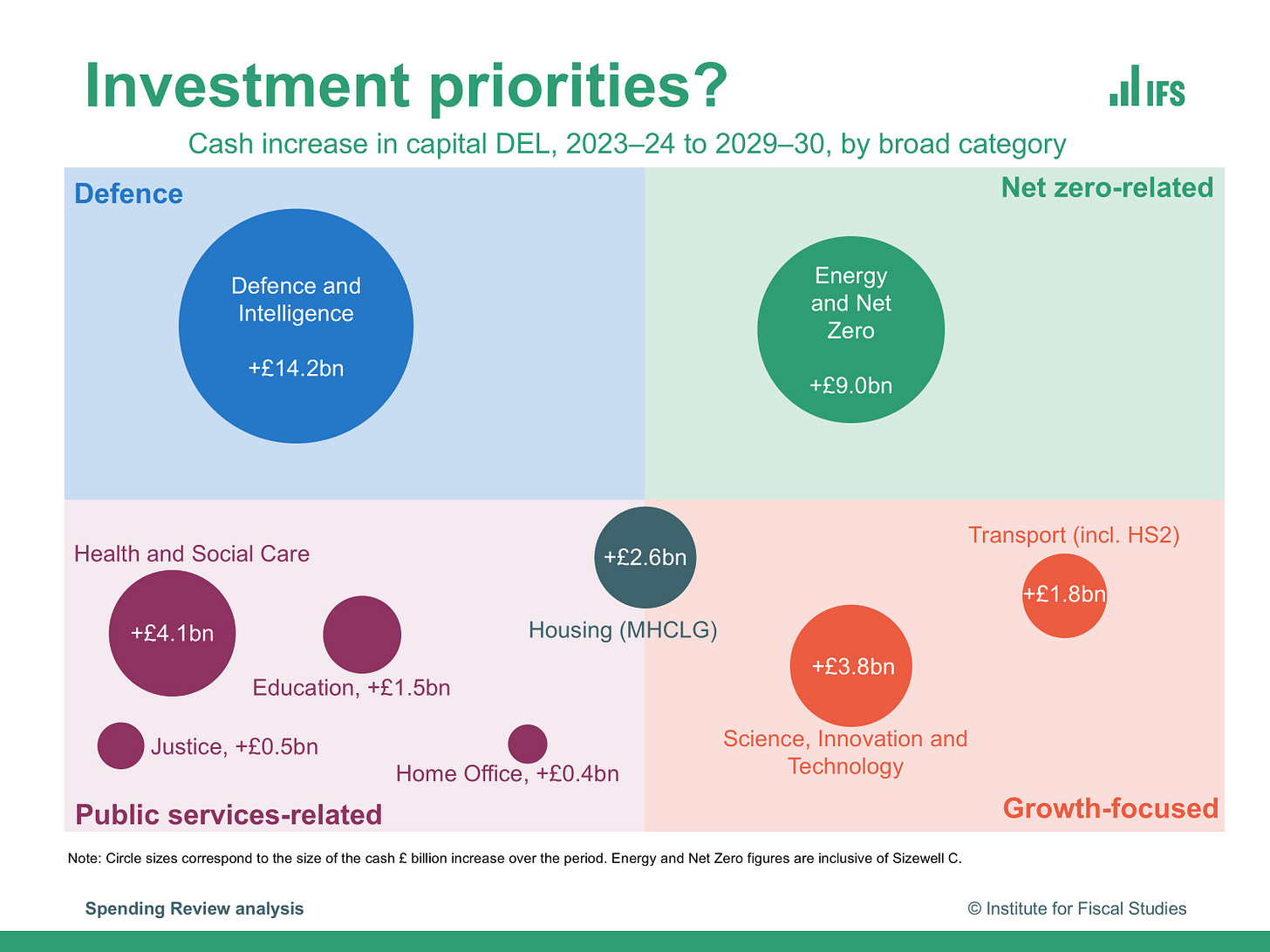

Ben Zaranko at the IFS did a pretty helpful rough-and-ready breakdown of where investment went, which you can see below. Note how small the circles on the bottom right, for explicitly growth-focused areas, are. And he is showing the numbers in cash terms—transport would be negative if these were adjusted for inflation.

In fact, if you cut out “financial transactions” (loans etc., more on this later), the Resolution Foundation calculates that non-defence investment will actually see real-terms cuts between 2025-26 and 2029-30.

