Here’s one of my most crankish investing views (not financial advice!): for most Brits, the optimal allocation in their savings to UK assets is 0%, in other words to hold no domestic stocks or bonds at all1.

That’s not because of any particularly dire prognosis about Britain. But diversifying holdings across countries2 is one of the few truly costless ways to lower risk and raise expected returns in a portfolio. Plus, if you take a more holistic view of people’s “portfolio”—to include their home3, the present value of their future earnings (net of future spending), potential eligibility for a state pension and so on—almost everyone is inescapably vastly over-allocated to the place they live. No point adding to that exposure with investments too.

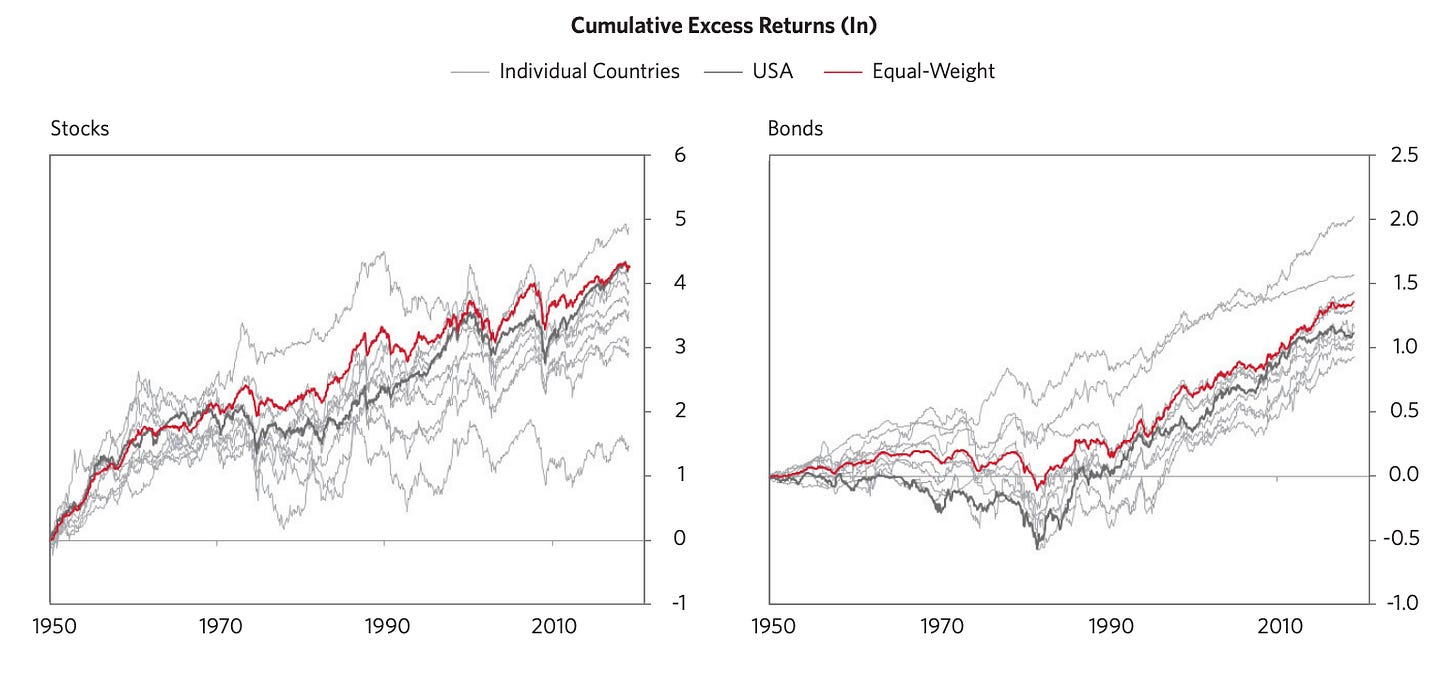

The chart below, from my former employer, illustrates the stakes. A globally diversified return stream (the red line) has for decades been a higher-returning strategy with less volatility than choosing one specific country (the grey lines).

You could even take the logic further. Given the scale of their personal exposure to Britain through wages and so on, should Brits in fact have a negative allocation to UK assets—in other words go short the FTSE to raise cash to build an even bigger position in the S&P 500, Eurostoxx and Hang Seng? Perhaps there’s a niche fintech product in that…

All this is mostly a provocation, but I do find the logic fairly compelling. And in reality, most investors, both in Britain and elsewhere, do the opposite. They exhibit substantial “home bias”, over-allocating to their own market relative to its size.

In fact, Britain over the past decade is a perfect case study for why home bias is so damaging. Weak growth has pulled down wages and also hit British businesses, so UK equities have underperformed. Even British-listed international businesses (like many on the FTSE 100) have lost out, since investors have grown more cautious about sterling-denominated assets after Brexit and the Liz Truss episode.

No-one living and working in Britain was able to avoid the former hit (slow growth hurting wages), but people could choose whether their investments reinforced that shock (by holding lots of British assets, which underperformed for the same reasons) or counterbalanced it (by holding global assets, which weren’t affected4).

Instead, the position of successive British governments, including Labour today, is that British savers need yet more home bias. That has long struck me as profoundly misguided. Last Thursday, the Pensions Investment Review put out its final report, reaffirming that position and arming the government with tools to make pension funds comply.

I’ll walk through those briefly, but want to spend the bulk of this post having a go at taking apart the arguments in favour of actively pushing more Brits to invest domestically.

Start with Thursday’s pensions report. Much of what’s in there is highly sensible and long overdue, especially on consolidating smaller schemes to realise the benefits of scale. I do want to re-emphasise that none of what I write should be read as defending the chaotic and underperforming status quo in the British pension world.

But on the home bias question, the proposals are rather less promising5.

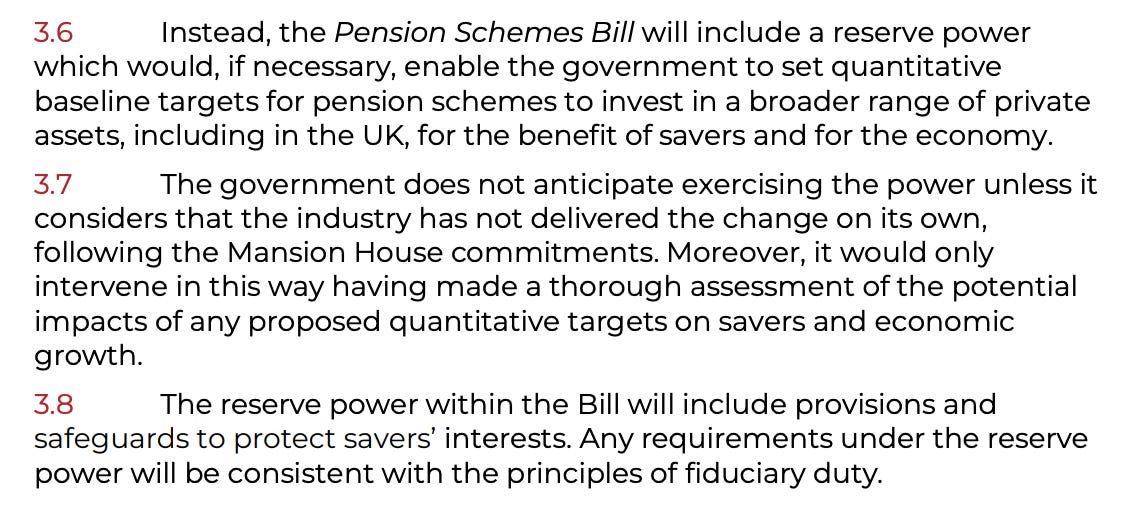

The government has decided not to go ahead with explicit mandation—i.e. forcing schemes to hold a certain share of British assets. (Good!)

But: that is only because of promises (the Mansion House commitments) that some of the largest pension schemes have made, and the government is creating a “reserve power” to force mandation later on. (Less good!)

That, to be clear, smells a lot like backdoor mandation: the government waves about the threat of forcing pension funds to hold more British assets, before generously deciding not to fully exercise it once funds get the message and “voluntarily” make sure to allocate the money within Britain anyway.