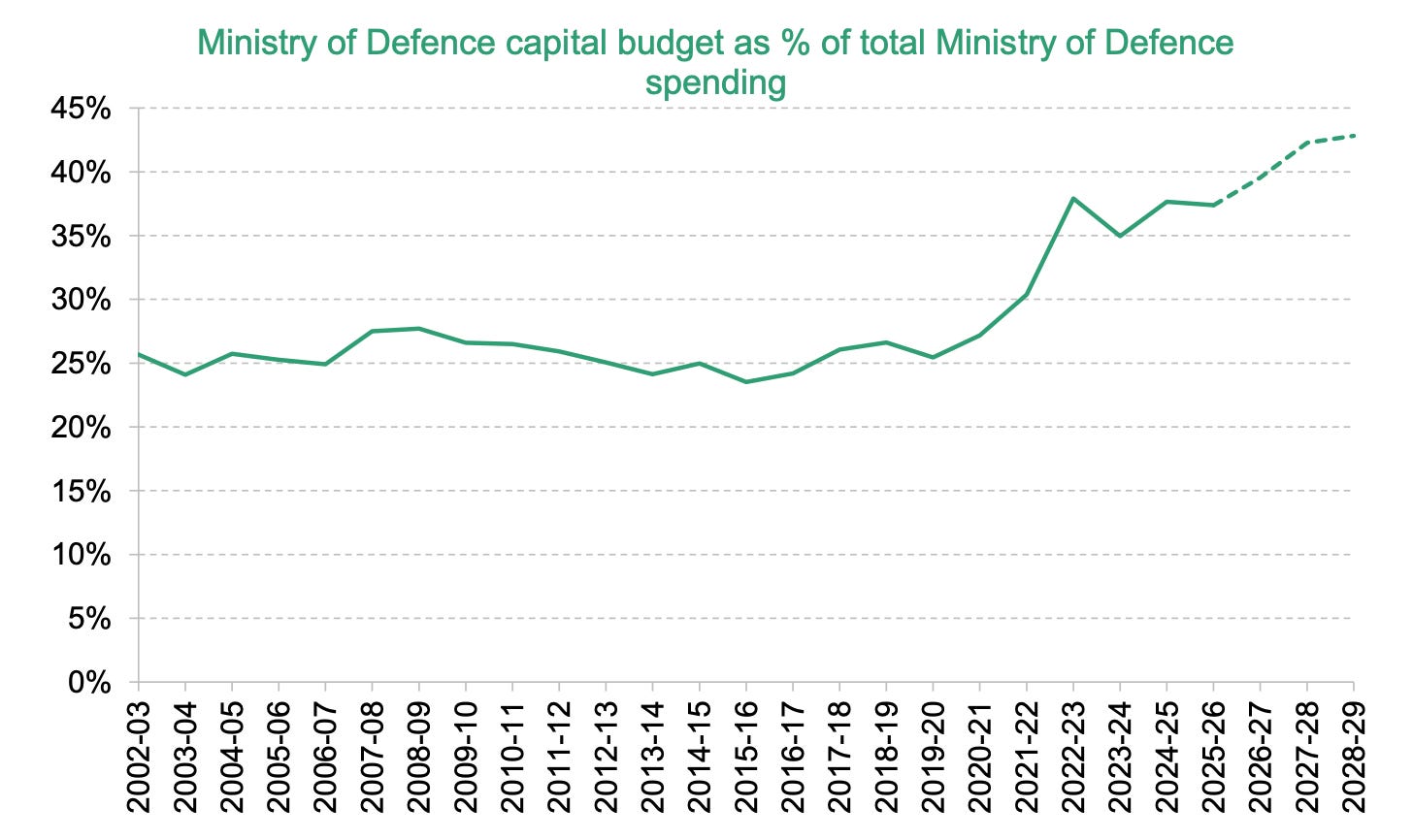

Another peculiar implication of the government’s decision to use investment as the vehicle to raise defence spending is that the composition of defence spending has now changed quite a bit, from 25:75 investment versus day-to-day to more like 40:60, as the chart below shows (also from Bee at the IFS). A rather odd case where the edge-case quirks of Britain’s fiscal rules may literally reshape how its military works.

The Sizewell C nuclear plant is a noble exception to that lack of growth-y investment.

Sizewell makes up a decent chunk of the “energy and net zero” bubble above, and should provide 7% of Britain’s electricity once it opens in the early 2030s.

The fact that the government has had to take a majority stake in the project is a little worrying, suggesting that the private sector isn’t vastly keen on financing large-scale nuclear power in Britain. Still, what matters most is that the project is moving along. I’ll save further thoughts on nuclear in Britain for a later post.

The government’s thinking on the housing crisis seems to have moved backward.