The refusal to acknowledge that this choice involves tradeoffs also particularly rankled me. How, exactly, can forcing fiduciaries to buy assets they wouldn’t otherwise have chosen be “consistent with the principles of fiduciary duty”?

Better to simply embrace the tradeoff and pick a side. My bid would be to make the single guiding question for pension policy: what needs to be done to make sure British savers are getting the highest returns in the world?

Clearly, that’s not where the government is. Nor is that attitude something specific to Labour. The Conservatives’ “Brit ISA”, a now-ditched tax break to persuade ordinary people to buy more British shares, stemmed from similar thinking. It’s worth understanding that cross-party enthusiasm. As I see it, there are three main planks:

A lack of domestic capital hurts growth, since some good projects and companies don’t get funded.

Even when foreign capital does come in, having an overseas investor base is a problem. Valuations suffer and promising companies may eventually follow their investors and move overseas.

Those effects are substantial enough to outweigh the benefit of chasing higher returns to make British savers richer.

None of the three holds up, in my view. Let’s walk through them.

Premise 1: Capital is a bottleneck to growth in Britain

To believe that we need to force more British savers to invest at home, we’d need to think that there are high-return investments—infrastructure projects, expansions by companies, start-up funding, and so on—that are being held back by an inability to get investors interested.

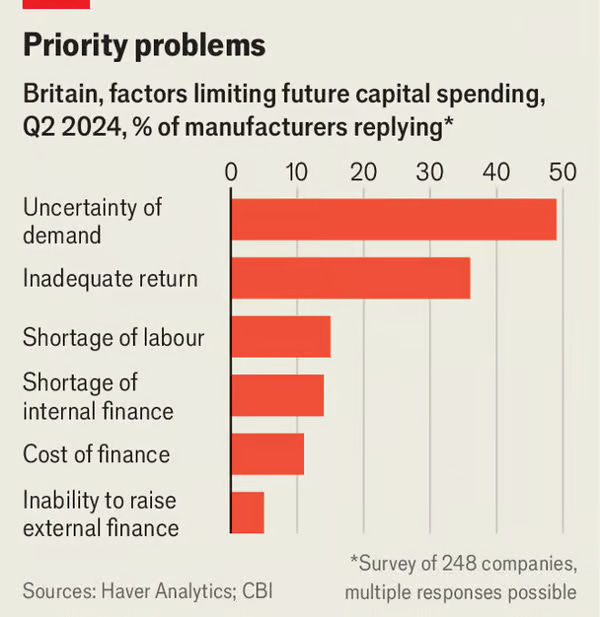

One way to sense-check that view is to ask companies. Thankfully, Britain has long-running surveys that do exactly that. I took a look at one, the CBI’s Industrial Trends Survey, last year when writing about the National Wealth Fund (another initiative premised on financing being a big bottleneck to British growth). The CBI asks a panel of manufacturers why they aren’t investing more in capital, like new machines and buildings.

Almost always, as you can see in the chart below, the overwhelming issue is a lack of sufficiently appealing opportunities (“uncertainty of demand”, “inadequate return”). Cost-of-finance worries (“shortage of internal finance”, “cost of finance”, “inability to raise external finance”) were among the least popular responses.

Intuitively, that makes sense. Whatever one’s quibbles about Britain’s financial system, it remains one of the deepest and most liquid in the world. You don’t have to be an efficient-markets purist to find it difficult to believe that vast, sophisticated international investors are foolishly overlooking countless exciting opportunities in Britain, an English-speaking country with robust rule of law.

Back in April, BlackRock’s Larry Fink told The Times that lots of British assets looked cheap, now that the political situation had stabilised, and that he was putting money in. Make Britain a genuinely appealing economy and both domestic and international investors will be happy to pony up cash.