Reassuringly, this government’s diagnosis of the problems in the housing market has usually sounded basically right—that housing supply is too low, largely due to over-onerous planning regulations. There’s still lots to quibble with on their actual policies, which underrate the importance of building in city centres, are too top-down and target-driven, and don’t go far enough on moving away from a site-by-site discretionary process.

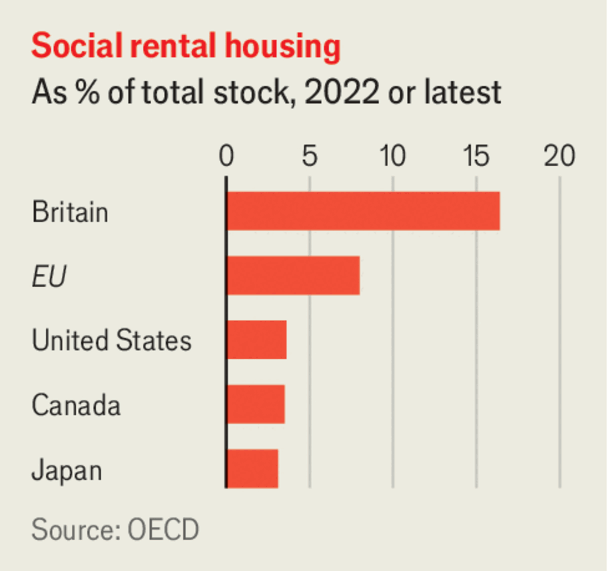

But the huge focus on a £39bn fund for social and affordable housing struck me as a bit of a return to the largely-debunked idea that housing is expensive because not enough of it is “affordable”, rather than that it’s in too short supply. Housing is also a place where—with appropriate deregulation—the private sector can quite easily take the lead. So at a time when government cash is so tight, that struck me as a slightly strange place to allocate scarce public funds6. Better, I’d say, to focus on something like big infrastructure projects where government involvement is inevitable.

Besides, as my colleague Henry Curr points out in a great leader article, Britain already has more social housing than most peers.

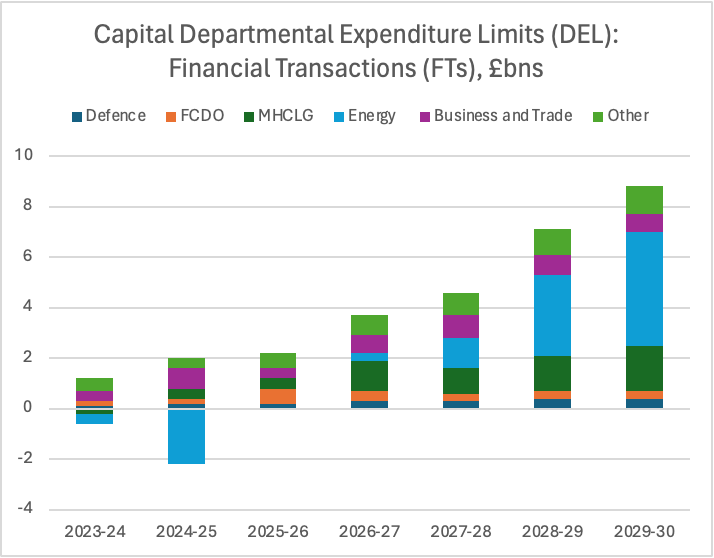

Watch the government’s use of “financial transactions” to squeeze out more borrowing.

One feature of Public Sector Net Financial Liabilities, the debt-adjacent concept that one of Reeves’s fiscal rules now targets7, is that transmuting projects into financial instruments like loans or equity stakes (versus simply paying for them) means the Treasury can net off their value and not add to total “debt”.

Thus, for the narrow purposes of fiscal rules, that spending is near-free. (Not quite, since higher interest costs from more borrowing do also flow into the fiscal maths. And the bond market, which is what actually matters, cares far more about the volume of borrowing than its categorisation.)

For now, the amounts involved aren’t huge, but the government is planning to ramp them up, especially for energy and housing. Here’s a quick-and-dirty chart of mine showing the breakdown. Something to watch.

The spending review figures rely on continued 5% increases in council tax.

The parlous state of local government finances in Britain is well-reported (and is something of a fixation of mine). So most councils are already raising council tax by 5%, the maximum they can without calling a referendum. The figures in the spending review presume that continues.

At some point, I think there’s a good chance that the ever-upwards ratcheting of council tax starts becoming a real political problem, particularly if the local government services most people use don’t improve.

London lost out.

One of the more inexplicable features of Britain’s fiscal system is the inability of cities to raise their own revenue, either through local taxes or borrowing. That forces them to show up with a begging-bowl to the Treasury for funding. This time, the loser was London, which got neither of its two big requests, as my colleague Joel Budd writes.