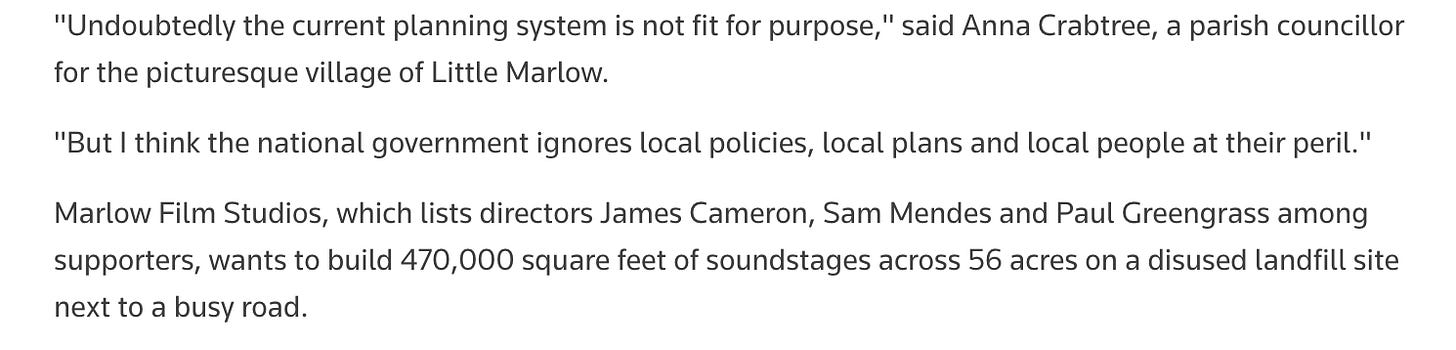

Meanwhile, Britain is full of straightforwardly damaging real-economy bottlenecks to growth, like the planning system. Making progress there would do far more good.

Perhaps, for instance, investors would be keener to put money into Britain if it didn’t take over four years and the personal intervention of the Deputy Prime Minister to get (still-outstanding) approval to build some film studios on the site of a former landfill in Buckinghamshire.

Premise 2: Having an overseas investor base is a problem

A subtler version of the argument accepts that projects and companies can get investment, but frets that getting money from overseas bodies like Canadian and Australian pension funds (for whom, critically, exposure to Britain is genuinely diversifying) is a problem.

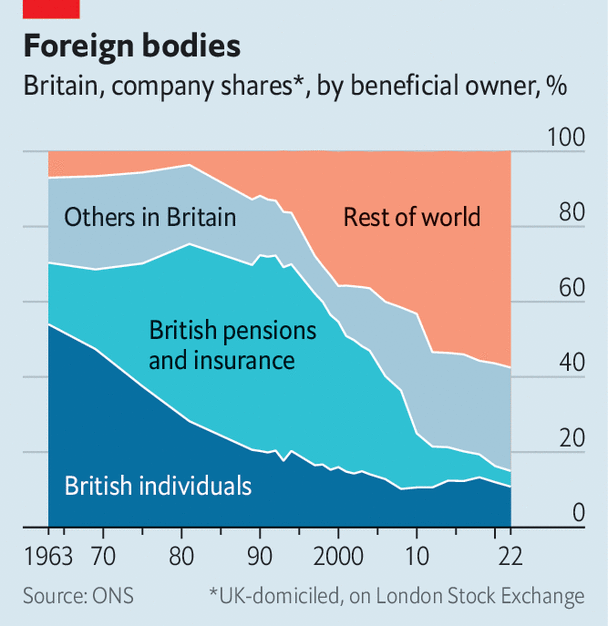

Certainly, there has been a big shift in who owns British equities, as the chart below shows.

You generally come across three views on why that’s a problem. (The first two are, in my view, more serious than the third).

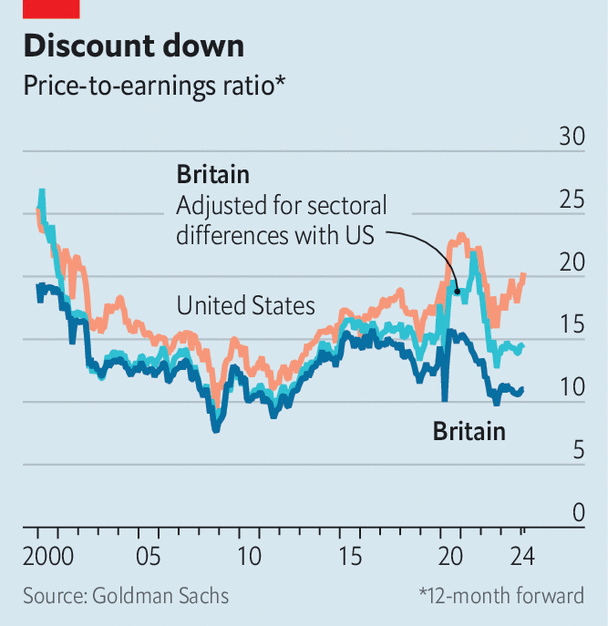

That valuations are low on British equities because there isn’t a stable base of domestic buyers. The mechanics of that have always felt a bit hand-wavy to me6. More significantly, it fails a basic timing sense-check. In public markets, British equity valuations started lagging those in the US from the mid-2010s onward. But the big upswing in foreign ownership started far earlier in the 1990s and was done by 2010 or so. If foreign ownership was a problem for valuation, why were valuations well-behaved throughout the period where foreigners were taking over the market?

Regardless, until 2022 or so, the UK-US valuation gap was mainly explicable by the fact that British equities had less exposure to tech, the big growth success story of the 2010s/2020s, relative to US equities. You can also get a good way towards explaining the wider post-2022 discount as: (a) a lingering post-Truss hangover, and (b) the fact that UK-listed tech has far fewer AI beneficiaries than US-listed tech.

That having a foreign investor base inevitably means that companies move more of their operations overseas. You hear this most on start-ups, where Britain does have a real lack of domestic scale-up capital. Frankly, I’m not totally unsympathetic to this argument—you can probably imagine scenarios where there is some path-dependency in founders wanting to be closer to investors, and that influencing where the headquarters end up.

But I’m not sold that the effect of investor location specifically, as opposed to the broader appeal of the American market (larger than Britain’s, and with businesses anecdotally more willing experiment with software), is huge. Nor does it feel realistic, even if a very large share of British pension assets were pushed by mandation into UK VC, that the majority of investors in many start-ups and scale-ups wouldn’t be foreign, and probably American.

Anyway, presuming that businesses are guided mainly by business imperatives (and not the geography of their investors) in deciding where to move their operations still strikes me as a broadly reasonable baseline.

That having non-Brits profit off “British success stories” is a problem. You hear this a lot, even though the logic is pretty spurious. Two obvious issues:

What really matters for economic growth is that productive activity is happening in Britain, not who funds it.

This claim neglects the counterfactual: if Brits have instead invested elsewhere, and done so because that option had the highest expected return, then Britain is hardly the loser in that interaction.

Besides, there are better places to start if your concern is revitalising British capital markets. One I’d flag, which probably should be discussed more often, is stamp duty on shares, a 0.5% financial transaction tax. Unlike much of this pensions business, there is fairly persuasive evidence that this tax depresses the prices of UK-listed equities.7

Premise 3: Those effects are more important than higher returns

Let’s say you are persuaded by some of those arguments though, or other similar ones. The next question is how large the effect sizes of a policy of mandation actually are. If you believe markets are even moderately efficient (and so most investment opportunities are already getting funded, if just marginally less cheaply), then it’s tough to see them as all that large.

Meanwhile, the impact on the wealth of British pension-savers of a worse-constructed portfolio could easily be material. Here’s what I wrote on this in a piece for The Economist in March 2024, which also raises some of the same arguments I make here:

“For British investors, patriotism is costly. Sticking money in domestically listed equities over the past decade has meant total shareholder returns two-thirds lower than investing in a global index that strips out Britain. It should be no great surprise, then, that British investors exhibit less “home bias”, an over-allocation to domestic equities, than most rich-world peers (see chart). A decent financial adviser would call this shrewd.”

The benefits of a better-funded pension system are huge. Pressure to constantly raise the state pension goes down. Households are better insulated from shocks. Those, to my mind, almost certainly outweigh even the best-case-scenario for mandation, which might at best reduce the cost of capital slightly for some British firms.

An unexpected resonance

I didn’t write about the pension issue for The Economist last week, in part since I’d rehearsed a lot of the main arguments in previous articles.

Instead, I wrote about a bizarre and slightly terrifying provision in Donald Trump’s tax bill. That, too, sought to use the power of the state to keep cash from moving freely across borders.