“When the chancellor’s spending review mentioned London, it was often in the context of promises to close government offices and move civil servants out. The capital had two big requests, for money to extend the Docklands Light Railway and the Bakerloo Underground line. Both got short shrift. The contrast with Birmingham and Greater Manchester, which will be able to extend their tram networks, is plain.”

What noisy macro variables give, they can also take away.

I always find myself slightly offended by how shamelessly governments (of all stripes) are in claiming credit for short-term macro changes they had little-to-nothing to do with. So Reeves’s speech had the line:

“And the latest figures showed we are the fastest growing economy in the G7”

The chancellor neglected to add that this was only for the first quarter of 2025. On any longer time-frame, even just looking back a year, Britain’s growth is far shabbier. Quarter-to-quarter GDP movements aren’t quite random, but certainly aren’t stable enough that a government should be putting all that much stock in them.

So there was a certain irony when on Thursday, the day after the spending review, we got another month of GDP figures which recorded a -0.3% month-to-month fall, wiping out Britain’s lead.

The next budget is shaping up to be a real mess.

And finally, there was a slight air of unreality about a spending review that doled out money based on a set of forecasts which were put together before ‘Liberation Day’, when Donald Trump’s tariff antics started to seriously look like a threat to world (and British) growth.

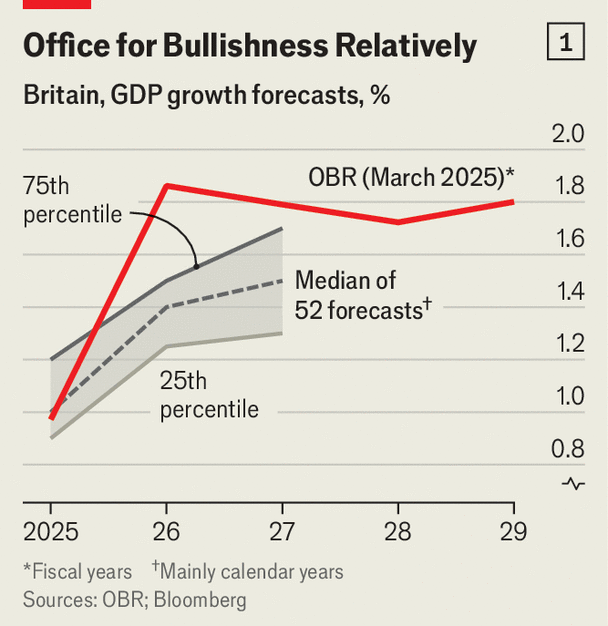

The OBR, as I’ve written before, may well (and should, I think) revise down its unrealistically-high growth estimates for Britain. But doing so could easily knock out tens of billions in fiscal headroom. The chart below shows quite how much of an outlier the OBR now is.

That conversation will pick up over the summer. But for now just bear in mind that the messiest, and most consequential, fiscal event of the year is probably still to come.

I am not. But I do think our coverage was good!

Originally a Taleb-ism, if memory serves.

My colleague Matthew Holehouse wrote a great piece on this in November. But perhaps (at least in terms of rhetoric, the substance of the ‘securonomics’ agenda remains thin) we pronounced the death rites too early.

And I have plenty of questions there too—a topic for another piece. But Jason Furman in “The Post-Neoliberal Delusion” lands very close to where I would overall.

Note that the IFS chart is just day-to-day. Defence comes out much better once investment is folded in.

Countervailingly, lots of the headlines exaggerate the scale of that programme. The £39bn is over ten years, and the actual uplift to MHCLG capital spending is far lower than that. Much of the money comes simply from ringfencing and rebadging funds that MHCLG would probably have been allocated anyway, on the basis of prior spending patterns.

The other main rule, which binds harder, is that day-to-day spending should be paid for by taxation not borrowing.

Great piece!

I think the only area I disagree slightly is on social housing - where the exorbitant funds we're currently paying on housing benefit could make this a better investment than it might otherwise appear. Though I'd prefer a greater focus on councils directly building new social housing, rather than (as I suspect will happen) most of the funds just being used to buy up vacant properties.

Social housing isn’t the answer. We are not a totalitarian country like Singapore which can railroad the nation into 75% social housing.

I do not trust councils to build the right types of houses or estimate demand properly, or build them at low cost in a timely manner.

And who’s to say the NIMBYs objections won’t be there for these houses? I can see “will attract the wrong kind of people” arguments from a mile.

Loosen supply side regulations and the market will sort itself out.