However uncharitable I am about what the British government is up to, though, this is incomparably madder.

“Section 899 would add a 5% tax surcharge in its first year, and another 5% each year after that to a maximum of 20%. That higher rate would target dividend, interest and property income flowing abroad. For now, the language in the bill leaves open a few possible gaps, but punitive rates would almost certainly hit any lending in America by banks from offending countries, dividends on American stocks for those countries’ investors and profits sent home from American subsidiaries. Sovereign wealth funds and public pension funds linked to governments that fall afoul of the Section 899 regime would also lose their existing tax exemptions. Altogether, the move amounts to a radical act of tax protectionism, a near-unprecedented plan to use America’s tax code as a cudgel to knock other countries into line.”

Conveniently, plenty of “world ex-UK” ETFs exist for this purpose. I actually don’t follow this advice with my own investments, but that’s largely for sentimental reasons—someone has to back Britain. (“Back” here in the narrow sense of not explicitly underweighting…)

UK-listed equities are actually unusually likely to be predominantly foreign businesses, especially in the FTSE100, so this logic applies a little less strongly in Britain than elsewhere. But it still holds.

Property is a bit fiddly, since people also have an implicit short position in housing by virtue of needing to live somewhere.

And may actually outperform when the pound falls, if they aren’t FX hedged.

I don’t dwell here on the focus on private assets, but I do also have some real worries about the government over-stating the diversification benefits of PE/VC/infrastructure etc, and over-extrapolating returns based on a multi-decade lookback window that includes a period before those were mature asset classes—when there was more low-hanging-fruit return to be had from financialising them. Cliff Asness covers the diversification question well in his writeups about “vol laundering”.

“Reflexivity” is not a sufficient answer!

The IFS paper that I link looks at cases where there was news about the stamp duty reserve tax rate changing, and how much equity prices moved.

As an American transplant, I found the British obsession with property as store of wealth puzzling, different from the US where wealth lies stocks and shares. Until I saw the the tax system bias to property over equities, and the planning act (as you mentioned).

No CGT on primary homes means we can shovel unlimited savings into primary home ladder climbing - unlike ISA's £20K cap - and make 20:1 leveraged bets confident that the planning act will help you prop up the price and you will almost never go under water. You can NIMBY all new competing supply to skew the housing market in your favour. Or charge eye-watering rents to the younger generations.

Any proposal - from a studio to movie studios - is fought to the death as possibly impacting house value; never mind having a major studio near your house may drive up the house' value as people who work there might want to live nearby.

CGT exemption needs to be capped (like US does).

"The government’s thinking on the housing crisis seems to have moved backward"

This infuriates me. Removing barriers to growing housing supply side is an almost no fiscal cost growth lever she can pull but doesn’t.

They have talked a good game on housing and fiddled around the edges – setting higher targets for councils. These are all slow burn and long-term.

Houses aren’t affordable, we have gone from house price/income 4:1 to 10:1 and eye-watering rents. We need radical action to get the supply side going quickly. I’d gut the Planning Act and start all over again.

No more vetoes to current home-owners on new builds/ conversions unless there is an absolutely compelling reason such as the skyscraper next door will block all my sunlight access. No more councils wasting time and money on applications to paint their front door a certain colour (mine does in some areas).

Default to yes and set a clock. Don’t let the NIMBYs delay for years. My local NW London suburb pensioners association fights any building over 2 floors with the argument “we can see the floors and hence they are detrimental”.

Hire Jeremy Clarkson as chief marketing officer for their plans, he knows all about council meddling.

Labour has a stonking majority. Cost of living crisis related to housing is hammering their core younger vote. The NIMBYs and older pensioners vote Tory and Lib Dem anyways. What does Labour have to lose? Be bold.

It surprises me how the left tends to bend over backwards to accommodate their non-voters, who then take the win and vote right anyways. When the right wins, it’s all about screwing the left and boasting about it. Biden sent billions in subsidizes to red states and got no credit. The Republicans voted against that but then took credit for money into their states and districts.

Why is Labour persisting with triple-lock? The winter fuel payment U-turn was just shoveling more money to the richest segments of the population.